Birth of the GT

The modern sporting V-Twin owes its existence to one Italian company saving itself from oblivion 30 years ago

MARK HOYER

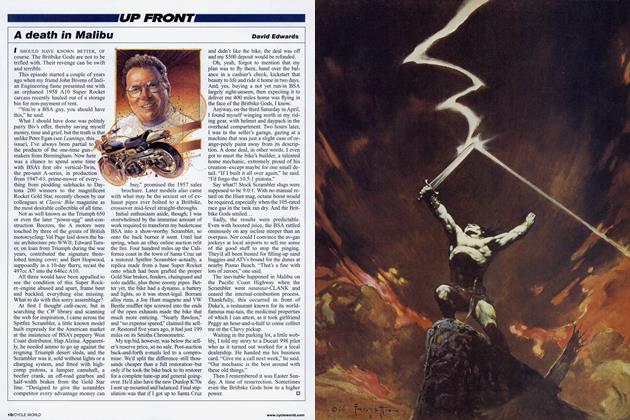

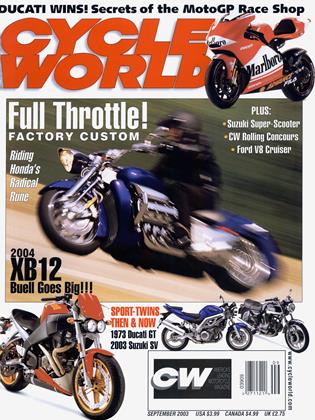

IT WAS LIKE ELECTRIC ARCS WERE FLASHING BETWEEN THE TWO BIKES, across the decades. It was as if this candy-blue Suzuki SV1000 was channeling the spirit of this superbly preserved Ducati 750 GT, the original modern V-Twin sportbike, which happened to be sitting next to it due to some weird confluence of events—like commuting. But there, right in front of us in the CW parking lot, was the evolution of the GT, the lineage of the 90-degree V-Twin sportbike, bookends on a class that was born in Italy in the early l970s as a builder of small, sporty Singles sought out of necessity to build itself a new image and big bikes for the burgeoning U.S. market that demanded them. There had been a few other 90-degree V-Twins before, but this was the seed that spawned what has become a rich and diverse two-cylinder universe populated by bikes with this peculiar layout. If you expand the list to include Twins that aren't at right angles, the range of sporting machines is wider still, from KTM's dirty Adventure to Aprilia's magic Mille.

So while this is certainly Ducati’s empire, the validity and durability of the form is demonstrated by the existence of bikes like the SV1000, which comes from a land half a world and three decades away, and is a maximally polished, wonderfully complete expression of the sport-Twin genre.

What is it about this kind of engine? There’s a certain balance, the sound, feel, power, character. Also, even if you can’t see “through” most modem V-Twins, there is a still-friendly airiness to the architecture, particularly to a 90degree Vee, that invites the eyes back to look again, tirelessly.

These are not things one says about an inline-Four, for example. You can marvel at the four-cylinder, be impressed with its peak power, note how compact it can be made and how easy it is to package in a motorcycle chassis with a short wheelbase, but in some ways it can be off-putting. Do you remember the television vacuum tube? There was something

visible about it, a part in your hand, manipulating electrons, glowing with life, soulfully accomplishing the same things as its more modem and compact counterparts, the transistor and microchip. It just did the business with more style, more grace, more of a human touch. It’s this tangibility of work, the way you can almost visualize and touch the combustion in a Twin, the “space” between percussive events, that seems to speak to us.

A Four is more mthless and remote-pleasing in its own way, to be sure-but it’s like looking at modem art versus one of the Old Masters, equally beautiful, but somehow less inviting, colder.

The invitation here, of course, is to ride. Back-to-back spins on bikes separated by 30 years demonstrates one thing for sure: Progress really is progress! But even though the Ducati is hindered by its age, the core experience remains magically satisfying.

Warm, late afternoon sun was shining on the mountainside as long shadows made their way across some of the smoothest, emptiest winding roads in California. The even beat of the old 750 barking from the chrome Conti megaphones is a delicious soundtrack as I swing through the bends. BRRAAaaaaaaaap! What the...? It’s Canet on the SV, sliding past. I know I can catch him, but I don’t want to grind the footpegs off of this lovely old Duck. Did I mention it belongs to my boss?

No, you don’t bin the Chiefs beautiful, lowmileage 1973 Ducati, even in the name of honor. Besides, maybe I couldn’t catch Canet. Not because he’s got riding talent or anything like that. It’s because his SV1000 has fuelinjection, 250cc more displacement, and more than double the horsepower...

I’m not sure he was having any more fun than I was, however. The Ducati in its time was a revelation: powerful, smooth, reasonably light, with good suspension and brakes. Compared to a Norton of the day, it was easier to start, better handling and virtually vibration free, without any of the rubberengine-mount Isolastic nonsense necessary to quell the spirited shake inherent to a 360degree parallel-Twin. And even though a V-Twin was a strange thing indeed for a sportbike back then-as the esteemed Mr. Schilling points out in his accompanying story, “Queer Duck”-there was something glorious about this strange combination of Italian bike parts.

