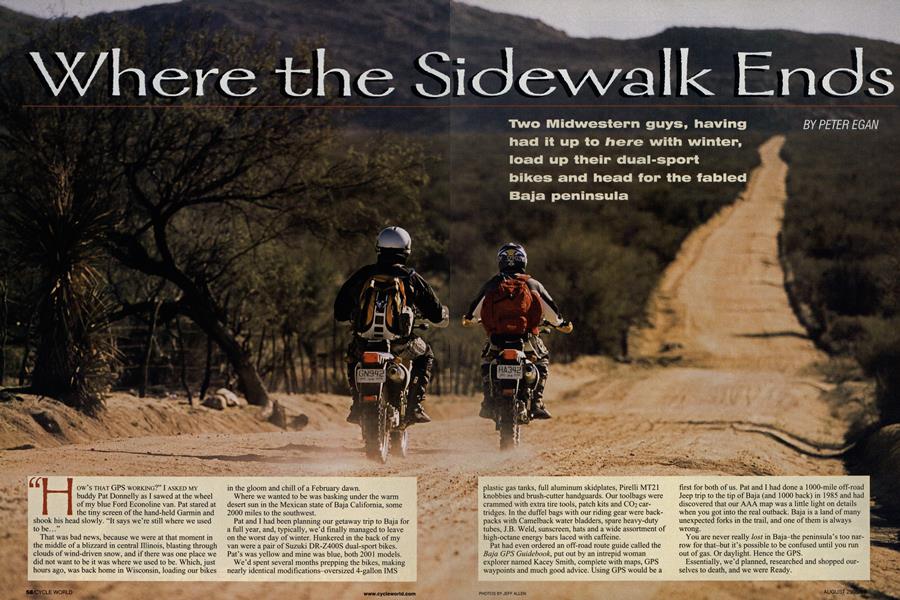

Where the Sidewalk Ends

HOW'S THAT GPS woRluNo?" I ASKED MY buddy Pat Donnelly as I sawed at the wheel of my blue Ford Econoline van. Pat stared at the tiny screen of the hand-held Garmin and shook his head slowly. “It says we’re still where we used to be...”

That was bad news, because we were at that moment in the middle of a blizzard in central Illinois, blasting through clouds of wind-driven snow, and if there was one place we did not want to be it was where we used to be. Which, just hours ago, was back home in Wisconsin, loading our bikes

in the gloom and chill of a February dawn.

Where we wanted to be was basking under the warm desert sun in the Mexican state of Baja California, some 2000 miles to the southwest.

Pat and I had been planning our getaway trip to Baja for a full year, and, typically, we’d finally managed to leave on the worst day of winter. Hunkered in the back of my van were a pair of Suzuki DR-Z400S dual-sport bikes. Pat’s was yellow and mine was blue, both 2001 models.

We’d spent several months prepping the bikes, making nearly identical modifications-oversized 4-gallon IMS plastic gas tanks, full aluminum skidplates, Pirelli MT21 knobbies and brush-cutter handguards. Our toolbags were crammed with extra tire tools, patch kits and CO2 cartridges. In the duffel bags with our riding gear were backpacks with Camelback water bladders, spare heavy-duty tubes, J.B. Weld, sunscreen, hats and a wide assortment of high-octane energy bars laced with caffeine.

Two Midwestern guys, having had it up to here with winter, load up their dual-sport bikes and head for the fabled Baja peninsula

PETER EGAN

Pat had even ordered an off-road route guide called the Baja GPS Guidebook, put out by an intrepid woman explorer named Kacey Smith, complete with maps, GPS waypoints and much good advice. Using GPS would be a first for both of us. Pat and I had done a 1000-mile off-road Jeep trip to the tip of Baja (and 1000 back) in 1985 and had discovered that our AAA map was a little light on details when you got into the real outback. Baja is a land of many unexpected forks in the trail, and one of them is always wrong.

You are never really lost in Baja-the peninsula’s too narrow for that-but it’s possible to be confused until you run out of gas. Or daylight. Hence the GPS.

Essentially, we’d planned, researched and shopped ourselves to death, and we were Ready. The plan was to drive the van into Baja and leave it at a couple of strategically located motels while we did two-day loops to distant overnight lodgings in the mountains. That way the van could serve as Mother Ship, a place to store extra tools, water, oil, dirty socks, etc. while we traveled with relatively light backpacks.

