THE HEART OF DAYTONA

WINNING ISN'T EVERYTHING

SCOTT GRAY

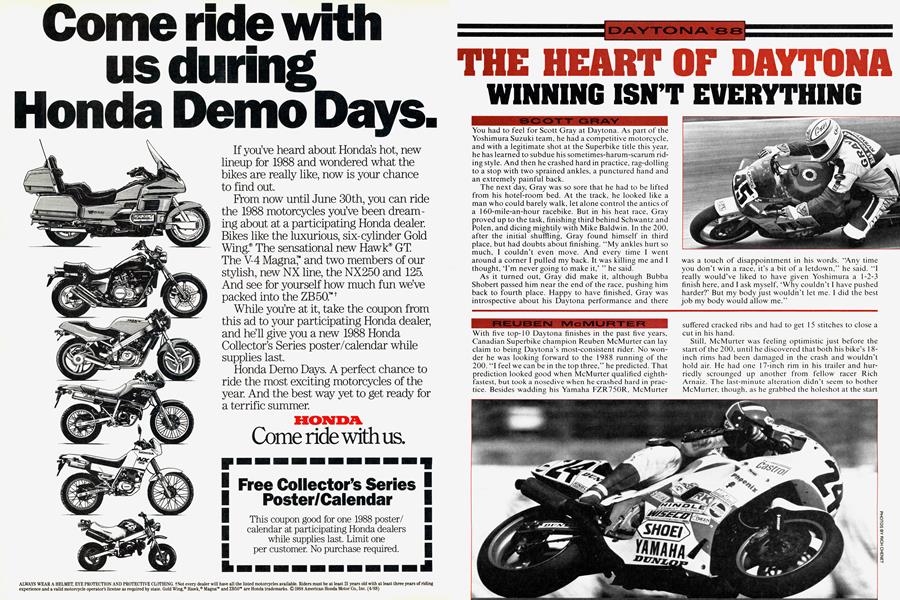

You had to feel for Scott Gray at Daytona. As part of the Yoshimura Suzuki team, he had a competitive motorcycle, and with a legitimate shot at the Superbike title this year, he has learned to subdue his sometimes-harum-scarum riding style. And then he crashed hard in practice, rag-dolling to a stop with two sprained ankles, a punctured hand and an extremely painful back.

The next day, Gray was so sore that he had to be lifted from his hotel-room bed. At the track, he looked like a man who could barely walk, let alone control the antics of a 160-mile-an-hour racebike. But in his heat race, Gray proved up to the task, finishing third behind Schwantz and Polen, and dicing mightily with Mike Baldwin. In the 200, after the initial shuffling, Gray found himself in third place, but had doubts about finishing. “My ankles hurt so much, I couldn’t even move. And every time I went around a corner I pulled my back. It was killing me and I thought, ‘I’m never going to make it,’ ” he said.

As it turned out, Gray did make it, although Bubba Shobert passed him near the end of the race, pushing him back to fourth place. Happy to have finished, Gray was introspective about his Daytona performance and there was a touch of disappointment in his words. “Any time you don’t win a race, it’s a bit of a letdown,” he said. “I really would’ve liked to have given Yoshimura a 1-2-3 finish here, and I ask myself, ‘Why couldn’t I have pushed harder?’ But my body just wouldn’t let me. I did the best job my body would allow me.”

REUBEN McMURTER

With five top-10 Daytona finishes in the past five years, Canadian Superbike champion Reuben McMurter can lay claim to being Daytona’s most-consistent rider. No wonder he was looking forward to the 1988 running of the 200. “I feel we can be in the top three,” he predicted. That prediction looked good when McMurter qualified eighthfastest, but took a nosedive when he crashed hard in practice. Besides wadding his Yamaha FZR750R, McMurter suffered cracked ribs and had to get 1 5 stitches to close a cut in his hand.

Still, McMurter was feeling optimistic just before the start of the 200, until he discovered that both his bike’s 18inch rims had been damaged in the crash and wouldn’t hold air. He had one 17-inch rim in his trailer and hurriedly scrounged up another from fellow racer Rich Arnaiz. The last-minute alteration didn’t seem to bother McMurter, though, as he grabbed the holeshot at the start of the race. Schwantz took over before the end of the first lap. but McMurter rode well, avoided trouble and at the end finished fifth, beaten only by a trio of factory-backed Suzukis and a semi-works Honda.

