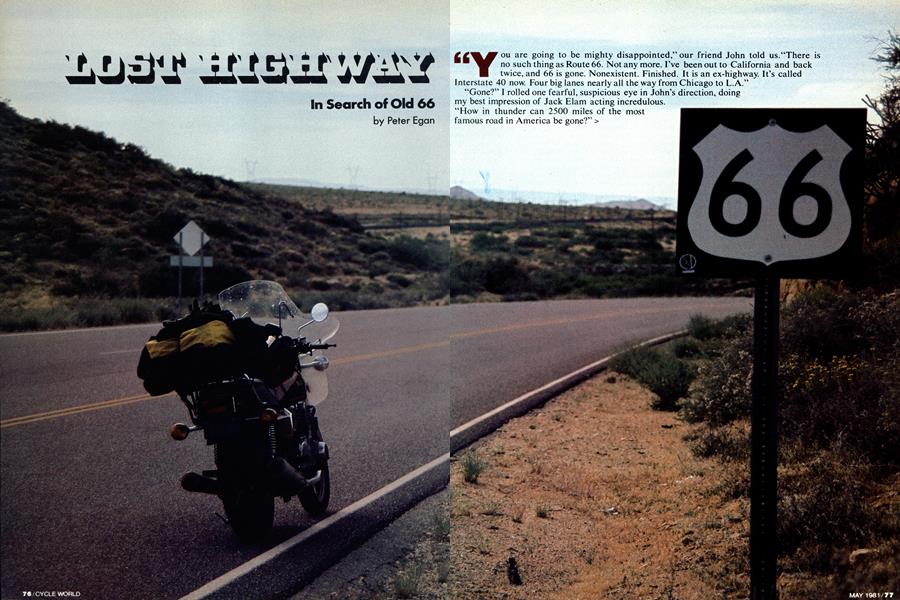

LOST HIGHWAY

In Search of Old 66

Peter Egan

"You are going to be mighty disappointed,” our friend John told us.“There is no such thing as Route 66. Not any more. I’ve been out to California and back twice, and 66 is gone. Nonexistent. Finished. It is an ex-highway. It’s called Interstate 40 now. Four big lanes nearly all the way from Chicago to L.A.” “Gone?” I rolled one fearful, suspicious eye in John’s direction, doing my best impression of Jack Elam acting incredulous. “How in thunder can 2500 miles of the most famous road in America be gone?” > “Okay. Maybe there are still a couple of places in Arizona or New Mexico where 1-40 bypasses part of the old road, but the rest is pretty much paved over.”

I was stunned. Route 66 gone? Paved over and renamed? It was like planning a raft trip down the Mississippi and being told the river was all dried up. Nothing but a dusty riverbed full of catfish skeletons and old tires. Impossible. I’d wanted to take a motorcycle trip out Route 66 to California ever since my budding passion for bikes had collided head-on with a TV program named after the highway. Two guys named Todd and Buzz started it all.

They appeared one evening two decades ago on the black and white snowstorm of my parents’ 12-inch TV screen. It was a new program with an unusual premise. It seemed these two single guys had bought a Corvette and set out to work their way across the country. They were searching for something but didn’t know what. Every time they cruised into some dusty little town they found jobs driving forklifts at the plant or erecting oil rigs. They inevitably got tangled up with some menacing local types who were dragging their knuckles around and looking for trouble, and usually there was a wistful young (but aging fast) woman who worked at the diner, waiting for someone to take her away from it all. In the end Todd and Buzz always left town a little wiser but still searching, alone in their Corvette on Route 66.

Stirling Siliphant wrote most of the fine, hard-hitting scripts, and the music by Nelson Riddle had a jazzy, spirit of the open road kind of sound. The Corvette, the lost women, the music, the freedom . . . it was a heady combination to a 12year-old who was, at any given moment, in hot water with his parents for not raking the lawn or painting the other half of the garage door.

A few years later, when I got so I could read without moving my lips, I discovered John Steinbeck and read The Grapes of Wrath. This story traced the misadventures of the Joad family, a clan of dust bowl farmers, from their ruined Oklahoma homestead to a supposedly better life in California. They suffered every setback a long journey can dish out to folks without enough money. Route 66 in the 1930s was the setting, and Steinbeck described the two-lane road and its towns, car lots and roadside camps so well the Joad family and the highway itself became American institutions.

