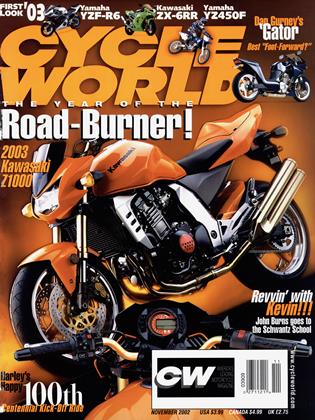

IN PRAISE OF THE ROAD -BURNER

Burly, baby, burly

DAVID EDWARDS

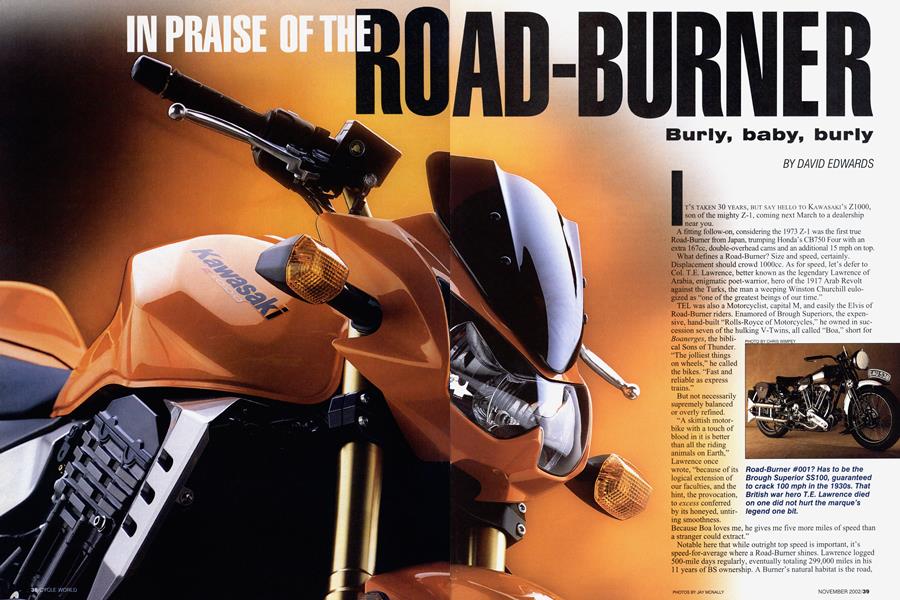

IT'S TAKEN 30 YEARS, BUT SAY HELLO TO KAWASAKI’S Z1000, son of the mighty Z-1, coming next March to a dealership near you.

A fitting follow-on, considering the 1973 Z-l was the first true Road-Burner from Japan, trumping Honda’s CB750 Four with an extra 167cc, double-overhead cams and an additional 15 mph on top.

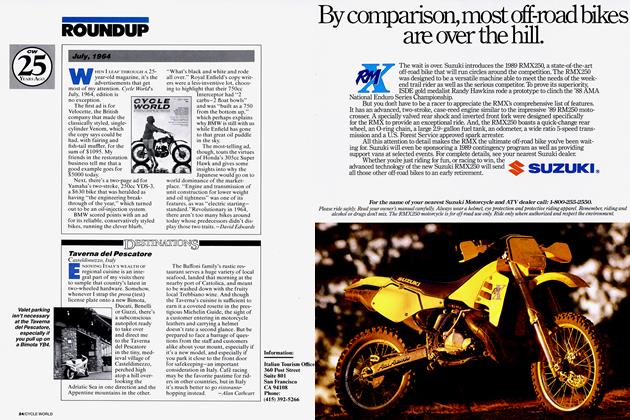

What defines a Road-Burner? Size and speed, certainly. Displacement should crowd lOOOcc. As for speed, let’s defer to Col. T.E. Lawrence, better known as the legendary Lawrence of Arabia, enigmatic poet-warrior, hero of the 1917 Arab Revolt against the Turks, the man a weeping Winston Churchill eulogized as “one of the greatest beings of our time.”

TEL was also a Motorcyclist, capital M, and easily the Elvis of Road-Burner riders. Enamored of Brough Superiors, the expensive, hand-built “Rolls-Royce of Motorcycles,” he owned in succession seven of the hulking V-Twins, all called “Boa,” short for Boanerges, the biblical Sons of Thunder.

“The jolliest things on wheels,” he called the bikes. “Fast and reliable as express trains.”

But not necessarily supremely balanced or overly refined.

“A skittish motorbike with a touch of blood in it is better than all the riding animals on Earth,”

Lawrence once wrote, “because of its logical extension of our faculties, and the hint, the provocation, to excess conferred by its honeyed, untiring smoothness.

Because Boa loves me, he gives me five more miles of speed than a stranger could extract.”

Notable here that while outright top speed is important, it’s speed-for-average where a Road-Burner shines. Lawrence logged 500-mile days regularly, eventually totaling 299,000 miles in his 11 years of BS ownership. A Burner’s natural habitat is the road, not the racetrack, or as the man himself put it, “So long as roads are tarred blue and straight.. .and empty and dry, so long am I rich.”

Today, repli-racers, marvelous pedigreed machines, have taken the performance high ground, but they are not RoadBurners. Track-day dandies, yes. Sunday-morning slingshots, yes. But too targeted, too hunkered down, too goddamned uncomfortable for real road use-at least for those of us no longer young and dumb, no longer limber of joint or washboard-tight of abs. There’s a reason Ducati’s new 999, successor to what many see as the sportbike of all sportbikes, has a lower saddle and higher handlebars.