It still is a glorious revelation. Even with

just 38 horsepower on tap, ancient tires and a pair of Amal carbs, the GT’s power delivery feels ample and immediate, cornering easy and secure. It’s a surprisingly light-steering bike, despite its old-style geometry and long wheelbase of some 60 inches. But more than anything else, the most marvelous thing is that the suspension actually works. It is supple, controlled (for its age) and doesn’t get upset even if you push things a little in the vain pursuit of a fast guy on a new bike. The combination of ride and handling is much better than either my old ’74 Norton 850 Commando or ’76 Laverda 3C Jota lookalike. It’s easy to see why this Ducati made such an impression in the 1970s.

It was just such an impression that saved Ducati from the destruction that befell so many other Old World bike makers, and after three decades has spawned a whole class of imitators.

Which is the sincerest form of flattery. The beauty of the Suzuki SV1000 is that it does so much with this engine layout for so little money. For $8000, you get a bike you could have taken to the Imola 200 back in 1972, and righteously spanked Paul Smart and his 750SS. Sure, time travel isn’t fair, but neither is racing. Kevin Cameron tells a story of standing next to Smart in the pits at Imola, the old Ducati revealing one of the unfair advantages of its engine layout. “Smart, accustomed to racing British parallel-Twins whose peak rpm is limited by engine vibration, said, ‘They’re telling me this Ducati can go to 9750 rpm. That doesn’t seem right. They’re telling me if I have to, I can go to 11,000.’ A British Twin at the time could have turned perhaps

6700 rpm before it shook itself to death.” Crazy stuff, eh? Smart won the race, no word on whether he needed the extra revs. This’SV, meanwhile, could run at the old Ducati racer’s redline for the next year, without likely ill effect.

Yes, times have changed. Take the sheer computing power of the SVIOOO’s engine-control unit. The old Ducati’s “electronic” ignition was crafted back when Bill

Gates was just learning he was going to have to become a billionaire to stop the ass-kickings in junior high and beyond. The SV’s software, unlike Windows (Bill’s revenge!), never freezes up. In fact, the SV just...runs. Choke is automatic, idle-speed setting automatic. Engage the starter, and the bike just starts. Cold, the idle rises to about 2000 rpm, then quickly dials itself back to the standard 1300 or so. And that’s it. There’s no spitting back or funny business, just as much smooth, predictable power as you ask. The Ducati, meanwhile, has two Amal Concentric carbs, which you have to “tickle” to get things started-mildly pleasurable if only because it’s vaguely reminiscent of one or two romantic interludes of my past. The remarkable thing about this old Italian bike is the ease with which you set it running. Tickle one carb or two-your choice-turn on the key and simply step on-don’t kick-the kickstarter. It often lights before

starter. It often lights before you’re even through to the bottom of the stroke. Try that on your Commando! The boss even claims his GT has started when he was just kicking it through to find top dead center.

Back on the mountain roads, with the occasional ride up past 6000-foot elevation, and the magic of the SV’s fuelcomputing brainpower reveals itself. It still runs with perfect cleanness, responding to Canet’s camera-prompted wheeliefest in a predictable, won’t-spit-you-off kind of way. The poor Ducati got tragically rich in the thin air, yet another reason I had to let Don get away after he passed me. The twin Brembo discs on the Ducati (a single was standard at the time) are pretty nice brakes for the era, although they did get a little toasty during repeated hard stops. Shhhh, don’t tell David!

The SV1000 borrows its brakes from the GSX-R750. As you might expect, these four-pot Tokico calipers and 300mm discs get the job done on this 446-pound naked bike. Chassis geometry sports what has become almost modem classic numbers-24.5 degrees of rake and 3.9 inches of trail. Combine this with the 180mm wide rear tire (down 10mm from the old TL), fully adjustable suspension front and rear, and you get yourself one nicely turning modem motorcycle, a much friendlier piece than the TL1000S ever was.

The SV simply invites riding. The easy-turning, stable chassis, the ample, broad power, always available no matter the revs, makes this one of the most pleasant bikes to ride of the current era. The 90-degree V-Twin’s perfect primary balance means the engine has no unpleasant vibes, just the primal thump of big, 98mm pistons working in 66mm strokes.

Compared to the TL-S engine upon which this SV mill is based, many of the internal parts are lighter, valves are smaller and the intake system is altered. Big of 52mm throttle bodies on the Mikuni dual-butterfly fuel-injection system work with the changes to make this one snappy powerplant. It zings right up to the 11,000-rpm redline, with peak power of 103 horses coming about 2K before. Max torque approaches a wheelie-friendly 70 foot-pounds at 7200 rpm. We’re betting the new Ducati Monster S4R doesn’t have numbers much better than this, and it will cost $5500 more.

As much fun as riding the peak-power wave is, the refinement of this Japanese Twin makes it quite the fine travelling companion, too. Loaded with a tankbag and full fuel, the 4.5 gallons of gas the SV holds will carry you 180 miles in naked-bike comfort. It’s a real pity that this unfaired SV wasn’t available for our naked-bike shootout (“Modem Immaturity,” CW, June), because it would definitely have been in the running. The S-model we did include is a pretty great ride, but its sportbike-like clip-on riding position hurt it among all those tubular handlebars and the playful attitude they impart.

I guess we all owe it to the Italians for essentially inventing this class of motorcycle. Bom in Bologna, perfected in Hamamatsu, the GT lives. U

View Full Issue

View Full Issue