TDC

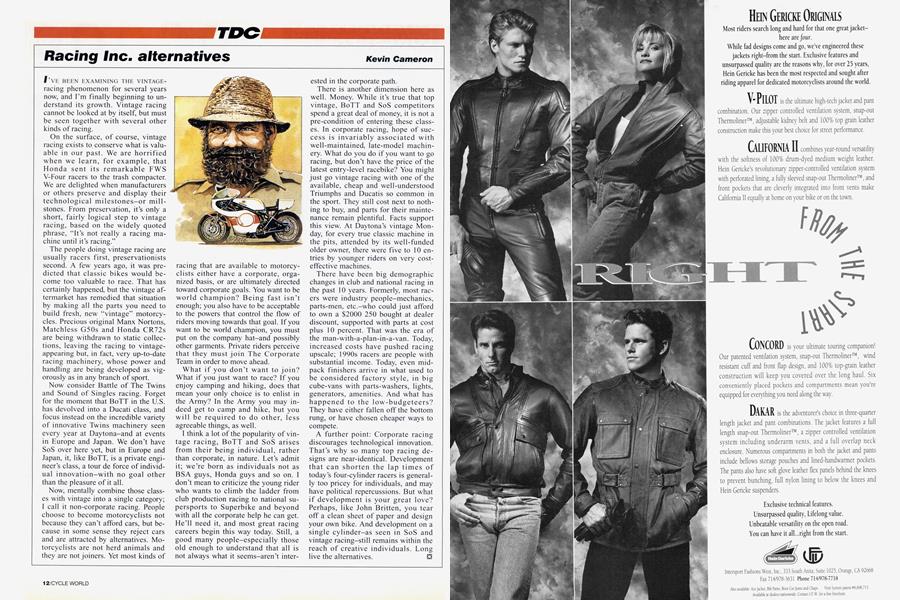

Racing Inc. alternatives

Kevin Cameron

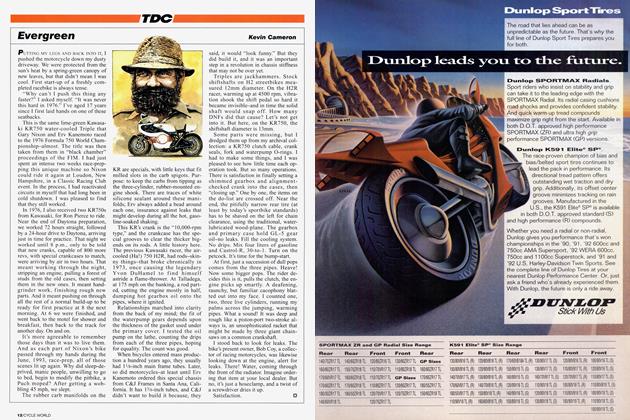

I’VE BEEN EXAMINING THE VINTAGEracing phenomenon for several years now, and I’m finally beginning to understand its growth. Vintage racing cannot be looked at by itself, but must be seen together with several other kinds of racing.

On the surface, of course, vintage racing exists to conserve what is valuable in our past. We are horrified when we learn, for example, that Honda sent its remarkable FWS V-Four racers to the trash compacter. We are delighted when manufacturers or others preserve and display their technological milestones-or millstones. From preservation, it’s only a short, fairly logical step to vintage racing, based on the widely quoted phrase, “It’s not really a racing machine until it’s racing.”

The people doing vintage racing are usually racers first, preservationists second. A few years ago, it was predicted that classic bikes would become too valuable to race. That has certainly happened, but the vintage aftermarket has remedied that situation by making all the parts you need to build fresh, new “vintage” motorcycles. Precious original Manx Nortons, Matchless G50s and Honda CR72s are being withdrawn to static collections, leaving the racing to vintageappearing but, in fact, very up-to-date racing machinery, whose power and handling are being developed as vigorously as in any branch of sport.

Now consider Battle of The Twins and Sound of Singles racing. Forget for the moment that BoTT in the U.S. has devolved into a Ducati class, and focus instead on the incredible variety of innovative Twins machinery seen every year at Daytona-and at events in Europe and Japan. We don’t have SoS over here yet, but in Europe and Japan, it, like BoTT, is a private engineer’s class, a tour de force of individual innovation-with no goal other than the pleasure of it all.

Now, mentally combine those classes with vintage into a single category;

I call it non-corporate racing. People choose to become motorcyclists not because they can’t afford cars, but because in some sense they reject cars and are attracted by alternatives. Motorcyclists are not herd animals and they are not joiners. Yet most kinds of racing that are available to motorcyclists either have a corporate, organized basis, or are ultimately directed toward corporate goals. You want to be world champion? Being fast isn’t enough; you also have to be acceptable to the powers that control the flow of riders moving towards that goal. If you want to be world champion, you must put on the company hat-and possibly other garments. Private riders perceive that they must join The Corporate Team in order to move ahead.

What if you don’t want to join? What if you just want to race? If you enjoy camping and hiking, does that mean your only choice is to enlist in the Army? In the Army you may indeed get to camp and hike, but you will be required to do other, less agreeable things, as well.

I think a lot of the popularity of vintage racing, BoTT and SoS arises from their being individual, rather than corporate, in nature. Let’s admit it; we’re born as individuals not as BSA guys, Honda guys and so on. I don’t mean to criticize the young rider who wants to climb the ladder from club production racing to national supersports to Superbike and beyond with all the corporate help he can get. He’ll need it, and most great racing careers begin this way today. Still, a good many people-especially those old enough to understand that all is not always what it seems-aren’t interested in the corporate path.

There is another dimension here as well. Money. While it’s true that top vintage, BoTT and SoS competitors spend a great deal of money, it is not a pre-condition of entering these classes. In corporate racing, hope of success is invariably associated with well-maintained, late-model machinery. What do you do if you want to go racing, but don’t have the price of the latest entry-level racebike? You might just go vintage racing with one of the available, cheap and well-understood Triumphs and Ducatis so common in the sport. They still cost next to nothing to buy, and parts for their maintenance remain plentiful. Facts support this view. At Daytona’s vintage Monday, for every true classic machine in the pits, attended by its well-funded older owner, there were five to 10 entries by younger riders on very costeffective machines.

There have been big demographic changes in club and national racing in the past 10 years. Formerly, most racers were industry people-mechanics, parts-men, etc.-who could just afford to own a $2000 250 bought at dealer discount, supported with parts at cost plus 10 percent. That was the era of the man-with-a-plan-in-a-van. Today, increased costs have pushed racing upscale; 1990s racers are people with substantial income. Today, even midpack finishers arrive in what used to be considered factory style, in big cube-vans with parts-washers, lights, generators, amenities. And what has happened to the low-budgeteers? They have either fallen off the bottom rung, or have chosen cheaper ways to compete.

A further point: Corporate racing discourages technological innovation. That’s why so many top racing designs are near-identical. Development that can shorten the lap times of today’s four-cylinder racers is generally too pricey for individuals, and may have political repercussions. But what if development is your great love? Perhaps, like John Britten, you tear off a clean sheet of paper and design your own bike. And development on a single cylinder-as seen in SoS and vintage racing-still remains within the reach of creative individuals. Long live the alternatives.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue