Dodging the dragon

TDC

Kevin Cameron

THE MORE RACES I ATTEND, THE MORE I realize that, in general, the safest rider on the pavement is the leader. When there is a crash, the top runner is seldom involved. Even when two or three closely matched riders battle for the lead, rarely do any of them fall.

This directly contradicts the ancient maxim, “Slow Down and Live,” so beloved by departments of public safety. The obvious converse, “Speed Up and Die,” suggests that the simple act of going fast brings deadly risk. Then why is so little of the crashing in races at the front? Riders with the skill, experience and equipment setup that allow them to lead races are usually persons of judgment and self-discipline, able accurately to estimate their margins of safety and to act rationally upon that knowledge. They know that the harder a rider pushes, the more frequent mistakes become, elevating the chance of falling.

Several times I have watched two riders race for the lead at Daytona, lap after lap, at very close quarters. There is no slipping and sliding, none of the histrionics we associate with pushing to the ragged edge of traction. Why not? Because both men in each case are determined to finish the race and take home maximum championship points. Both know the winner will be decided on the last lap. Therefore they cruise at high speed and low risk, sizing up each others’ styles, each man hoping to “rub off” the other in the passing of lapped riders. They stay out of reach of the rest of the pack by such fast cruising, but they are not racing. That comes at the end.

Very similar are Daytona Supersport races, with their tight lead groups of six to 10 600s that constantly shuffle the lead. Kurtis Roberts notes that there is no real racing until the last two laps. The rest-despite the hypertensive utterances of the race announcer-is just window dressing because no one can break the draft to pull away.

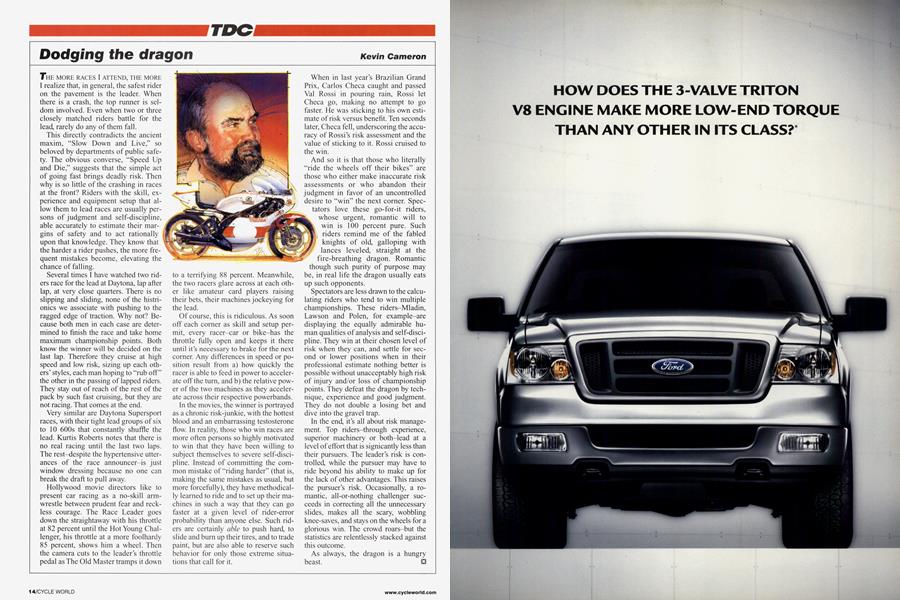

Hollywood movie directors like to present car racing as a no-skill armwrestle between prudent fear and reckless courage. The Race Leader goes down the straightaway with his throttle at 82 percent until the Hot Young Challenger, his throttle at a more foolhardy 85 percent, shows him a wheel. Then the camera cuts to the leader’s throttle pedal as The Old Master tramps it down

to a terrifying 88 percent. Meanwhile, the two racers glare across at each other like amateur card players raising their bets, their machines jockeying for the lead.

Of course, this is ridiculous. As soon off each corner as skill and setup permit, every racer-car or bike-has the throttle fully open and keeps it there until it’s necessary to brake for the next corner. Any differences in speed or position result from a) how quickly the racer is able to feed in power to accelerate off the turn, and b) the relative power of the two machines as they accelerate across their respective powerbands.

In the movies, the winner is portrayed as a chronic risk-junkie, with the hottest blood and an embarrassing testosterone flow. In reality, those who win races are more often persons so highly motivated to win that they have been willing to subject themselves to severe self-discipline. Instead of committing the common mistake of “riding harder” (that is, making the same mistakes as usual, but more forcefully), they have methodically learned to ride and to set up their machines in such a way that they can go faster at a given level of rider-error probability than anyone else. Such riders are certainly able to push hard, to slide and burn up their tires, and to trade paint, but are also able to reserve such behavior for only those extreme situations that call for it.

When in last year’s Brazilian Grand Prix, Carlos Checa caught and passed Val Rossi in pouring rain, Rossi let Checa go, making no attempt to go faster. He was sticking to his own estimate of risk versus benefit. Ten seconds later, Checa fell, underscoring the accuracy of Rossi’s risk assessment and the value of sticking to it. Rossi cruised to the win.

And so it is that those who literally “ride the wheels off their bikes” are those who either make inaccurate risk assessments or who abandon their judgment in favor of an uncontrolled desire to “win” the next corner. Spectators love these go-for-it riders, whose urgent, romantic will to win is 100 percent pure. Such riders remind me of the fabled knights of old, galloping with lances leveled, straight at the fire-breathing dragon. Romantic though such purity of purpose may be, in real life the dragon usually eats up such opponents.

Spectators are less drawn to the calculating riders who tend to win multiple championships. These riders-Mladin, Lawson and Polen, for example-are displaying the equally admirable human qualities of analysis and self-discipline. They win at their chosen level of risk when they can, and settle for second or lower positions when in their professional estimate nothing better is possible without unacceptably high risk of injury and/or loss of championship points. They defeat the dragon by technique, experience and good judgment. They do not double a losing bet and dive into the gravel trap.

In the end, it’s all about risk management. Top riders-through experience, superior machinery or both-lead at a level of effort that is signicantly less than their pursuers. The leader’s risk is controlled, while the pursuer may have to ride beyond his ability to make up for the lack of other advantages. This raises the pursuer’s risk. Occasionally, a romantic, all-or-nothing challenger succeeds in correcting all the unnecessary slides, makes all the scary, wobbling knee-saves, and stays on the wheels for a glorious win. The crowd roars-but the statistics are relentlessly stacked against this outcome.

As always, the dragon is a hungry beast. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue