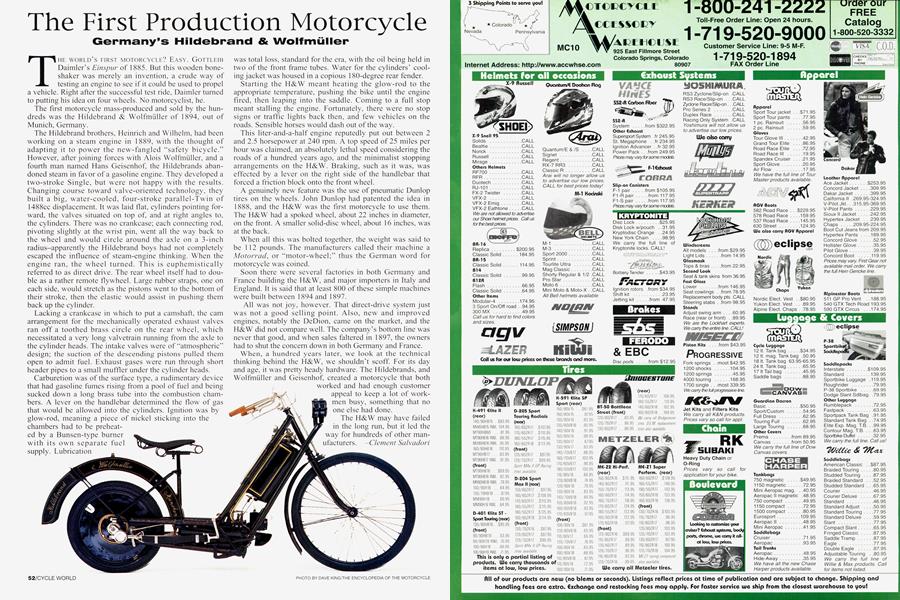

The First Production Motorcycle

Germany's Hildebrand & Wolfmüller

THE WORLD'S FIRST MOTORCYCLE? EASY. GOTTLEIB Daimler's Einspur of 1885. But this wooden boneshaker was merely an invention, a crude way of testing an engine to see if it could be used to propel a vehicle. Right after the successful test ride, Daimler turned to putting his idea on four wheels. No motorcyclist, he.

The first motorcycle mass-produced and sold by the hundreds was the Hildebrand & Wolfmüller of 1894, out of Munich, Germany.

The Hildebrand brothers, Heinrich and Wilhelm, had been working on a steam engine in 1889, with the thought of adapting it to power the new-fangled “safety bicycle.” However, after joining forces with Alois Wolfmüller, and a fourth man named Hans Geisenhof, the Hildebrands abandoned steam in favor of a gasoline engine. They developed a two-stroke Single, but were not happy with the results. Changing course toward valve-oriented technology, they built a big, water-cooled, four-stroke parallel-Twin of 1488cc displacement. It was laid flat, cylinders pointing forward, the valves situated on top of, and at right angles to, the cylinders. There was no crankcase; each connecting rod, pivoting slightly at the wrist pin, went all the way back to the wheel and would circle around the axle on a 3-inch radius-apparently the Hildebrand boys had not completely escaped the influence of steam-engine thinking. When the engine ran, the wheel turned. This is euphemistically referred to as direct drive. The rear wheel itself had to double as a rather remote flywheel. Large rubber straps, one on each side, would stretch as the pistons went to the bottom of their stroke, then the elastic would assist in pushing them back up the cylinder.

Lacking a crankcase in which to put a camshaft, the cam arrangement for the mechanically operated exhaust valves ran off a toothed brass circle on the rear wheel, which necessitated a very long valvetrain running from the axle to the cylinder heads. The intake valves were of “atmospheric” design; the suction of the descending pistons pulled them open to admit fuel. Exhaust gases were run through short header pipes to a small muffler under the cylinder heads.

Carburetion was of the surface type, a rudimentary device that had gasoline fumes rising from a pool of fuel and being sucked down a long brass tube into the combustion chambers. A lever on the handlebar determined the flow of gas that would be allowed into the cylinders. Ignition was by glow-rod, meaning a piece of nickel sticking into the chambers had to be preheated by a Bunsen-type burner with its own separate fuel supply. Lubrication

was total loss, standard for the era, with the oil being held in two of the front frame tubes. Water for the cylinders’ cooling jacket was housed in a copious 180-degree rear fender.

Starting the H&W meant heating the glow-rod to the appropriate temperature, pushing the bike until the engine fired, then leaping into the saddle. Coming to a full stop meant stalling the engine. Lortunately, there were no stop signs or traffic lights back then, and few vehicles on the roads. Sensible horses would dash out of the way.

This liter-and-a-half engine reputedly put out between 2 and 2.5 horsepower at 240 rpm. A top speed of 25 miles per hour was claimed, an absolutely lethal speed considering the roads of a hundred years ago, and the minimalist stopping arrangements on the H&W. Braking, such as it was, was effected by a lever on the right side of the handlebar that forced a friction block onto the front wheel.

A genuinely new feature was the use of pneumatic Dunlop tires on the wheels. John Dunlop had patented the idea in 1888, and the H&W was the first motorcycle to use them. The H&W had a spoked wheel, about 22 inches in diameter, on the front. A smaller solid-disc wheel, about 16 inches, was at the back.

When all this was bolted together, the weight was said to be 112 pounds. The manufacturers called their machine a Motorrad, or “motor-wheel;” thus the German word for motorcycle was coined.

Soon there were several factories in both Germany and Lrance building the H&W, and major importers in Italy and England. It is said that at least 800 of these simple machines were built between 1894 and 1897.

All was not joy, however. That direct-drive system just was not a good selling point. Also, new and improved engines, notably the DeDion, came on the market, and the H&W did not compare well. The company’s bottom line was never that good, and when sales faltered in 1897, the owners had to shut the concern down in both Germany and Lrance.

When, a hundred years later, we look at the technical thinking behind the H&W, we shouldn’t scoff. Lor its day and age, it was pretty heady hardware. The Hildebrands, and Wolfmüller and Geisenhof, created a motorcycle that both

worked and had enough customer appeal to keep a lot of workmen busy, something that no one else had done.

The H&W may have failed in the long run, but it led the way for hundreds of other manufacturers. —Clement Salvadori

View Full Issue

View Full Issue