Three days after leaving home, we crossed into California at Yuma, stopped at a Shell station in Jacumba to fill up all tanks and buy Mexican insurance for the van and bikes. You must have Mexican insurance in Baja, by law, and it costs about $6 a day, per vehicle, for liability insurance only, more if you want theft

protection. We opted for the whole pack-

age, which cost $234, van and bikes, for seven days.

Taking scenic Highway 94 down to the border crossing at Tecate, we changed our money (about 10 pesos to the dollar) and bought tourist cards for $18 each (good for 6 months). Tecate is my favorite border crossing because it’s a small town with light traffic and almost no waiting.

Tijuana, on the other hand, can be a nightmare, and Mexicali is not much better.

Late in the afternoon, we drove east 30 miles to El Hongo, then took a washboard dirt road south about 20 miles to a resort motel called Hacienda Santa Veronica.

Washboard roads, incidentally, are a specialty of Baja. They have a Dept, of Washboard Research with a full staff of civil engineers who have figured out exactly how far apart the ridges have to be to shake every nut and bolt loose on your vehicle. Driving my van down to Santa Veronica was like piloting an air chisel.

The DWR is always in competition with the Office of Pothole Development, a friendly rivalry not unlike that between our own FBI and CIA. The dirt roads in Baja would be tragic if they weren’t so funny. You see middleaged couples hammering along in their dented Omnis and Fiestas with their hats jittering on their heads and wonder if they ever ask why their roads are so bad. It’s all a matter of low population and tax revenue, of course. Baja is a big place with few people and long distances, which is why we go there. If the roads were better, we’d stay home.

Hacienda Santa Veronica had a cold, empty feel when we got there. It was the hired help’s day off, and there were no other guests, as an off-road tour group was not slated to arrive until the next day. Nevertheless, a woman named Lourdes cheerfully opened the bar and restaurant, made a warm fire in the fireplace, whipped up some margaritas and cooked (after making the sign of the cross) us a great machaca beef dinner with fresh tortillas.

Pat and I unloaded the bikes, and in the morning headed out on a 150-mile ride to Laguna Hanson, a lake up in the mountains. It was all narrow dirt road of varying quality, with just enough sand, rocks, rain ruts and water crossings to keep our attention. This was Pat’s second dirt ride ever, and I hadn't been

off-road in Baja on a motorcycle

for 22 years, so we both needed a good break-in day of only moderate brutality.

We tried a stretch of single-track up a canyon, but heavy rains from the previous week had washed the trail into a jumble of boulders and tree roots, so we turned around and headed for the little village of Ojos Negros, where there was said to be gas.

We spotted a homemade cardboard Gasolina sign in the courtyard of a house and tractor-repair shop, but a woman came out and said they had no gas. She pointed at another

house diagonally across town and said they had gas. They didn’t, but pointed at another house. They didn’t either. Finally,

I saw a guy standing on his rooftop, waving his arms and pointing into his yard. Just like a neon sign for the Golden Nugget in Las Vegas, only live.

The man had a

drum of gasoline in the back of an old pickup, and he sucked on a hose and siphoned fuel into a plastic milk jug. Each of our bikes took one jug, at a cost of about $2.50 a gallon.

Fueled up, we made the last climb to Laguna Hanson, but it turned out to be a laguna seca-a dry lake. Last time I was here, it was a sky-blue diamond in a setting of tall pines, but last year’s drought had left the basin dry. We headed back in late afternoon, with a chill in the air and the sun low, hustling to the lodge just before dark. The tour group had arrived, New Yorkers on ATVs, led by a German exmotocrosser from San Diego named Sven. Sven rode the only two-wheeler in the group, a Honda XR400, and kidded his clients that he was still too young to ride an ATV.

“Those DR-Zs are nice bikes,” Sven said, looking at our Suzukis, “but in Baja, in the middle of nowhere, I like aircooling. Less to go wrong. XRs are tough.”

I agreed with him, but had to admit I was addicted to my DR’s electric starting. We retired to the restaurant, had another great dinner and sat around the fireplace all evening comparing brands of tequila and telling incredible but partly true stories.

The next day, Pat and I loaded our bikes into the van, juddered back to the highway and headed east on Mex. 2, taking the four-lane toll road over the spectacular Rumerosa Grade, whose flanks are a graveyard of smashed and burned cars. Crosses and memorials to the dead line the road; it’s the Flanders Fields of highways.

Descending onto the coastal plain, we motored into Mexicali.

Mexicali’s suburbs are a zone of bad construction, stray dogs, junked cars, Tecate Beer signs and blowing plastic bags, the air redolent with the aroma of sulfur and trash. But when you get to the center, it’s a bustling industrial town with a Wal-Mart and McDonald’s and lots of Americannamed factories, part of the NAFTA miracle that has cost us so many jobs in Wisconsin.

We turned down Mex. 5 toward San Felipe and just south of Mexicali motored through a vast city dump in the desert flats-buming tires, trash half-buried.

For miles and miles there are old tires everywhere, far as the eye can see, like spilled

black Cheerios. Mexico’s border with the U.S. is

never a pretty place.

But it quickly gets better. As you head along the salt marshes of the Gulf of California, traffic tapers off and after about 100 miles you come into the little fishing and tourist town of San Felipe, which sits charmingly on a white sand bay. The place is full of mariscos (seafood) restaurants and bars, with lots of retired gringos living in cottages and motorhomes on the nearby beaches.

We checked into the Motel El Capitán, a clean, modem place with an enclosed courtyard to protect bikes and trucks from prying eyes. After unloading the bikes, we headed off for dinner on a warm, balmy evening with the surf lapping the beach and a breeze rustling the palm trees. 1 suddenly realized that for the first time in months I was fully relaxed and not hunching my neck down into my collar to keep warm.

“There is a vast distance, geographically and psychically,” I said to Pat, “between this place and, say, Springfield, Missouri, during a blizzard.”

“Almost another planet,” he said.

In front of the International Restaurant (which advertised Mexican food!), we met Jeff Allen, a Cycle World photographer who’d ridden down from the home office in Newport Beach to join our little expedition for a day of riding and shooting photos that would capture our almost indescribable riding skills against the mystical Baja landscape. Jeff is a superb dirt rider who could easily zip ahead of us on the trail, with plenty of time (hours) to set up his camera gear and catch us roosting down the dusty trail.

Jeff was also mounted on a DRZ400S, a brand-new testbike with the small stock 2.6-gallon tank, so he had a couple of plastic gas bottles bungeed to the sides of his seat. He’d made it all the way from the office in one day, riding on dirt roads over the mountains rather than cruising down on the paved highway. Yet he looked completely relaxed and rested. Pat and I were dumbfounded.

In the morning we gassed up, slung on our backpacks and headed off into the mountains on a two-day ioop that would take us to the legendary Mike's

Sky Ranch and back. We rode out of town past the city dump without taking advantage of the many opportunities for tire puncture on old nails, metal scraps, cans, barbed wire, etc., and soon found ourselves following Jeff through miles of deep sand whoops across the valley floor.

To a person of 55 from Wisconsin who has gained 12 pounds over the winter and has had no exercise except to walk the dogs on those rare days when it’s above zero, several miles of repetitious sand whoops are the equivalent of your first day in Basic Training-all push-ups and deep knee bends. But we did not melt down and eventually got into the rhythm of riding in the sand, which is simply a form of fatalism. You abandon yourself to the constant sensation of imminent crashing, sit back on the saddle loose as a goose and keep the power on.

Pat caught onto this very quickly, and was soon riding faster than I was. I have an Early Tankslapper Warning System (ETWS) embedded in my brain that, tragically, prevents me from really dialing it on in deep sand. It has its roots in a high-speed face-plant I managed in the Barstow-to-Vegas dual-purpose ride one year. Yes, in the sand I am damaged goods.

In mid-morning, the trail opened on to a huge dry lakebed called Laguna Diablo (si, the dreaded Lagoon of the Devil; many enter but few return) and we pegged the throttles wide-open. My bike would pull about 70 mph in fourth, but bog in fifth. Pat, with a

Yoshimura pipe, richer jetting and K&N filter, could go about 5 mph faster and use top gear. But my stocker started and idled better, by way of feeble compensation.

We stopped halfway across the lakebed at a cluster of rustic buildings where the inhabitant, a small Mexican man, sells cold drinks and snacks. He had a pot of something mysterious brewing on an oil-drum stove. His house had a slightly evil smell, and the garage was festooned with a couple of severed goat’s heads, hanging from strings and dangling in the wind. Something about the place reminded me of either the last half-hour of Apocalypse Now! or an old Rolling Stones album I have. Perhaps this man was, in fact, the Devil himself, and the pot contained genuine goatshead soup. Or perhaps he was just an avid Stones fan.