MIKE BALDWIN

How quickly some things change. Last year, Mike Baldwin was Randy Mamola’s partner on Kenny Roberts’ Lucky Strike Yamaha team, and had every hope of bettering his fourth-place finish in the 1986 500cc World Championship. But a mid-season crash put him out of the running at the GPs and left him with a slowly recovering right hand.

This year, at Daytona, Baldwin started his comeback. But instead of being on a heavily sponsored works team, he had to do it as a privateer, riding a Honda VFR750 tuned by George Vincensi, the proprietor of G-V Performance.

The week started well, with Baldwin setting seventhfastest qualifying time. “I think the bike is capable of winning,” he said optimistically. And in his heat race, Baldwin looked every bit the top-ranked GP rider, leading the race early on, and dicing with Schwantz, Polen and Gray. But that ended on the fifth lap when, braking from over 160 miles an hour into Turn One, Baldwin locked his Honda’s front wheel, and slid and tumbled to a sickening stop. His VFR was destroyed, and Baldwin was bruised and left with deep abrasions on his left elbow and forearm.

Vincensi spent two days patching the VFR, getting it ready just in time for the 200. Baldwin started strongly, but a fuel-starvation problem appeared when the gas level dropped by two gallons or so, and eventually led to the bike being parked. Baldwin’s comeback would have to wait for another day.

YUKIYA OSHIMA

Japanese national FI champion Yukiya Oshima speaks little English, but he made it clear that while racing at Daytona is essential for his career and development, it is also very risky. “In the U.S., you have a wide spread of rider talent and experience on the track,” he said, “that makes it difficult for the faster riders. Because of stricter licensing in Japan, the competition is much closer.”

But taking chances on a track full of slower, less-talented riders is necessary because of the experience a rider can get from just one week at Daytona. Fujio Yoshimura, Ohsima’s team manager, says that Daytona forced Oshima to be more precise in his acceleration and braking because the track is more slippery than those in Japan. Even though Oshima qualified fourth fastest, he could have used a little more practice on the slippery surface; he pressed hard in the initial stages of the race, even holding the lead for one lap, but he crashed in Turn One when he lost the front end, remounting to finish in 45th place.

LARRY SHORTS

Larry Shorts had a tough week. Shorts, two-time AMA National Endurance co-champion, crashed a Ninja 1000 in an endurance race one week before the 200, trashing the bike and giving himself several bumps, bruises and scrapes. During Cycle Week itself, he fared a little better, finally getting his Rob Muzzy-prepared Ninja 750 qualified in the 25th position. Unfortunately, Shorts crashed hard on the second lap of the 200, demolishing the bike.

Shorts’ Ninja was one of five privateer Kawasakis on the Daytona starting grid this year. All were little more than production bikes, and Shorts’, the fastest of the Ninjas, was down almost eight miles an hour per lap on the lead ers. Shorts gets no official help from Kawasaki, but he hopes that if he wins a couple of races, the factory will get

excited by his effort. Even if that doesn't happen. he likes being on the underdog Ninja. "If you do goodS" he says. "it always makes you look better."

RANDY RENFROW

Randy Renfrew and Vance & Hines are a matched pair: a rider and team still coming to terms with Superbike racing, and both committed to eventually being on the top. Renfrew is known as a Formula-bike specialist, winning the 1986 Formula 1 championship on a Honda RS500 two-stroke Triple, and capturing the 1983 250cc championship, as well. But on a Superbike, his extreme hang-off style has often looked awkward, and he hasn’t wound up at the front of many races. And while Vance & Hines are drag-racing overdogs, their roadracing attempts haven’t exactly left the competition quaking in their boots.

This year, both rider and team hope to change those images. Renfrew is riding nothing but the Vance & Hines Superbike, forsaking the 250cc class. And Vance & Hines are committed to improving their motorcycle. Renfrew notes, "It’s hard to stay pysched when you’re trying to qualify in 10th spot and you’re used to trying for the pole, but you just have to keep trying." Renfrew, through steady riding, was able to turn that 10th place on the starting grid into an eighth-place finish in this year’s Daytona 200.

