Alas, Albion

LEANINGS

I WOKE UP IN THE NIGHT FEELING UNeasy, half dreaming something in the house was wrong. It was an odor. The human nose has a way of sending wake-up calls to the brain, probably dating back to the cave man's fear and loathing of wolf breath, and mine had phoned a message that something was not quite right.

I sat up in bed and sniffed the air, confused for a moment. Then I relaxed. It was only the Triumph.

Ah, the British.

The aroma that filled our house had its source in the garage, but had somehow found its way to the bedroom through a 5-by-7-inch cat door, across an entire dining room and down a long hallway to the exact opposite corner of the house. Still, there was no mistaking it for anything other than the distinctive fragrance of leaded gasoline leaking past the float-bowl gasket of an Amal Monobloc carburetor, and from there dripping its way onto the engine cases beneath, like slow Chinese water torture. Even in the dark, I could picture the entire process.

It wasn’t merely the smell of raw gasoline. It was a special English smell you get when a perfectly controlled rate of eternal seepage allows gasoline to half-evaporate before it drips, leaving a thick, red deposit of lead and heavy mineral spirits on the underside of a carb body, along with a smell so pungent you suspect that fossil fuel might be reverting to its original state of primordial soup in a warm tropical sea. There are other elements in the aroma, of course, like mildly decayed, cotton-insulated wiring, old foam beneath the vinyl seatcover, and motor oil heated and chilled a hundred times on the outside of the engine; but the main ingredient, I think, is still gasoline, or whatever remains when the volatile ghost of gasoline has left the scene.

Like a farmer who feels compelled to get up and see why the dogs are barking, I heaved myself out of bed to go check the Triumph, just to make sure I hadn’t left a petcock open, flooding the garage floor with fuel. I got dressed and shuffled out to the garage to have a look.

No major leaks or oil spills, just the usual seeps. A warm spring wind was blowing against the garage door, no doubt wafting the smell into our house with more force than usual. I ran my finger along the underside of the Amal, and there was the usual residue, oozing thickly red. Despite my best efforts.

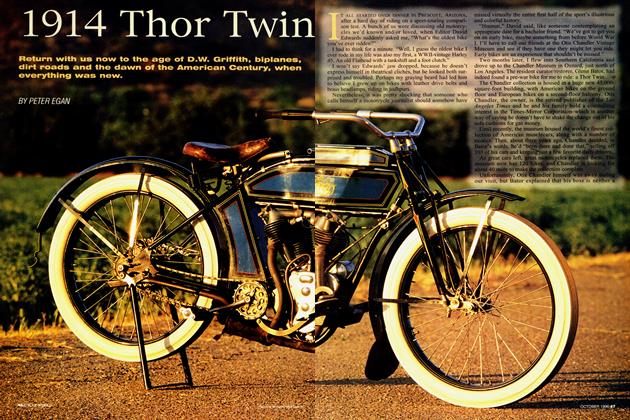

The float-bowl sidecover had been leaking badly when I bought the Triumph, so my first action on the bike’s behalf had been an attempted repair. The carburetor had been designed to leak, of course; nobody but a child, inexperienced in the ways of the world, would seriously believe that a flat metal plate, a paper gasket and three screws would hold back a reservoir full of a sneaky, low-viscosity fluid like gasoline for long, especially if the carburetor were rigidly attached to a hot, vibratory, 650cc vertical-Twin motorcycle engine.

“Use two gaskets,’’ my friend Bill Getty at British Parts Old & New had told me. “That usually cures the problem.’’

So, I’d put on two gaskets, after carefully checking the plate for flatness and filing down the small, raised volcanoes around the screw holes where the metal had pulled through. It still leaked. Next, I would try various glues and gasket cements from my large drawer of same. Sooner or later, I’d find a solution.

What was needed, of course, was a rubber O-ring. Not only a rubber Oring, but a float bowl designed like a cup rather than a bass drum, allowing the bowl to have its sealing surface above the fuel line. Like the one on my ’82 Honda XL500, which sat nearby. (Triumph later switched to a concentric Amal with real float bowls that didn’t leak as much, except when you deliberately made them overflow by using the starting ticklers.)

What was it, I wondered, that so mystified and eluded British engineers when it came to the design of gaskets, seals and mated surfaces. They never did get the idea, right up until the end, that fluids belong on the inside of an engine, while fresh air and sunshine belong on the outside, and that there is seldom any real advantage in having these disparate elements swap sides, except in the case of combustion gases.

All of the British bikes and cars I’d owned had leaked one or more fluids from some orifice (I’d never owned a British airplane, but Spitfire pilots tell us in their memoirs that the smell of hot, leaking glycol from that big, water-cooled Merlin is one of their most pungent memories of flight). Old road tests I’d seen in English publications had actually suggested that oil leakage was a desirable trait in motorcycles and cars because it preserved their lower extremities from rust.

Leakage is so universal in these machines, it has now become part of the lore and romance of Owning British; and half the fun of restoring an old Triumph, Norton or BSA lies in reducing fluid loss to a minimum through careful assembly, subtle filework, double gaskets, aftermarket sealants and right thinking.

Still, as I sat in the garage and looked at the Triumph, I couldn’t help wondering where the British motorcycle industry would be today if they had discovered O-rings, precision surfacing and horizontally split engine cases. Some people simply won’t forgive a motorcycle that wakes them up in the night. Others of us are willing to overlook a little nighttime seepage—provided the bike doesn’t put us to sleep during the daytime.

Peter Egan

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialDown But Not Out

June 1988 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeMoto-Immortality

June 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1988 -

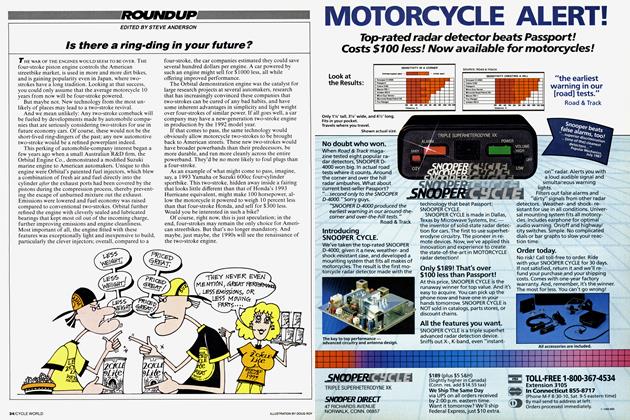

Rondup

RondupIs There A Ring-Ding In Your Future?

June 1988 By Steve Anderson -

Rondup

RondupLetter From Japan

June 1988 By Kengo Yagawa -

Rondup

RondupLetter From Europe

June 1988 By Alan Cathcart