In any case, the Cokes were icecold, and we got to pet several yellow dogs as we shooed away the flies. Soon another tour group arrived, fathers and sons all on motorcycles, led by a guide named Bruce Sanderson, who was a fellow car and motorcycle roadracer when I lived in California in the early Eighties. Good to see him again.

Like Rick’s place in Casablanca, sooner or later everyone comes to Baja. Or at least all the usual suspects do.

After more sand trails, we hit a short stretch of paved road on Mex.

3, then turned off on a dirt road with

a sign for “Mike Sky Ranch.” It was a beautiful road in the late afternoon sun, gradually turning just hilly, rocky and

twisty enough to be fun as you approach Mike’s. We took a single-track detour for several miles through the puckerbushes, just to build character, and I went wide in a corner and neatly sheared off an ocotillo tree with the brush-cutter on my left handguard.

Handguards are good, I noted. I’d have smashed every finger in my left hand, and taken the clutch lever off.

We finally came over a rise and saw Mike’s, a lovely rancho/motcl built around a pool in the palm of a high mountain valley. When we got off the bikes, it was Miller Time in a big way. Actually, Pacifica Clara time. We were tired and blissfully happy to be there. As we sat by the pool with a beer, it felt like the Promised Land.

Mike’s was originally conceived as a fly-in trout-fishing resort, and there’s a small airstrip, now closed (supposedly at the suggestion of the DEA) on the nearby mountaintop. But it was off-roaders more than fishermen who converged, making the place a Baja institution. The bar is plastered with business cards and bumper stickers from every off-road race team, bike-maker, buggy-builder and dirt rider in the world, with several generations of Cycle World decals in the mix.

Mike Sr., who looked like Caesar Romero, died a few years back with his wife in a car accident, but his son, Mike Jr., has kept the spirit of the place, and fixed it up better than ever. The rooms are clean, and furnished in elegantly simple Spanish style.

We had the traditional Mike’s dinner of steaks cooked over a mesquite fire, then returned to the bar for a beer and to watch Baja 1000 videos on TV with a big crowd of other riders who’d shown up in small groups.

Among them was none other than Jerry Platt. Jerry is an old Baja hand and Cycle World contributor, with whom I first rode to Mike’s 23 years ago on our annual CW Baja Trek. Jerry ran the first Baja 1000 in 1967 on a magazine-sponsored Norton 750 PI 1 scrambler, and his old race partner Vem Hancock was also in the bar. Traveling with them were Vic Wilson, who won the first Baja 1000 outright in a Meyers Manx, and his wife Betty Jean, former wife of the late Joe Parkhurst and co-founder of this very magazine. Baja royalty. They had all arrived in buggies and trucks.

The old Rick’s place syndrome again. Bruce Sanderson was there, too. It felt like the bar at a class reunion.

The next morning, Jeff split for home, and Pat and I filled our Camelbacks and mounted up. Incidentally, I’d never used one of

these “hydration systems” with a hose

and mouthpiece before, and it made a huge difference in how much water I drank because I didn’t have to take my helmet and goggles off to get a drink each time. Pat and I had brought lots of bottled water along in the van, but I ended up filling my Camelback bladder with tap water at all our hotels, without problem. Water is supposed to be good everywhere in Baja.

In fact, the only time I ever got sick here was from eating unwashed salad greens in Ensenada in 1982, just before a ride to Mike’s. Nature called so often it sounded like an echo chamber.

Pat and I cruised back to San Felipe on many of the same trails, and a few new ones, had a shrimp taco dinner that night in a little outdoor seafront café, then braced ourselves for the Big Ride the next day.

Rising early (for us), we rode down the gulf coast about 100 miles on a mixture of increasingly neglected roads and dirt trails, refueled at Bahia San Luis Gonzaga, then turned southwest on single-track trails. Our plan was to climb over the mountain divide, hit the main highway and head back north to the village of Catavina that night. On this leg, we decided to challenge ourselves a bit and take a trail marked on our map as “difficult” over the mountains.

And it was.

Picture 15 miles of steep stairs made of loose rock and boulders in a V-shaped canyon.