By 1965 I’d become an R & B fan, listening to Chuck Berry and the Rolling Stones belt out their own versions of Bobby Troup’s much recorded song, Route 66. “Well it winds from Chicago to L.A., more than two thousand miles all the way . . . well get your kicks on Route Sixty Six . . .” That was enough for me. I’d seen the TV program, read the book, and now my record player was driving the message home. It was clear no self-respecting person could call himself an American if he hadn’t checked out this fabled highway. Route 66, the pipeline to California, path to the Promised Land, was a fixture in the American consciousness as surely as the Mississippi River, the Natchez Trace, Pennsylvania Avenue, Main Street and Sunset Strip.

It was the kind of trip, sooner or later, you have to make. Especially if you are a motorcyclist and always looking for a good reason to travel. Or in my case even a fairly mediocre reason of practically no discernable consequence or socially redeeming value.

The opportunity came last summer. Editor Girdler dispatched a Suzuki GS1000 to cover the Winston Pro races at Elkhart Lake in my home state of Wisconsin and asked if I would ride the bike. My wife, Barbara, could go along for the ride. The plan was this: Take the most direct northerly Interstate east, making all due speed with a Gypsy Scout radar detector scanning for cops; cover the races and then make a more leisurely return trip on Route 66.

Borrowing from our stock of items to evaluate we outfitted the GS with a Silhouette Fairing, a Lockhart luggage rack, a clip-on Tourmaster rack bag, my old Eclipse tank bag, and a nice set of low Superbike bars I carry around and bolt on to every bike I ride. The GS1000, with 3000 mi. on the odometer, got an oil change and plugs. We made it to Wisconsin in three days on the Interstate and got one speeding ticket, $50 worth, at a speed trap near Denver. It was a visual speed trap—no radar — where they time your progress between two stationary objects. They said we were making too much progress.

There was no noise,just the wind through the trees,and it was somehow ghostly; the busiest road in America recently gone silent.^4

We averaged 85 mph for the trip. The radar detector saved us from at least a dozen other tickets in Iowa alone, which was literally crawling with police, all throwing out enough radar beams to fry an egg or raise your voice one octave. The GS 1000 got 40 mpg and used one quart of oil and a small can of chain lube.

It was in Madison, Wisconsin, after the Elkhart races that our old friend John Oakey cast his rather large, hulking shadow on our return trip. “Dull,” he pronounced. “Nothing but freeway and desert. I don’t envy you.”

The map indeed showed only a few small portions of road marked US 66. There were a few miles in Oklahoma parallel to 1-40 west of Tulsa; a patch of incomplete I-road near Tucumcari, and a stretch that followed the Rio Grande south of Albuquerque. Arizona was most promising, with a big northern loop of old 66 bypassing the freeway from Ash Fork to Kingman.

There had to be more; maybe some small traces of the old road going through the small towns. There must be old motels, gas stations and restaurants still intact near the four-lane. It couldn’t all be torn down, hauled away and gone. America covers its architectural tracks fast, but not that fast. The time was clearly ripe for another of those field trips in Contemporary Archaeology and the Study of Modern Antiquities, those same quasi-academic disciplines that search out and preserve Gene Vincent albums, 1959 Cadillac Coupes de Ville, unfiltered Camels and juke boxes that look like neon cathedrals.

We left Madison on a blistering hot Wednesday morning in June and headed down Highway 51 to pick up 1-55 (aka US 66) at Bloomington, 111. We hit the Interstate just in time to join an accordion of cars following a black and white sedan from the Illinois State Patrol at 55 mph. Exactly 55 mph. We shifted down a gear and waited. There’s something fairly pathetic about 10 or 20 adults backed up and crawling along in orderly procession behind a squad car. It reminds me of following my fourth grade teacher down the street on a class trip to the fire station. The patrol car finally eased itself down an exit ramp and the tail pipe of every trailing car coughed out a sigh of relief and picked up speed. Barb and I rolled up to 65 mph, or about half speed for the Suzuki.

Route 66 caught us by surprise. We had mistakenly counted on the state map, which was reasonably detailed, to show any remaining sections of the old highway. There were none on the map, and 1-55 travels nearly straight and level across Illinois, so we assumed the new road had been laid down over the old. Not so.

