BEHIND THE BARRIER

RACE WATCH

Up close and personal with John Kocinski

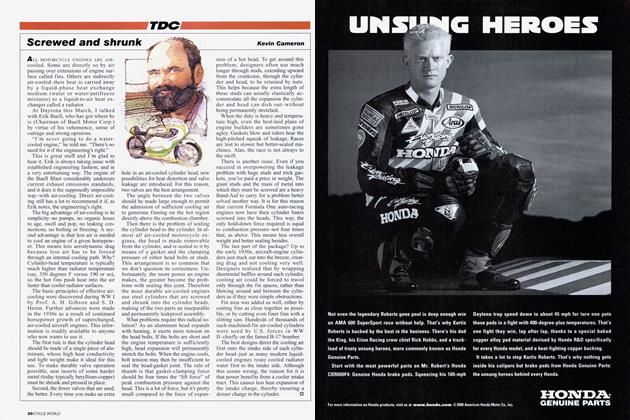

KEVIN CAMERON

"I MAKE PEOPLE NERVOUS,” JOHN KOCINSKI SAYS, STARING EARNESTLY into im my face. “I radiate energy. People can feel it.” Kocinski has just emerged from semi-retirement. Having not ridden a motorcycle in the nine months since his 1999 Grand Prix season finale on a Team Kanemoto Honda NSR500, he was “called up” to ride the Vance & Hines Ducati 996 in the AMA Superbike series. He replaces Troy Bayliss, who has taken Carl Fogarty’s place on Ducati’s World Superbike team. We were talking in the hushed, cool lounge of the V&H transporter at Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin. At the Road Atlanta round, one week before, John had begun by finishing seventh in the first race and fourth in the second.

Kocinski is not like other riders. His intensity is painful. He does make people nervous because his emotions are on the outside, not the inside. He is mysterious and unpredictable, but he is also emotionally naked. Whatever he feels, you feel.

When 1 asked him if there was a time when I could speak to him at length, he was sitting at trackside, race-face installed, waiting to go out to practice. His answer? “Next year.” Then he said, “After the race. Come to the truck.” 1 left him with his responsibilities.

Elkhart now runs a two-race format. There would be races on Saturday and Sunday, with very little practice time. In Saturday’s race, there was a red flag on lap one. V&H teammate Steve Rapp touched the back of John’s bike with his brake lever entering Turn 1. Rapp’s bike flipped, bounding off the track, breaking into pieces. Rapp was unhurt.

Kocinski led off the line at the restart, smoothly pulling away from the top AMA stars, and for seven laps thereafter. Then he slowed, backsliding to a fourth-place finish, with his bike overheating badly in the final three laps. 1 went to the truck, but no John. Shortly, team owner Terry Vance emerged, on his way somewhere. I told him I’d come to talk to John.

“I don't think so!” he replied. “He’s hopping mad because the bike let him down, and he’s in his motorhome at the top of the hill. You can go knock on his door if you like.”

I walked up there and found the address, revealed by the red V&H pitscooter parked in front. Tossed on the pavement were John’s leathers and boots. Bad time! That morning, 1 had talked to people who had dinner with John the night before. Their impression was that he was just doing this gig for fun, that he was above life’s little struggles now, a senior figure. Ha! Don’t bet on it. I returned to the truck. When 1 described the tossed leathers and boots to V&H crew chief Jim Leonard, he replied with characteristic understatement: “He wants to do good.”

In time Kocinski appeared, and he was gracious, making sure to thank each of his mechanics, then getting me a drink and excusing himself to go talk tires “for 10 minutes” with Dunlop technician Jim Allen. This was fine with me-I’d rather tell my editor there was no story than get in the way.

On his return, John marched back into his post-race debriefing, announcing first that he’d gotten another tire-one that was supposedly unavailable-for Sunday’s race. Looking around at everyone, he repeated the words, “The power of negotiation,” twice for emphasis. Then, he launched straight into his mental do-list, beginning with a cryptic query about rearrim width, “Five-seven-five?”

“That’s little,” replied Leonard. “Yeah, but I always burn up the tire

on those wide rims. Anyway, Kevin’s here to talk to me. He doesn t want to hear this stuff.”

“He loves it,” said Jim, arranging the papers on his clipboard.