Race-oriented sportbikes also have too much plastic, an evil required for all-out aerodynamics.

A Road-Burner’s powerplant should run uncloaked and on display, out there for all the world to see. Lawrence, who resigned his British Army commission in disgust of the post-WWI treatment of his Arab battlemates, only to later enlist in the RAF as a lowly aircraftsman, talked about the importance of engines.

“It is part of an airman’s profession to be ‘knowing’ with engines; a thoroughbred engine is our undying satisfaction. The camp wore the virtue of my Brough like a flower in its cap.”

TEL’s dashes across the Salisbury Plain, challenging blower Bentleys and low-flying Bristol biplanes to

contests of speed, came crashing to an end in 1935 when he pranged himself into a hedgerow and succumbed to head injuries six days later. Believe the official inquest and he died avoiding a wobbly boy bicyclist, or go with the conspiracists who insist the great man was offed by warmongers upon learning he had just agreed to talks with Adolf Hitler.

Whatever. It is T.E. Lawrence the rider, not the secret statesman, that we’re concerned with. One of us. The man who might as well have written the official Road-Burner’s handbook:

“Another bend and I have the honor of one of England’s straightest and fastest roads. The burble of my exhaust unwound like a long cord behind me. Soon my speed snapped it, and I heard only the cry of the wind...”

If we use Lawrence’s beloved SS100 as a blueprint, it’s clear that Kawasaki’s designers stayed pretty close to the script with the Z1000. Starting at the front, a fly screen to knock down the windblast and deflect at least a few suicidal bugs. A solo saddle, ’cause you can’t make any real time haulin’ your honey-though, if you insist, the Z’s rear cowl pops off to reveal a decent pillion pad. Road-Burners should celebrate their exhaust systems, not make do with the ubiquitous 4-into-l glorified coffee can or, worse, a style-less lump tucked away and hidden, a la Buell. Broughs had doublefishtails; the Z1000 has twin 2-into-l-into-2’s, very Italianesque, crafted from stainless-steel then heat-treated to tum a warm, straw-colored hue. Statement made. The Colonel might not care for the Z-bike’s dazzling orange livery-then again, he did specify nickel-plated gas tanks for Boa. The Kawasaki can also be had in black (with a red seat to match the engine’s inset plastic case sliders).

While the Z1000 is new-for-’03, many of its parts are familiar, borrowed as they are from various ZX-9R models. Upside-down fork and excellent four-piston Tokico front brakes are from the 2002 Niner. So, too, the tri-spoke wheels, the rear carrying 190-series rubber. Rear damper is another ’02 part. Swingarm is from the 2000-01 model, without the extra bracing of the latter bikes.

Unlike the ZX-9’s alloy piece, the 1000’s main frame is tube-steel, a cost consideration-product planners say the new bike will retail somewhere above the ZRX 1200’s $7900, but below $9K.

The frame’s rear “spar” is a sheetmetal ruse, though it does a nice job of stylistically tying into the radiator shroud. Sorry, home mechanics, there is no centerstand.

If the engine looks a little different from the ZX-9’s, it is, at least up top. For packaging reasons, the sportbike’s downdraft carbs had to go, replaced by fuel-injection throttle bodies located conventionally behind the cylinders. But what the intake tract taketh way, the boring bar may giveth back. Bigger pistons give the Z a displacement bump to 953cc. Horsepower will probably still be down compared to the 9R’s 130 bhp, but the new bike should be healthy nonetheless. A good guess would be 115-120 horsepower at the rear wheel. Plenty.

While they were recasting the block and head, Kawasaki’s engine team added ridges and vestigial finning to the cylinders, functionally worthless but aesthetically pleasing.

The latter describes the rest of the bike. Muscular and multi-faceted, the Z1000 commands attention, easily the most interesting design to spring from the House of Kawasaki in years. The style squad has obviously kept track of the British streetfighter scene and French tuner specials. This is what you get when you turn young, talented designers loose and let them design, not just reinterpret 1940s Indian Chiefs (Drifter), 1950s Harley Duo-Glides (Vulcan), 1960s Triumph Bonnevilles (W650) or your own 1980s AMA Superbikes (ZRX1200). Even better news, we hear there’s more where the Z1000 came from.

“They’re goin’ crazy over there,” said a jazzed U.S. Kawasaki higher-up just back from Japan. “I don’t know what they’re putting in their water.”

Whatever it is, may we suggest double-rations all ’round?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Other Side of Speed

November 2002 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsA Morning In Italy

November 2002 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCLiving In Harmony

November 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

November 2002 -

Roundup

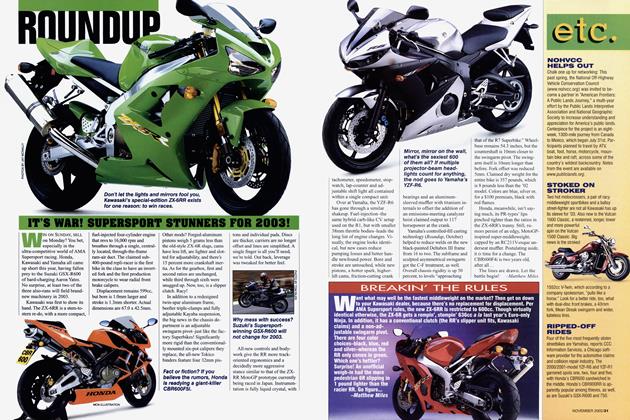

RoundupIt's War! Supersport Stunners For 2003!

November 2002 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupBreakin' the Rules

November 2002 By Matthew Miles