Which is another way of saying we beat ourselves to death for about three hours climbing out. I crashed into the side of the canyon wall while trying to loft my front wheel over a boulder about the size of a prize-winning hog. The sudden stop split my plastic gas tank at the rear mount and smacked my ribs into the left grip (the bruise is still there, in festive shades of iodine and Vicks-bottle blue). Gas trickled down onto my swingarm like a bab-

bling brook, but at least I was left with half a tank after the fuel level sank below the split seam.

Pat crashed about three times and hit his chest on the bars, hard. I heard his engine stop once and went back to find him splayed on the rocks with his arms and legs out and his bike lying on its side. “I’m just resting,” he said.

We got out of the canyon in a series of 30-yard banzai attacks on the rocks, punctuated by five-minute rests in relatively flat areas. About an hour before dark, we finally crested the grade and found ourselves on beautiful high-desert trails, with a mist of rain moving in.

At an abandoned mine called _

“Mine Camp” (which I immediately dubbed Mein Kampf, after our struggle up the mountain), we took a wrong fork in the growing darkness, but Pat’s GPS unit came to the rescue, pointing us back to the camp and off on a different trail.

Without Kacey Smith’s GPS coordinates, ^-*

we’d probably still be out there, eating grubs and seeds, these pages would be tragically blank, and our wives would be out shopping with the insurance money.

We passed an amazing little Baja institution called “Coco’s Comer,” a rancho and snack stop festooned with aluminum cans hanging from all the fences, glittering in the wind. Coco himself came to the gate and advised us not to

press onward toward Catavina because a) it was about 50 miles away, b) it would be much colder on the Pacific side of the mountains and c) it was almost dark and about to rain. He advised us to ride back down to Gonzaga Bay, whence we had come, a mere 30 miles away on the graded dirt road.

But just as Hillary and Tensing did not turn back from Everest, Pat and I pressed on into the gloom. Mainly because we wanted to have a margarita and stay at the upscale (for Baja) Hotel La Pinta, which I remembered as the best and only lodging in Catavina. In fact, it was almost the only building, miles from anywhere, in a spectacular setting of cactus and boulder fields-one of the most beautiful spots in Baja.

We got there, damp, cold and exhausted about 8 p.m. and found the place was full, as two large tour groups of BMW streetbikes were staying there, having come down the smoothly paved Mex. 1, the cowards. I naturally hadn’t gotten reservations because I’d never seen the place full.

Pat and I were very sad. Speechless, in fact.

But the clerk told us in Spanish (which I both speak and listen to bro kenly) that there was, in fact, another little motel about 400 meters up the road called Cabanas Linda, so we went there and found a room. Cheap ($20 for a double), clean and simple-two beds, a chair and a sort of shower nozzle/pipe-in-the-wall that actually emitted steaming hot water.

There w~s no room heat, but the beds had lots of blankets, which is the normal Baja answer to the national if furnace shortage.

As I fell asleep that night, after popping a Vicodin for my injured ribs, I said, "This is the best motel I've ever known."

We had breakfast at La Pinta the next morning and I filled my leaking tank at the nearby Pemex station, reasoning that our J.B. Weld and duct tape probably wouldn't stick to the soft, greasy plastic. We then hot-footed it 160 miles back

over the mountains, taking the “easy” road this time, with my bike stinking of gas fumes. We refueled in Gonzaga Bay and stutter-bumped back up the coast to San Felipe.

Late in the afternoon, we finally got back to our trusty Hotel El Capitan, where the owner had kindly let us leave our van. My bike had just gone on Reserve.

We climbed off the bikes stiffly, took off our dusty goggles, looked at each other like a couple of weary raccoons and shook hands. End of the Baja ride. Still walking upright, more or less, bikes still working.

Over fish tacos and beers on the waterfront that evening, Pat and I agreed we’d been lucky not to get stranded the day before. At one point in the rocky canyon we were about 30 difficult miles in any direction from another human being, a telephone or even a standing wall. A broken wrist or a broken bike would have been a Very Bad Thing.

Most amazing, though, over all those hard miles, was the toughness of our Suzukis. Pat said, “I cannot believe the beating these bikes take without failing.”

Our skidplates helped, of course. Both of us smacked into boulders several times, hard enough to break the cases or clip off a waterpump housing. And my left radiator had been bent like a banana, but had fortunately not sprung a leak. Sven, with his preference for air-cooled bikes, probably had a point. Still, we both made it with no trouble other than a pair of lost chainguard bolts, which we replaced with nylon tie-wraps.

