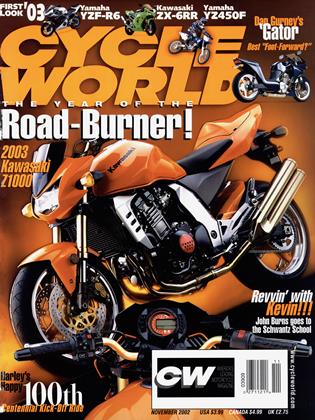

Gurney Alligator

When we say there’s nothing else like it, we mean it!

STEVE ANDERSON

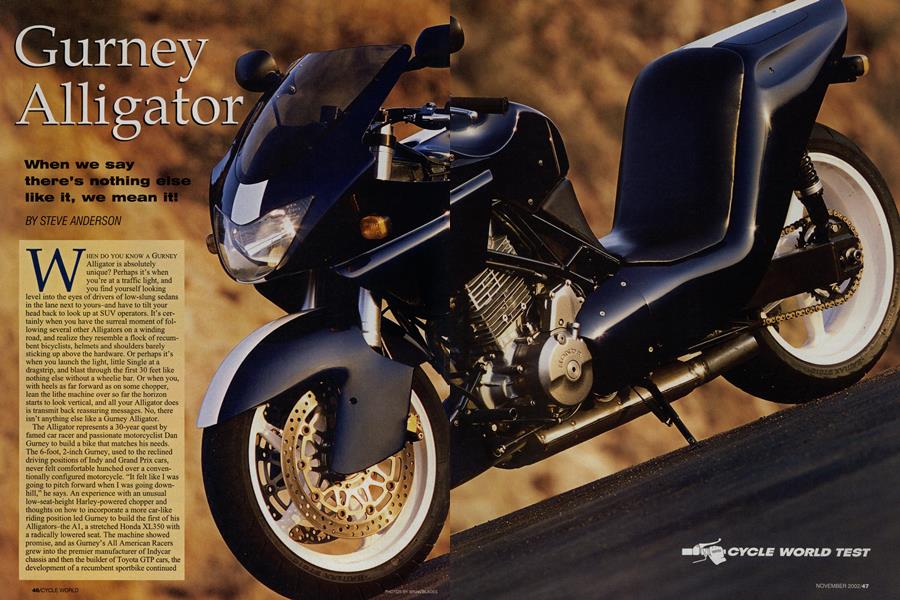

WHEN DO YOU KNOW A GURNEY Alligator is absolutely unique? Perhaps it’s when you’re at a traffic light, and you find yourself looking level into the eyes of drivers of low-slung sedans in the lane next to yours-and have to tilt your head back to look up at SUV operators. It’s certainly when you have the surreal moment of following several other Alligators on a winding road, and realize they resemble a flock of recumbent bicyclists, helmets and shoulders barely sticking up above the hardware. Or perhaps it’s when you launch the light, little Single at a dragstrip, and blast through the first 30 feet like nothing else without a wheelie bar. Or when you, with heels as far forward as on some chopper, lean the lithe machine over so far the horizon starts to look vertical, and all your Alligator does is transmit back reassuring messages. No, there isn’t anything else like a Gurney Alligator.

The Alligator represents a 30-year quest by famed car racer and passionate motorcyclist Dan Gurney to build a bike that matches his needs. The 6-foot, 2-inch Gurney, used to the reclined driving positions of Indy and Grand Prix cars, never felt comfortable hunched over a conventionally configured motorcycle. “It felt like I was going to pitch forward when I was going downhill,” he says. An experience with an unusual low-seat-height Harley-powered chopper and thoughts on how to incorporate a more car-like riding position led Gurney to build the first of his Alligators-the Al, a stretched Honda XL350 with a radically lowered seat. The machine showed promise, and as Gurney’s All American Racers grew into the premier manufacturer of Indycar chassis and then the builder of Toyota GTP cars, the development of a recumbent sportbike continued from Al to A6, the current version of the Alligator.

CYCLE WORLD TEST

As was the first Alligator, the latest is built around a Honda engine and components. Its engine was borrowed from an XR650L, complete with electric starting. All American Racers didn’t get its name for nothing, though. For the Alligator, the engine has become almost as much Gumey as Honda, more racer than enduro. Piston size has increased to a mammoth 104.8mm, working with the 82mm stroke to yield 708cc. The cylinder head has passed through milling machines, receiving all-new, separate, downdraft inlet ports. It no longer breathes through a Keihin carburetor, but instead has twin trumpets of a Pectel fuel-injection system poking up high. More aggressive cam timing is used, and the compression ratio has been set at an impressive 12:1. A long, Buell-like muffler (not that it actually muffles) rides under the engine.

The chassis carrying the engine comes largely from Gurney’s Santa Ana, California, facility-a large, impressive factory with its own wind tunnel and huge autoclave, and one that has the capabilities of manufacturing anything from a Formula One chassis to small military aircraft that can’t be talked about. A specially designed, straight-tube, spaceframe wraps around the engine. Beautifully made carbonfiber bodywork positions an airbox above and slightly behind the engine, while the gas tank is largely under the rider’s seat. A 60-inch wheelbase and a forward location for the narrow Single allow the rider to be set just in front of the rear tire, only 18 inches above the ground!

Stop and consider that dimension for a second. With the average sportbike seat up around 32 inches, and the lowest cruisers having seat heights in the 26-inch range, the Alligator places its rider closer to the ground compared to a low-riding Harley than the Harley does compared to a sportbike. There are a lot of cars that have higher-mounted seat cushions than does the Alligator. The entire machine was designed around that height, with components carefully chosen to achieve it. The short engine makes room for the rider without having the wheelbase stretch out to infinity, and is narrow enough that the rider’s legs can comfortably wrap around it. The footpegs mount forward of the engine, their inner surfaces actually inboard of the engine cases. A 6-foot rider sits low on the seat, his feet far forward, his heels close to the centerline of the bike, his knees splayed out slightly and bent. The handlebars are almost at shoulder height, a slight reach forward. As you take hold of the grips, your back takes a natural curve, and there’s actually a seat back to support it.

The light engine and the racecar-quality chassis make for a very light motorcycle: only 340 pounds full of gas. While the center of gravity of the Alligator itself isn’t that much lower than that of other motorcycles (only the fuel and battery are appreciably lower), the center of gravity of the Alligator and its rider combined are substantially lower. A typical rider masses half as much as the Alligator, and is positioned almost 14 inches lower than he would be on a conventional sportbike. That’s enough to drop the overall center of gravity by several inches.

A low center of gravity and a slightly long wheelbase offer predictable effects: The combination reduces weight transfer during acceleration and braking.

Neither wheelies nor stoppies are readily in the Alligator’s bag of tricks.

Instead, there’s just the right balance between weight transfer and tire traction to produce outstanding dragstrip launches. Assisted by its relatively heavy flywheels and 60-plus rearwheel horsepower output, the A6 sprinted from a stop to 30 mph in just

1.1 seconds-quicker than any other streetbike CW has ever tested. A few 150-horsepower bikes have produced better 0-60 times than the Alligator’s

3.1 seconds, but nothing with a comparable power-to-weight ratio has come close. Similarly, the braking performance of the Alligator was outstanding: the 30-mph stopping distance was just 27 feet, and the 60-mph stop took only 114 feet. The low seat height also dramatically reduces frontal area, producing desirable aerodynamic results. That explains how it’s also the fastest street-going Single that we’ve seen, with a top speed of 133 mph.

But perhaps the most notable characteristic of the Alligator is the predictability of its handling. According to Gurney, he wanted a bike that didn’t send any subtle, subjective messages that all wasn’t well, that you should be careful even though you were a long way from traction limits. Through the years of development leading to the A6, he achieved his result. On a tight backroad, you can lean the Alligator into a comer easily and lightly, and then just steer anywhere you want to go, changing your line (or not) at a whim. If the comer tightens, a slight counter-steering motion leans the bike in further, surely and certainly. You can brake leaned over, and the steering is almost unaffected. In a series of esses, the Alligator can be flicked from side-to-side readily and quickly. You’ll find yourself adjusting to the unique riding position in the first few miles, and after that, it’s almost all smiles. According to Road Test Editor Don Canet, the easy maneuverability and precise steering remind him most of the classic Thumpers on narrow tires that he’s ridden in vintage races; he can’t think of another machine with the wide modem tires of the Alligator that feels similar.

There are a few tricks to be learned. The Alligator works best if you keep your heels high on the pegs. That way, your feet don’t touch down even at extreme lean angles. And, while you can go very fast fixed in place on the seat, the A6 does respond to hanging off-or in this case by scrunching your butt sideways to shift your weight to one side or the other. It’s harder to do than on a conventional sportbike with the pegs directly under you, but it is a skill mastered by the riders who’ve developed the Alligator.

