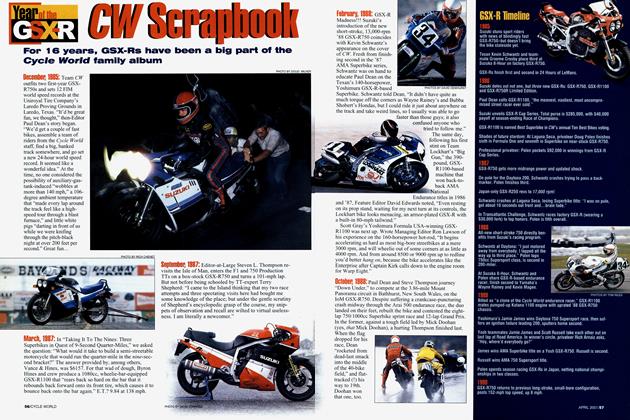

Genesis

Year of the GSX-R

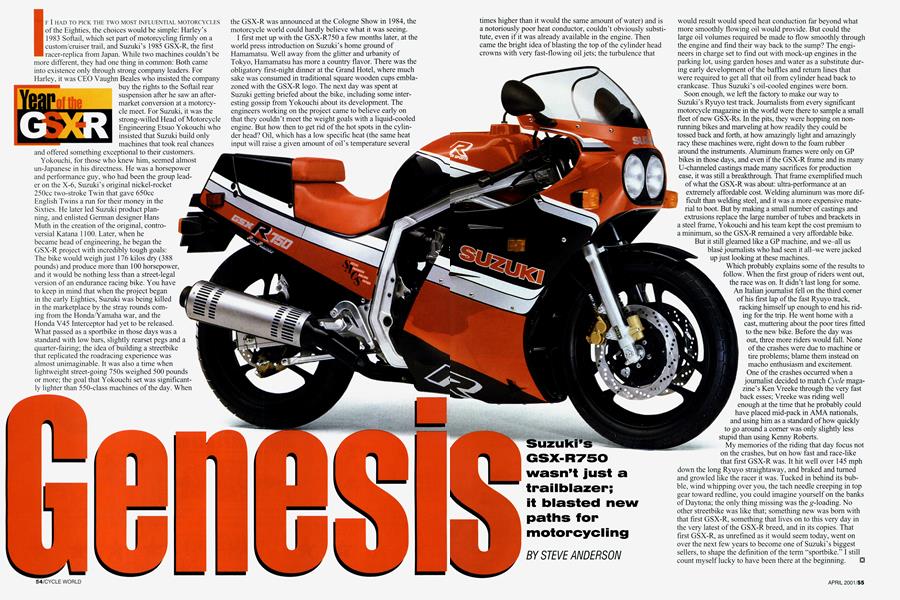

IF I HAD TO PICK THE TWO MOST INFLUENTIAL MOTORCYCLES of the Eighties, the choices would be simple: Harley's 1983 Softail, which set part of motorcycling firmly on a custom/cruiser trail, and Suzuki's 1985 GSX-R, the first racer-replica from Japan. While two machines couldn't be more different, they had one thing in common: Both came into existence only through strong company leaders. For Harley, it was CEO Vaughn Beales who insisted the company buy the rights to the Soflail rear suspension after he saw an after market conversion at a motorcy cle meet. For Suzuki, it was the strong-willed Head of Motorcycle Engineering Etsuo Yokouchi who insisted that Suzuki build only machines that took real chances and offered something exceptional to their customers.

Yokouchi, for those who knew him, seemed almost un-Japanese in his directness. He was a horsepower and performance guy, who had been the group lead er on the X-6, Suzuki's original nickel-rocket 250cc two-stroke Twin that gave 650cc English Twins a run for their money in the Sixties. He later led Suzuki product plan ning, and enlisted German designer Hans Muth in the creation of the original, contro versial Katana 1100. Later, when he became head of engineering, he began the GSX-R project with incredibly tough goals: The bike would weigh just 176 kilos dry (388 pounds) and produce more than 100 horsepower, and it would be nothing less than a street-legal version of an endurance racing bike. You have to keep in mind that when the project began in the early Eighties, Suzuki was being killed in the marketplace by the stray rounds corn ing from the Honda/Yamaha war, and the Honda V45 Interceptor had yet to be released. What passed as a sportbike in those days was a standard with low bars, slightly rearset pegs and a quarter-fairing; the idea of building a streetbike that replicated the roadracing experience was almost unimaginable. It was also a time when lightweight street-going 750s weighed 500 pounds or more; the goal that Yokouchi set was significant lylighter than 550-class machines of the day. When the GSX-R was announced at the Cologne Show in 1984, the motorcycle world could hardly believe what it was seeing.

I first met up with the GSX-R750 a few months later, at the world press introduction on Suzuki's home ground of Hamamatsu. Well away from the glitter and urbanity of Tokyo, Hamamatsu has more a country flavor. There was the obligatory first-night dinner at the Grand Hotel, where much sake was consumed in traditional square wooden cups embla zoned with the GSX-R logo. The next day was spent at Suzuki getting briefed about the bike, including some inter esting gossip from Yokouchi about its development. The engineers working on the project came to believe early on that they couldn't meet the weight goals with a liquid-cooled engine. But how then to get rid of the hot spots in the cylin der head? Oil, which has a low specific heat (the same heat input will raise a given amount of oil's temperature several times higher than it would the same amount of water) and is a notoriously poor heat conductor, couldn’t obviously substitute, even if it was already available in the engine. Then came the bright idea of blasting the top of the cylinder head crowns with very fast-flowing oil jets; the turbulence that would result would speed heat conduction far beyond what more smoothly flowing oil would provide. But could the large oil volumes required be made to flow smoothly through the engine and find their way back to the sump? The engineers in charge set to find out with mock-up engines in the parking lot, using garden hoses and water as a substitute during early development of the baffles and return lines that were required to get all that oil from cylinder head back to crankcase. Thus Suzuki’s oil-cooled engines were bom.

Suzuki's GSX-R750 wasn't just a trailblazer; it blasted new paths for motorcycling

STEVE ANDERSON

Soon enough, we left the factory to make our way to Suzuki’s Ryuyo test track. Journalists from every significant motorcycle magazine in the world were there to sample a small fleet of new GSX-Rs. In the pits, they were hopping on nonrunning bikes and marveling at how readily they could be tossed back and forth, at how amazingly light and amazingly racy these machines were, right down to the foam rubber around the instruments. Aluminum frames were only on GP bikes in those days, and even if the GSX-R frame and its many U-channeled castings made many sacrifices for production ease, it was still a breakthrough. That frame exemplified much of what the GSX-R was about: ultra-performance at an extremely affordable cost. Welding aluminum was more difficult than welding steel, and it was a more expensive material to boot. But by making a small number of castings and extrusions replace the large number of tubes and brackets in a steel frame, Yokouchi and his team kept the cost premium to a minimum, so the GSX-R remained a very affordable bike.

But it still gleamed like a GP machine, and we-all us blasé journalists who had seen it all-we were jacked up just looking at these machines.

Which probably explains some of the results to follow. When the first group of riders went out, the race was on. It didn’t last long for some. An Italian journalist fell on the third comer of his first lap of the fast Ryuyo track, racking himself up enough to end his riding for the trip. He went home with a cast, muttering about the poor tires fitted to the new bike. Before the day was out, three more riders would fall. None of the crashes were due to machine or tire problems; blame them instead on macho enthusiasm and excitement. One of the crashes occurred when a journalist decided to match Cycle magazine’s Ken Vreeke through the very fast back esses; Vreeke was riding well enough at the time that he probably could have placed mid-pack in AMA nationals, and using him as a standard of how quickly to go around a comer was only slightly less stupid than using Kenny Roberts.

My memories of the riding that day focus not on the crashes, but on how fast and race-like that first GSX-R was. It hit well over 145 mph down the long Ryuyo straightaway, and braked and turned and growled like the racer it was. Tucked in behind its bubble, wind whipping over you, the tach needle creeping in top gear toward rechine, you could imagine yourself on the banks of Daytona; the only thing missing was the g-loading. No other streetbike was like that; something new was bom with that first GSX-R, something that lives on to this very day in the very latest of the GSX-R breed, and in its copies. That first GSX-R, as unrefined as it would seem today, went on over the next few years to become one of Suzuki’s biggest sellers, to shape the definition of the term “sportbike.” I still count myself lucky to have been there at the beginning.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontRamblings, Rumblings

April 2001 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsRambling Roadblocks

April 2001 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCLet There Be Light

April 2001 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

April 2001 -

Roundup

RoundupHarley's Supercruiser Revolution

April 2001 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupVoxan On Track

April 2001 By Stephan Legrand