Powering up

TDC

Kevin Cameron

DURING THE 1950S AND ’60S, MOTORcycles that won 500cc GP roadraces did not have to use much more than 50 horsepower worth of tire to do so. Why not? The only real opposition faced by the four-cylinder Italian Gileras and MVs of that era were 50-bhp privateer Norton and Matchless Singles.

Tires advanced in that time from prewar cotton-carcass bias construction to thinner and much stronger, coolerrunning nylon and rayon carcasseswith little size increase. Tread advanced from snappy natural rubber to more hysteretic natural-synthetic blends that gave greater grip, especially in the wet. Rim size was measured in “WM” units (no one I’ve ever asked knows what a “WM” is), the largest available for rear tires being a WM3, which measured 2.15 inches between the flanges. Compare that with today’s 6.25 inches. When I pick up one of those skinny early rims today, it seems like a bicycle part.

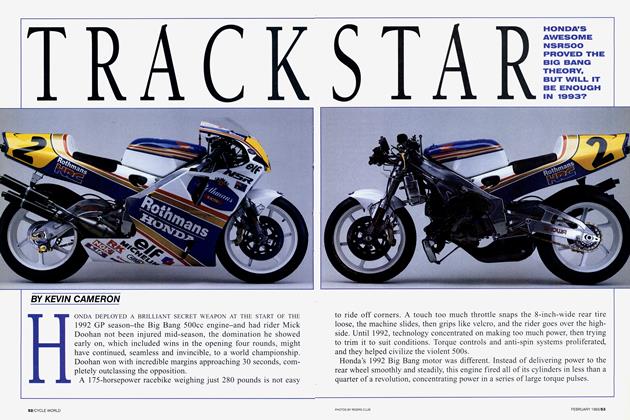

Real 500cc racing resumed when Honda entered the class in 1966. Would Honda’s magisterial formula of horsepower through rpm knock over that class as it had the 50, 125, 250 and 350cc classes? Suddenly, 500 tires became a hot subject, as in 1967 Mike Hailwood on the Honda Four and Giacomo Agostini on the MV Three actually raced—and hard!

When big-bike horsepower jumps, interesting new things happen. In this case, Honda’s nearly 90-bhp RC181 was a big step up on the MV Despite high power claims from a decade of beautiful, blaring, red Italian Fours, historical skepticism suggests that all they needed to keep the Singles in their place was about 60 bhp. That year did not, however, turn out to be a clawing, scratching battle of raw power between Honda and MV Something new showed its head. On acceleration tracks, the Honda’s rearward weight bias provoked instability that even Mighty Mike couldn’t master. This turned the Honda’s throttle into a weave selector-a little was bad, more was worse and the throttle opening he needed to be first out of the corner was often downright impossible. The more stable MV, with its less powerful engine mounted nearer the front, showed that less can indeed be more.

Dunlop, expecting a desperate Honda-MV battle in 1968, prepared a special larger tire and wider rim to handle the new horsepower. The tire was called 3.50M, a tall-sidewall variant of the previous 3.50 x 18 rear tire. Its increased flexibility acted like a lateral damper, taking energy out of the weave motion that had horrified 1967 race-goers. The new rim was called WM4 and was supplied blank-undimpled and undrilled. It measured 2.5 inches between flanges.

Unfortunately, in 1968 the 500 Honda went to a museum instead of the track, and the 3.50M wasn’t used until 1971, when the Kawasaki 500s needed it. The next step up in power didn’t happen until 1972, when Kawasaki and Suzuki came to Daytona with 100-plus-bhp 750s. These bikes ate their tires instead of the opposition, leaving little Yamaha 350 Twins to win on old-tech tires. To paraphrase Pomeroy, “The first instance of novel principle is invariably defeated by the proven product of established practice.”

As tire men looked on in dismay, horsepower rose relentlessly. Dunlop replied in 1974 with its pioneering wide, “flattened-round” profile super-speedway tire, to be mounted on a rim that looked impossibly wide to us at the time. Still using the arcane WM system, this was a WM5, or 3 inches across. Goodyear then launched the slick era, and the WM measuring stick came to an end with the 3.5-inch-wide WM6.

Two-stroke 500cc GP bikes appeared in 1973-74 at the 90-bhp level, but every time someone fiddled with a port height or direction, another 5 horsepower appeared. By 1981-82, power was at 135 bhp and even a giant bias rear tire that measured 8 inches sidewall-to-sidewall was done for in 7-10 hard laps. After a couple of years of largely fruitless head scratching, the tire world gave up bias construction and adopted Michelin’s radial-based carcass construction. Now rims grew like horsepower, ceasing only when the FIM imposed the present limit at 6.25 inches between flanges.

GP two-stroke power hit the 200-bhp mark and the combination of a 286pound weight limit and the 6.25-inch maximum rear rim seemed to define a performance plateau.

Change continues, because starting this year 990cc four-strokes race with the 500cc two-strokes-all on 6.25 , rims. So far, there is no sign of any f tire crisis of the kind that hit in ■J 1967, 1972 or 1980-84. Tire engineers seem to feel that the giant new four-strokes, despite their being 30-50 peak horsepower stronger than the twostrokes, are if anything a bit kinder to tires. That makes sense because fourstroke throttle-up is more like a ramp while the two-stroke’s natural response is a step. If an engine is smooth, its rider can more closely match throttle to available traction and accelerate harder without sudden outbreaks of wheelspin. Tires like smoothness.

What new towers of rubber will the tiremakers build on that (now) modest 6.25inch foundation? Back in the days of the Dunlop Triangular 3.50 x 18 rear, the rim was only 2.15 inches wide, but the tire, measured shoulder-to-shoulder, was about twice as wide. If a similar cantilevering of the tire became possible today, it could result in rear tires a foot wide instead of the present skinny 8 inches.

So far, GP tire design’s response to the 990cc horsepower jump has been modest. Some tires of larger rolling diameter have been built for 16.5-inch-diameter rims. If tires actually do outgrow rims, it will bring increased turn-in and steering difficulty, as the front tire, acting on the wheelbase as lever, must twist the large rear footprint against the pavement. Why not larger fronts to steer larger rears? For years, we’ve been told fronts can never grow because it’s so hard to build quick steering and good behavior into larger fronts. Never? I’ve been hearing never all my life, but there’s been a lot of change. There will be a lot more.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontState of the Streetbike

August 2002 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsBack In the Dez

August 2002 By Peter Egan -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

August 2002 -

Roundup

RoundupBmw To Motogp?

August 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupFour-Cylinder Triumph Daytona?

August 2002 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupGurney 'gator Ready To Roll

August 2002 By Brian Catterson