Just north of McLean, Illinois, Barb gave me a jab in the ribs and pointed to our right. There, cutting a narrow concrete swathe across meadows, through clumps of trees and across creeks on small bridges was an abandoned highway with tufts of grass growing between the slabs of patched pavement. It was clearly the one and only original Route 66 of song, novel and television. One look and you knew it was the real thing.

We got ofif at the next exit and found a spot where the old highway crossed a county road. The intersection was unmarked; no stop signs, no manicured apron at the corner, no signs of any kind to say what the highway was; 66 was a Highway With No Name. You had to drop dowm over a low dirt shoulder from the country road even to get on it. The highway was just there; nameless and heading off inviting and empty through the rural countryside. We shut off the bike, removed our helmets and sat for a few minutes looking down the road. There was no noise, just the wind through the trees, and it was somehow' ghostly; the busiest road in America recently gone silent. You could almost hear the fading echo of a 327 Corvette rumbling off into the distance.

We put on our helmets and headed southwest.

The old road was in remarkably good shape despite weeds, grass, wild oats and the occasional sapling growing up through the seams. The concrete slabs were solid, showed little weather damage and were in relatively good alignment. The road was made from thousands of squares of white concrete laid end to end and joined with small strips of black tar. In a few' places the broken white and solid yellow lines were still visable, but most of the paint was weathered away.

We started cruising tentatively, watching for chuckholes and broken glass, but soon found the road clean and smooth enough for normal speeds. After twenty minutes we were cruising at 70 or 75 mph, or anything we felt like. The highway was like a science fiction dream; a scene from one of those post-nuclear novels where a few people find themselves alone on an empty Earth; a road of your own, a fast motorcycle and nothing to slow you down.

Almost nothing. True to the Last Inhabitant fantasy, the only risk came from animals. Conditioned to an unused road, they’d grown bold around the pavement, living, hunting and nesting and generally carrying on as animals will in the long grass beside the highway. The dipping, erratic flight of roadside blackbirds had Barb gripping my sides as they narrowly missed our windscreen. Rabbits, chipmunks, strolling pheasants and something that looked vaguely like a mud hen were all stirred up by the passing commotion of our big Suzuki. Uncomfortable with my sudden role as bull in Nature’s own china shop and general despoiler of woodland tranquility I backed off on the throttle.

None too soon either. We crested a rise and I clamped on the brakes. The highway had ended. The road was cut ofif by a black and white striped barrier and then disappeared under the soil of a cornfield. Ahead was a high embankment formed by an exit ramp from the nearby I-road. Short of jumping the barrier and plowing corn for 50 yards with the Suzuki, there was nothing to be done. We turned reluctantly around and backtracked for five miles to the last entrance ramp, climbed onto the Interstate, returned five miles and took the very exit ramp that had blocked our path. On the other side of the cloverleaf we were able to dirt track our way onto old 66 again.

It was a road in a hurry that paralleled the railroad tracks and didn’t ump you off in every burg and speed trap.

The scene was repeated over and over again. Route 66 ran roughly parallel to 1-55, and each time 1-55 threw off an exit ramp 66 ended. Sometimes you could play dirt bike, go around the barrier and cross the exit ramp to the other side, where 66 resumed; sometimes there was a dirt road detour off the old highway, especially near small towns, so you could circle around the exit; and sometimes, most of the time, you just had to go back five or 10 miles and get on the Interstate. A dirt bike with knobbies and a pair of wire cutters might have helped, but not always. Particularly in one spot, where a washed out bridge had been left washed out.

At every chance we left the freeway and traveled down the boxed-in sections of old 66, genuinely resenting having to mingle with the vacationing boat-town masses on the four-lane. Sixty-Six was never very far from the Interstate, but close enough to farms, houses and trees that it could be said to go through the country rather than over it. Its curves and hills followed the topography of the land and the roadcuts were small. The bridges, smaller and more elegant, were built as overhead trestles or as reinforced concrete spans, many with the decorative cement work and craftsmanship lost on public works since the days of the WPA. Depression bridges were best.

We had hoped 66 would take us through a lot of small towns, but found we couldn’t count on it. Even back in the old days 66 was a fast road. It went past a lot of towns rather than through them, affording only a passing, sidelong glance down the main streets of small farm communities on the roadside. You could go into the towns but you had to want to. It was a road in a hurry that paralleled the railroad tracks and didn’t dump you off in every burg and speed trap from Chicago to L.A. Which is why our highway ended so often at exit ramps instead of taking us into town.