Both he and his team are looking for better results later. Vance & Hines will soon replace their 1987 GSX-R Superbike with a 1988 model, and Renfrew is already excited. Why? Renfrew has sampled the new bike, and says, "It steers quick and light," just like the Formula bikes he knows so well. If he adapts to it the way he did to the Honda RS500, the Superbike front-runners will have an additional rider to contend with.

ANDERS ANDERSSON

Nineteen eighty-eight was Anders Andersson's third Day tona, and it looked to be his best. The Swedish national Superbike champion and test rider for the Ohlins suspen sion company said, "I like Daytona, and with experience it's getting easier. The first year it was a real problem figur ing out the track—and getting thrown out of the garages at night. Fast year it was better: We even left before the 7 p.m. curfew some nights. This year it’s going very smooth and easy.’’

Smooth was the operative word, as Andersson’s GSX-R carried him to a second-place finish in his heat race, and a spot in the Camel Challenge. In the 200. Andersson ran in fourth place for the first half of the race, just in front of eventual fifth-place finisher Rueben McMurter. But then the easiness ended with a blown motor, leaving Andersson’s Daytona hopes on hold until next year's race.

DOUG CHANDLER

Privateer Honda rider Doug Chandler qualified 10th, but otherwise had a disappointing Daytona. In his heat race, he was challenging for second place when his engine blew up. On race day, with his backup engine, he ran with the first group of riders chasing the leaders, and by the ninth lap had worked up to fifth position. But while pursuing Scott Gray for fourth, Chandler ran into difficulty. “I was catching him, but then I hit a slick spot on the exit of the Chicane,” said Chandler. He went down and broke a small bone in his right foot. In addition to suffering the pain in

his foot. Chandler had to listen to the engine in his crashed VFR run wide-open until it blew up. As for the rest of the season, Chandler said, “We’ve got competitive bikes—if we can keep them running.”

GARY GOODFELLOW

Gary Goodfellow spoke for a lot of racers at Daytona when he said, “Hey, everyone here has a hard-luck story to tell.” For Goodfellow, former New Zealand motocross champion and now a resident of Canada, the hard luck began late last year in a start-line crash that left him in intensive care for four days with all his ribs broken, a broken leg and a broken shoulder blade. Daytona was Goodfellow’s first race since the accident, and he had a hard time lining up sponsorhip. With only two weeks left before the race, he was shipped a Suzuki by a Japanese clothing company. Unfortunately, Goodfellow had to pay the freight costs. By the time he and the bike arrived in Florida, Goodfellow was already $ 10,000 out of pocket.

The money seemed to be well-spent when Goodfellow finished third in his heat race, qualifying for the Camel Challenge and bolstering his confidence. “If everything goes right, I can win it just as easy as anyone,” he said. A few laps into the 200, though, Goodfellow’s run of hard luck resurfaced as his engine started acting up, eventually forcing him to retire. But the 32-year-old Goodfellow wasn’t at all downcast in the pits after the race. “I’ll be back,” he said. “I’ve spent a lot of time and effort and money trying to do this (roadracing) right, and I’m not ready to stop now.”

JOHN ASHMEAD

No one could say that John Ashmead’s Honda VFR wasn’t fast enough; its HRC-built powerplant propelled it through Daytona’s speed traps at 168 miles per hour, just one mile per hour down on Bubba Shobert’s Honda. That speed, and Ashmead’s talent, had the bike running hard in the 200, challenging for the fourth spot with just seven laps to go. “I was in fifth or sixth place and had Reuben (McMurter) in my sights when the engine seized,” said Ashmead. He managed to get the bike restarted, but it stopped running again almost immediately, ending his Daytona 200. That’s a bitter way to end any race, but Ashmead found some consolation just in competing at Daytona. "For a race that drives you crazy all week," he said, "it's one of the funnest of the year."

David Edwards

Camron E. Bussard

Steve Anderson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialDown But Not Out

June 1988 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeMoto-Immortality

June 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsAlas, Albion

June 1988 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1988 -

Rondup

RondupIs There A Ring-Ding In Your Future?

June 1988 By Steve Anderson -

Rondup

RondupLetter From Japan

June 1988 By Kengo Yagawa