Finally, you’ll find that while the Alligator is marvelously linear during even aggressive street riding, its performance starts to unravel slightly as it approaches the edge. Most noticeable is a slight rear shuffle under very aggressive cornering that is perhaps related to the very low 23-psi air pressure recommended for the big 180-section rear tire.

Meanwhile, the engine of the Alligator is almost as notable as the chassis. Up to this point, Gurney has made no effort to make the Alligator comply with sound laws, and its big Single bellows like a Ron Wood dirt-tracker, which is to say it’s loud indeed for the street. Gearing is tall, and the A6 pulls smoothly from 3500 rpm or so. At 4500, it leaps up into its powerband, reaching almost 50 foot-pounds of torque at 6500 rpm, and 65.4 horsepower at 7700 rpm-with the airbox removed. With the airbox in place, power dropped to just over 60 horsepower, and development work on both silencing and airbox design continues. But on the street, the Alligator accelerates hard and feels noticeably torquey and strong; there’s no production Single that runs anywhere near as well. Honda’s counterbalancer reduces vibration to an unobjectionable level over the lower 80 percent of the operating range; it’s only as you run toward 8000 rpm that the machine gets buzzy.

Will the Alligator revolutionize motorcycling? That’s unlikely. Feet-forward bikes have had their proponents for

years, and any historian of motorcycling can point to machines such as the 1920s Neracar or the more recent English Quasar as examples of the type. And the balance between wheelbase length, polar moment of inertia, center of gravity height and riding position that has been found suitable for racing isn’t really threatened by the Alligator. Gurney readily admits that the Alligator hasn’t set any lap records even on tight courses, and that the primary benefits it offers are comfort, aerodynamics and the predictability of its handling for a normal street rider.

But the Alligator is a project that Gurney has pursued not for financial gain, but because of his passion. A first batch of 36 similar to the A6 tested here is coming at a price of $35,000 apiece. That might be fearsomely expensive by some standards, but it’s almost certainly cheap compared with the cost of manufacture. The production versions will almost assuredly see some revisions to intake and exhaust systems to comply with regulatory requirements. (Perhaps the barely muffled setup

tested here will become the “off-road” kit). Meanwhile, Gurney dreams of producing versions with far more powerful, American-designed multi-cylinder engines, and of a future where machines utilizing the design and principals behind the Alligator take their place alongside other configurations as a normal part of the motorcycle universe. For a man who remains the only American to have won a F-l race with a car of his own manufacture, that’s not too impossible of a dream.

ALLIGATOR

A6

$35,000

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Other Side of Speed

November 2002 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsA Morning In Italy

November 2002 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCLiving In Harmony

November 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

November 2002 -

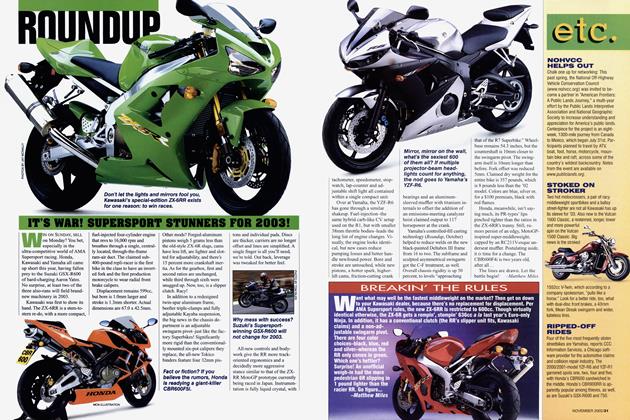

Roundup

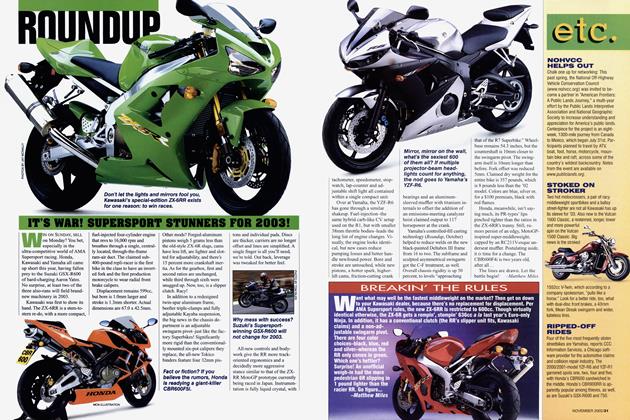

RoundupIt's War! Supersport Stunners For 2003!

November 2002 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupBreakin' the Rules

November 2002 By Matthew Miles