An exception was McLean, Illinois, where 66 brought us right up to the front door of the Dixie Trucker's Home, a truck stop and restaurant recommended in Road Food. Road Food is a guide book that lists and describes eating spots deemed worthy of the cross-country traveler’s patronage. It said the Dixie Trucker’s Home had, among other things, good fried chicken. The truck stop was crowded and busy, one of those gleaming clean places where you could eat off the floor, as my grandmother used to say, but they had plenty of tables and plates and we didn’t have to. The chicken was very good.

We followed 66 wherever possible through the afternoon and rode into a warm, soft summer evening in Lincoln. It was just sundown and baseball diamond lights came on brilliantly as we passed the city park. A drive-in theater along the highway began its show and we caught a glimpse of the wordless previews to The Long Riders; much noiseless shooting, smoke and commotion going on. We decided to press on a few hours longer to Springfield. After a hot day the merely warm evening felt so good we hated to give it up.

After a five mile stretch of old 66 and another sudden dead end, we chose to ride on 1-55. The strain of watching for barriers, broken glass and red animal eyes on the deserted highway took too much concentration at the end of a 500-mi. day. We stopped for the night in Springfield, Lincoln’s home town, at one of those budget (read cheap) motels with a dollar figure in its name, of which inflation has now made a mockery. The sign out front advertised “Good Rest, Sweet Dreams,” a seductive promise. The rooms, balconies and restaurant upholstry were mostly turquoise and orange, colors that somehow came to denote modernness in the late Fifties. The painted cement block construction and the colored steel balcony panels with traces of rust gave the place the subtle flavor of a post-war barracks for officers in the New Army. We had good rest, but in the morning could recall no dreams.

We stayed on 66 all the way into St. Louis the next day, where the highway lost its identity somewhere in a maze of cloverleaf bridges and we found ourselves in a minor manufacturing district near the old Cahokia Indian Mounds. We got back on 1-55 and crossed the Mississippi, past the big arch that is the Gateway to the West. The arch glinted golden in the noon sun. “I'm suddenly hungry for a hamburger,” Barb remarked.

We stopped at a truck stop in St. Louis, a glaring, barren place with bright fluorescent lights. I had a perfectly square block of hash browns and a perfectly round hamburger dwarfed inside a perfectly round bun. A perfect meal.

In the beautiful rugged hill country west of St. Louis Route 66 suddenly reappeared beside the main road, curving in and out of the woods and climbing hills beside the (now) 1-44 roadcuts. It looked too inviting to wait for the next exit, so we just pulled off the Interstate and wallowed the big Suzuki down a rain gully and launched ourselves up onto the timescarred pavement of 66 again.

Near Stanton, Missouri, we swept down through a wooded glen, rounded a hairpin turn at the bottom and crested the next hill to find an amazing collection of old motels, all abandoned except for the Ozark Courts, where the restaurant had been turned into a home. We stopped to take a look around and a nicely dressed woman and her daughter came out from behind the motel to talk to us. The woman said she and her husband ran the restaurant for 10 years before the highway came through in 1963. The motel closed, as did the others nearby, and the restaurant went broke. Her husband, she explained, now works at a MacDonald’s in Stanton.

“The place was really jumping back then, before they built 1-44. We were open 24 hours a day and the counter was always full. There was a bad stretch of road near here, though.” She pointed east down the road. “That curvy section you just came through, where it goes downhill through the trees, that place caused a lot of accidents. People would cross the yellow line and hit head-on. Seems like there was an accident nearly every other night, especially when it got foggy down there. Must have been twenty, thirty people killed there over the years.” She brushed a strand of hair out of her eyes and pointed to the traffic droning by in the distance on 1-44. “That new road is a whole lot safer,” she said quietly. “It was bound to come.”

She wished us good luck and she and her daughter walked around to the back of the empty, windowless Ozark Courts. The restaurant in back had been converted into a very nice house, but from the front it was impossible to tell anyone lived there.

Central Missouri was Jesse James country. Competing signs wanted us to visit one of several true James Gang hideouts in the nearby river caves. By mid-afternoon the heat in Missouri was astounding and the idea of hiding in a cave began to have a lot of appeal. We didn’t know at the time, but we were seeing the first weeks of one of the hottest, driest summers ever in the Southwest; a livestock killer. We stopped at the Windmill Restaurant near Stanton, a restaurant which really has a huge windmill (motor-driven, in an odd twist of technology) and drank a few gallons of iced tea in the cool darkness of the place. When we left the heat and sunlight hit us like a pail of white steam.

Wine country signs for the Rosati Winery began to appear along the highway, so we stopped in the little town of St. James to buy some wine in celebration of our anniversary. A sporting goods store advertised “Minnows, Worms, Packaged Goods.” Not being all that fond of bait, we settled on Packaged Goods and bought a bottle of Rosati Concord.

In western Missouri old 66 had some trouble deciding which side of the Interstate it wanted, so we had to do some switching at overpasses and exits. Much of the road is still used as a sort of frontage road, or an alternative to local farmers who don’t want to bother with the limited access of 1-44, and the pavement is in good shape. The old concrete slabs have been paved over with a smooth salmon-colored tarmac of some kind. The road was unpatrolled, but we slowed down a few times when we found ourselves under scrutiny by state troopers on the nearby Interstate. The rest of the time it was an exhilarating high speed roller coaster through the hills.

The Suzuki was hard to hold at low speeds. It cruised so smoothly and effortlessly at 90 mph and above that other speeds felt willfully slow. At around 75 mph the air behind the Silhouette fairing became almost still. We could hold high speeds without fluttering to death and a pleasant sense of tranquility, almost a speed euphoria, set in. Above 80 we'd draw ourselves into a silent shell in all that motion, the engine and wind noise seeping past our ear plugs with the sound of a bullet whine. High speed has a serenity of its own, a relaxed flow not found at lower velocities. And when the radar detector went off, as it did approaching one small town, it was like having a phonograph needle suddenly skate across the grooves of your favorite record. The spell was broken. You slow down to 55 and it feels like covered wagon speed; you are sure you could hop off the bike and run along side picking flowers. Climbing back to 90, you are always amazed at the shortness of distance between two towns. You get into high gear and suddenly you are downshifting again. Barb and I talked about it at lunch; the smooth abandoned highway was turning us into speed junkies.

By nightfall we were headed into Joplin, Missouri, and 10 mi. from town we passed a small badge-shaped sign that said 66 West. It was the first written admission on the entire trip that there was indeed a highway by that name. In every other town and intersection it was either nameless or stuck with some dull municipal title like Frontage Road or Business 55. Somehow it was unfair to pin those unimaginative new names on the old road. A sense of tradition would have left it Route 66, just as Kennedy Airport should have remained Idlewild (Lord, what a beautiful word that was to have erased from our maps). But here, on the edge of Joplin, was a sign that > said 66 West. We got off to take a picture.

To travelers the town was not Joplin, Missouri, but Joplin Next Five Exits, and no one strayed very far from the exits.i4

We’d planned to celebrate our anniversary in Joplin by staying at a nice old downtown hotel, going out for dinner and maybe a movie later, and opening our bottle of Rosati Concord. On entering town our hopes faded. We could find no movie theater anywhere near the center of town and the only downtown hotel looked like it had been closed since the Korean War. There were no people on the street and very little traffic. The only activity we found was a revivalist tent meeting in a windswept field at the edge of town. It was another city where the open-all-nightlife had been drawn away to the junctions of highway and interstate. To travelers the town was not Joplin, Missouri, but Joplin Next Five Exits, and no one strayed very far from the exits.

We gave up the search and headed out of town to the Interstate, where we found a motel and a nearby restaurant staffed by some high school girls who seemed to be getting the most out of their grape gum. We had a dinner of enchiladas out of a can sprinkled with a kind of cheese product. The enchiladas were cold, but were served with hot lettuce; proof that lettuce heats faster in a microwave oven.

The number of people in the restaurant business who can’t cook to save their lives is staggering. If they were plumbers our houses would all be flooded. If they worked for the government things would be just as they are now.

Back at the motel we celebrated our anniversary with the Rosati Concord from our tankbag. It was good; mellow without being too sweet, and had a nice full flavor of red grape. A little island of quality that almost made up for the lack of movie, grand hotel and good dinner.

West of Joplin 66 is a real highway with traffic and road signs. It enters Oklahoma past a sign that reads “Entering Indian Country.” Where 66 and the Interstate cross you are offered a choice: “Will Rogers Turnpike. Toll Ahead”, or “Free Road, 66 West.” We figured Will Rogers himself probably would have chosen the Free Road, so we took that. Oklahoma is the Sooner State, named after those enterprising types who jumped the gun in the land rush, and we passed Sooner Cafes, Sooner Hotels, Sooner Used Cars and Sooner Bars and Grills in the dozens of small towns along the highway. The land flattened out a bit and new state technical college in one town advertised, among its other accreditations, a New Storm Cellar. The western sky was full of high cirrus clouds and we passed through a landscape of small slag mountains from zinc mines. Another road sign read “Buffalo Ranch Ahead. Live Buffalo.” That last apparently to discourage traveling flies.

True 66 continued all the way through Tulsa and Oklahoma City, 1-44 taking most of the traffic load so 66 could carry the local traffic. Oklahoma City, true to song, looked oh so pretty but was very hot at noon.

We were both sleepy by mid-afternoon and pulled into a coffee shop in a small town west of El Reno. There was no one on the street and the sidewalk was raised high off main street, Dodge City style. A strong late afternoon wind was blowing and a faded Greyhound sign creaked in the wind above an abandoned waiting room. As we took off our helmets a late Forties DeSoto pulled up and a woman and little girl, both in cotton print dresses, got out of the car. The wind swirled up a cloud of dust in their faces and the little girl covered her nose and mouth with a white handkerchief and they went into the coffee shop. A chill passed over me. I hadn’t imagined a scene like this since the last Woody Guthrie album I listened to. This was dry country and it was suffering through an unusually dry and hot summer. I had a feeling the dust bowl and the Great Depression might be over, but the weather here wasn’t so sure. The wind in Oklahoma certainly did come sweeping off the plain.

We stopped for the night in Shamrock, Texas, “The Most Irish City in America,” and checked into the Shamrock Inn and then rode into town, which actually had a working movie theater. “Foxes” was playing. A man and wife and their little boy climbed out of a pickup and bought tickets just ahead of us. The man collected his ticket and said, “I shore do hope your air conditioner’s workin’, or else we’ve just wasted five bucks.” The girl in the booth smiled. “It shore is,” she said, “and the movie’s just fixin' to start.”

The street was dead when we went into the movie, but we came out to find a virtual parade of pickup trucks going nowhere, cowboys and their dates honking at one another. The main street bars were busy and Waylon Jennings’ heavy thumping base runs could be heard from the sidewalks. We had a beer in a friendly, crowded bar, then went back to the motel for a late dinner. At midnight the air was still wiltingly hot. On the wall of our room was a shamrock-studded Irish blessing which began “May the road rise to meet you . . .” As a motorcyclist I wasn’t so sure 1 liked that image. But it ended with a promise of wind at our backs.

When you travel 66 you have different feelings about the changing landscape. In the Midwest your thoughts and observations are largely botanical in nature, full of trees, valleys and rivers; in west Oklahoma and Texas the theme is agricultural, all cattle ranches and big farms; but in the Southwest, very near the border of New Mexico, the landforms become mystical. The flattopped buttes and the layered, painted sandstone, the purple tinge of distant ranges and the clean dryness of the place create a sense of peace and stillness that is more a state of mind than a geography. Georgia O’Keeffe had it in her desert paintings. You turn off the motorcycle and the loudest thing you can hear is your own breathing and heartbeat.

Where Route 66 is not the only highway across New Mexico it splits off from 1-40 and runs parallel to it in unused isolation. We stuck to the old highway, an endless succession of concrete slabs divided by tar seams. Broken up, they would make enough patios for all of Long Island or enough foundations for all the tract homes in suburban Los Angeles, or the parking lot for one really large K-Mart. We are a rich country, I thought, that can abandon 2000 mi. of pavement, our own Appian Way, buy an entire new right-of-way nearby and build another 2000 mi. of fourlane. A lot of measuring, grading and co 'testing of property rights must have gone into both roads (“Sorry folks, the new ro<. has to go right through the front porch of your homestead.”)

For the photographer of bygone Americana, old 66 offers a lot of opportunity in the Southwest. The road is littered with the bones of truckstops, cafes and motels left high and dry by 1-40; it is a virtual gallery of Art Deco signs and architecture and old American sedans left overturned in the dying cockroach position, usually riddled with bullet holes. We saw the remains of our first Burma Shave signs in New Mexico, everything weathered away but the word Shave on the last sign.

A brilliant red desert sunset had us about 30 mi. east of Gallup on 1-40. Barb nudged me and pointed to the railroad track which paralleled the highway about a quarter mile away. We were being passed by El Capitan, the flagship passenger train of the Santa Fe Line, a train I rode to California as a kid.

“How fast do you think it’s going?”

“About 80 or 85.”

“Let’s find out.”

I rolled on the throttle and pegged our 85 mph speedometer but the train contained to pull away. The tracks were straighter and flatter than our road. “We’re going to beat that thing to Gallup,” I shouted to Barb. “Hold on.” There are few opportunities in life, I reasoned, to race the El Capitan down Route 66 with a fast motorcycle into a blazing red desert sunset. At 6500 rpm, which computed to about 105 mph, we began to gain on the train.

We crested a rise in the road and suddenly noticed a mean looking guy in mirrored sunglasses surrounded by a police car. He was parked in the median strip. 1 jumped on the brakes hard, enough to leave permanent scars in all three brake rotors. The cop either didn't notice us or thought we always traveled down the road with smoke pouring off our front tire, front suspension bottomed, rear tire chattering, Barb climbing up my back and our facial features distorted from negative G-forces. He didn’t follow so we shrugged and rolled back up to speed. We beat the train into downtown Gallup by about 30 sec. after 30 mi. of unmerciful flogging of the Suzuki, which handled the job easily.

We found our grand hotel in Gallup. It was a place called El Rancho, a big old lodge on Gallup’s main street, full of dark timbers, balconies, log furniture and Indian rugs; a sprawling gracious place. The waitress at breakfast told us Hollywood movie crews used to stay there on location. They made They Passed This Way, Red Mountain, Ambush, and Billy the Kid just outside of town. Gregory Peck, Alan Ladd, Robert Taylor and many others had stayed there, and as a teenager she had waited on their tables.

We left Gallup in the morning, planning to push all the way to L.A. We wound through the beautiful Painted Desert on 1-40, old 66 nowhere in evidence and apparently buried beneath the new pavement. We stopped to gaze down into the famous Winslow meteor crater and enjoyed the signs on the way in: “Free Petrified Wood With Fill-Up. See Painted Village Indian Teepees. See the Live Buffalo. See Winslow Crater, Established 20,000 B.C. Prototype of Lunar and Martian Crater.” Established? Protoype? Oh well.

Leaving Winslow we saw a sign which read, “Red Man Tobacco. America’s Best Chew.” That’s quite a claim, I thought, and amused myself for the next 40 mi. trying to picture the entire staff of Consumer Reports and the Consumer Protection Agency turning green around the gills and retching for a solid week as they sampled every known brand of chew to determine if Red Man was really America’s Best. “Simpson, that’s my spitoon you’re using.” “Sorry, Miss Jones.” “Aaaaarrrrgghh . . .”

We climbed the mountains into Flagstaff, where we stopped for lunch. I ordered a milkshake and got one which contained no milk and hadn’t been shaken.

It was a plastic cup of whipped non-dairy product, and I felt ashamed for eating it instead of making a scene and berating the management. Barb and I vowed to visit a non-dairy at the first possible opportunity, to see where the cows were not kept and tour the missing barns and stanchions.

East of Kingman we hit the last really big chunk of Route 66, a loop which circles north of 1-40; 80 mi. of nearly empty highway that arced through the rugged desert country just south of the Grand Canyon. It passed through 10 small towns struggling to survive in the barren landscape, some doing better than others. There was no shortage of gas stations with plywood nailed over their windows.

We descended into the lower desert heat at Needles, which sounds hot, crossing the California border at Lake Havasu, as the dammed up remains of the Colorado River are known there. The higher mountain landscape gave way to Joshua trees, cacti and the occasional palm.

We crossed the California desert in heat that strained credibility. The air rushing past us was like something vented from a restaurant kitchen fan, the one over the oven and deep fryer. 1 wasn’t sure that an air-cooled engine would keep running when the air got hotter than peak combustion temperature, but the Suzuki seemed less bothered than we did. Darkness on the desert brought almost no relief. At 1 1:30 that night I almost crashed swerving to avoid a black pavement patch I mistook for an animal and decided Barstow' would be a good place to find a motel.

In the clear morning desert sunlight we came off the high desert at Cajon Pass and began our long descent into Los Angeles. The steep downhill highway was riddled> with cops, apparently looking for fast coasters wasting gas. The landscape suddenly began to look like the Los Angeles of legend; the Biblical trees, tall Lombardy poplars, eucalyptus, palm trees bent like sails in a breeze, vines and red flowers overgrowing the bridges, and that particular brand of L.A. sunlight that turns everything into a muted, sun-softened pastel tone; none of the stark, glaring sharpness and spininess of the desert. Irrigation works wonders, combined with sun.

Towns founded with great expectations and inherited by people who didn’t seem to care

Suddenly we were in San Bernardino, still on old 66. The remnants of a main route into a big city are still there, really old gas stations and motels, mixed with such valuable new services as poodle breeding, Tai Kwando instruction and billiard table refinishing. We rambled past the beautiful old Spanish buildings of Rancho Cucamonga, the oldest winery in California, and endless developments of encroaching earthtone housing developments. Stuck here and there in all the newness and commercial glitter were a few early Spanish-style homes and ranch houses, small remnants of taste and elegance looking as out of place on the highway as Catherine of Aragon at a Donut Hut.

Then through Claremont where huge eucalyptus trees line 66, past the Equestrian Estates of Glendora where highly paid executives can be cowboys evenings on their five-acre spreads, around the manicured Santa Anita race track, past Azusa City Hall, the Conrock gravel pits, the nice old homes of South Pasadena near the Huntington Library and into what Ross Macdonald called the sun-blinded streets of L.A. Sixty-Six got lost somewhere in those streets, so we took the San Diego Freeway south to the CW offices in Newport Beach and our nearby home. After 2500 mi. of heat and drought, it was cool by the coastline and an early afternoon fog was rolling in.

We parked the bike in the garage, unloaded the pack and tank bag and leaned them against the living room wall to be unpacked when we had more energy. We got the mail, mixed up a pitcher of Margueritas, and sat out on the back porch to relax.

When you’ve just finished a big trip it seems only right to have some conclusions.

I thought about the trip, looking back at it through that long, slightly hazy tunnel that surrounds a highway journey, especially a disjointed Lost Highway journey. After some rumination and half a pitcher of drinks I decided the trip had left me with two impressions.

First, as long as there are so many of us we are lucky to have four-lane highways.

It’s easy to romanticize over the old twolane, but today it would be like any other overcrowded highway, and the romance would soon cool. Those sections of 66 where the old two-lane was still the only highway were a dusty, hazardous alley full of truck blast, train crossings, potholes, detours infested with orange flags and loose gravel, slow campers, trundling mobile homes and dangerous frustration. There was too much traffic for the old road. We had it best, being able to choose between the empty freedom of the abandoned highway or the smooth efficiency of the Interstate. People who didn’t like the old road didn’t have to use it, but at least it was there; or parts of it were there. As Chuck Berry said, “Anything you want we got it right here in the USA.”

Which led to another thought on the trip, and that was the tremendous variation in towns, restaurants, hotels and people along the highway. There were prosperous farm towns, pretty little places out of an Andy Hardy movie lot, with white picket fences, tidy main streets and bandstands in the town park. And then there were towns slightly gone to seed, where eroded expectations had allowed everything built in the last 20 years to be done the cheap, easy way; towns founded by pioneers with great expectations and inherited by people who didn’t seem to care. There were good restaurants, terrible restaurants, nice hotels, poor hotels, good coffee, bad coffee, real milk shakes made with ice cream in stainless steel containers, and plastic cups of whipped nondairy product.

The contrasts were most vivid at the end of a trip. If you got out of your house, out of your town, and traveled down the road you noticed the sharp changes in quality. When you were out traveling the good things raised your expectations a little, so when you got home you remembered them and wanted to concentrate some of the good ideas in the place you chose to settle down and live.

At the end of the trip I thought maybe that’s what Todd and Buzz were searching for. Why they left their homes and towns and traveled Route 66 in a Corvette, other than the sheer fun of traveling. Maybe they were just taking the long way home and bringing something back when they got there. They were finding out how a real milk shake should taste, so when they finally settled down they would never, ever accept a plastic cup full of semi-soft nondairy ice milk food product as a substitute, and if someone tried to give them one they’d have enough sense to raise a little hell. They knew that travel is a gift you bring home.