Beyond the bikes’ capacity to absorb punishment was their ability to soldier through so many types of terrain without stalling, overheating or being deflected from the trail. The DR-Z400S has an amazingly plush ride and seems to soak up shock loads from rocks and rain ruts, while maintaining its direction, in a way that at times seems to defy physics. It wants to go where you point it, and the engine is like a bulldog crossed with a greyhound; it just never quits grinding out forward motion at the bottom end, yet feels lively at the top.

We were both worried about having only batteries and starter buttons-no kickstarters-before we left for Baja, but the little red buttons never let us down. And there is something wonderful about restarting a bike on a steep hillside with the push of a button, rather than backing it down to a level spot. One of the unwritten laws of kickstarting a dirtbike is that you usually have to do it when you’re so tired you can’t.

Overall, I would have to say that the DR-Z is a great trailbike, and an easy

bike to handle for riders at our level. Or, apparently, at any level. Jeff liked his, and Of s dirt ace Jimmy Lewis owns one. In any case, my hat is off to the Suzuki engineers who cooked up this particular brew. Pat and I did 700 miles off-road in Baja, and our

bikes got us out of a lot of tight spots.

With our week of Mexican insurance about to run out, we loaded up the bikes in San Felipe and headed north. At a clogged border crossing in Mexicali, we encountered an American customs agent who was so rude I told Pat I thought he was just testing to see if we would fight back. “Maybe if you don’t flash a little anger, they know you’re hiding drugs.”

“No,” Pat said wearily, “he’s just an unhappy guy.’

While the agent carefully inspected the contents of our van, people were passing money and documents back and forth through the iron bars of the border fence, 50 feet away. No wonder the guy was unhappy; he’d been given a hopeless job.

Not a very pleasant welcome home, but maybe we’d just been spoiled by the quiet, dignified politeness of the people in Baja farther south, away from the border.

And the food. And the beer. And the weather, too.

We hit yet another blizzard at the Missouri border on our three-day drive home, and arrived at my house on an evening when it was 18 degrees.

It’s a long drive in your van from

Wisconsin to San Felipe and back-our round trip was 4600 miles-but worth it. I’d do it again, and probably will.

There’s no place like Baja. It’s a big, dry, mountainous land, a wilderness large enough to perpetually frustrate easy commerce and settlement. The peninsula itself is like one of the desert plants that grow there-durable, spiny and full of defensive thorns. You can admire it, but it’s not easy to handle. It’s a place that resists domestication and change. I first rode there 23 years ago, and it’s just as good now as it was then.

Bad roads, of course, deserve most of the credit for this ageless charm.

May they never improve.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

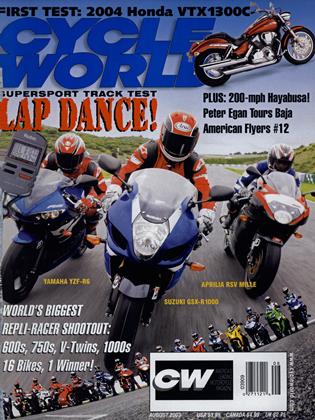

Up Front

Up FrontIssue No. 500

August 2003 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsRiding the Cheyenne Breaks

August 2003 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCPressing Matters

August 2003 By Kevin Cameron -

Department

DepartmentHotshots

August 2003 -

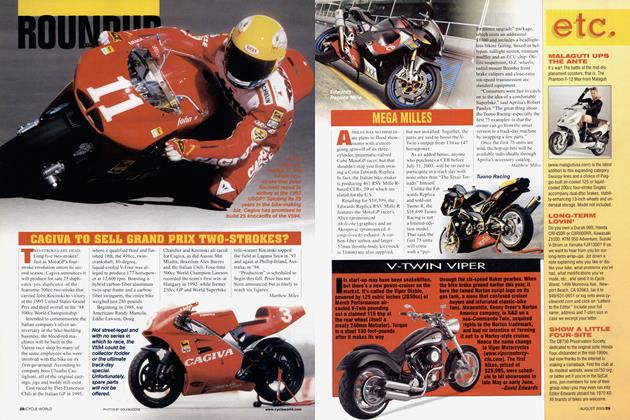

Roundup

RoundupCagiva To Sell Grand Prix Two-Strokes?

August 2003 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupMega Milles

August 2003