And so, standing in the doorway of the little gray corduroy cool room, I got to hear these superprofessionals go through their business. For them, it’s routine-the bricks and mortar of their days. For me, it was a wonderful snapshot-John and Jim proposing and disposing, with both an Italian and an American mechanic contributing, and Vance silently taking it all in. I was the fly on the wall. “Can I get some wheelbase?” “No. Not unless you can stand a tooth off the back.”

The Ducati, with its swingarm pivot a part of the engine cases, its chain tension adjustment on an eccentric and its short swingarm length, is one of the most tightly compromised designs in Superbike racing. Changing one thing means changing everything.

“One tooth,” Leonard continued. “If you’re not revving it real hard you might get away with it.” “How much more?” “Three hundred rpm.”

“Can you change the internal ratios to get it back?” “Nope.”

Extra wheelbase would slightly increase front-wheel load-and might make steering on the front wheel more practical.

Earlier, rear spring rate came up. “The back of the bike’s wallowing up and down,” John said, making the motions with his hands. “What’s that?”

“Too stiff,” offered the Italian.

“Can we go lighter? Ten-eight (spring)? Anyway, I don’t care if it’s wobbling around, as long as it’s turning. It can wobble all it wants-I need it to turn.”

Kocinski’s style has always been to steer with the front wheel-as he learned to do so brilliantly in his early years on Bud Aksland’s Yamaha TZ250s. But the acceleration of big bikes unweights their front tires, making front-steer difficult. Therefore most successful 500cc GP and Superbike riders steer with the throttle, through controlled wheelspin. This is not John’s style-although he did it when necessary en route to winning the ’97 WSB title on the Castrol Honda RC45.

Jim said, “Did you look at your tire? It’s not nearly shagged.”

This means: You can use it harder. Spin it, even. I couldn’t resist saying, “The tuner tunes the bike, the rider tunes the tuner, and around it all goes.”

“Kevin has some pretty weird ideas,” John said to the ceiling.

“John’s pretty weird himself,” Jim put in, passing on the ribbing. “His mind is a strange little room.”

As the discussion continued, each point covered revealed more clearly that John wanted the machine to steer his way, and Jim wanted John to accept that Ducatis don’t make that easy. The Ducati, with one of its two 90-degree cylinders horizontal, has its engine mass significantly farther back in the chassis than does an inline-Four. Finally, both men ran out of words, and simply stared at each other across the small space, each one silently radiating his own thoughts. I thought of an earlier cryptic remark of John’s: “I have to be able to see through steel.”

Later, talking to Jim alone, I asked if he thought the Ducati could only be steered Anthony Gobert’s way, on the throttle.

“No, I keep an open mind. We’ll get it. It’ll just take time.”

The week before, in Atlanta, practice had been a madhouse of rapid-fire changes to get the riding positionpegs and bars and seat-to where John needed it. Ducatis steer as well as they do because their powerband has been smoothed to eliminate torque surges that could upset the front tire’s grip. ExDucati rider Pier-Francesco Chili, now with Suzuki, used high comer speed to make acceleration less necessary, but it is speed onto the next straight that’s needed. Speed at the apex is not the same as speed off the comer. The coming of the Honda RC51, which is like an intensified Ducati, is magnifying the faults of the original-one of which is touchy front grip.

Speaking of the two-race format, Vance said, “The pace is too quick. We’ll get something here (in terms of a useful setup), but next weekend at Loudon, we won’t have anything, and we’ll have to do it all over again. Did you see John’s race? He’s so smooth, he doesn’t even look like he’s going fast.” The discussion in the transporter continued. “Ten-five,” Kocinski said. “That’s what it’s gotta be tomorrow (the lap time2:10.5). A lot of things have to change to make that happen.”

“The leader’s average lap was 2:11.7,” commented Leonard. Big difference.

“That bike I rode today isn’t going to do it. We have to find something that’ll work.”

When the invisible checklist was finished, John and I were left alone.

“Well, what do you want to ask me?” John began.

I told him that our readers’ letters and e-mails show that they regard him as the misunderstood genius of roadracing. How does the misunderstanding happen?

“Neil Tuxworth (Castrol Honda team manager) knows how to run a race team,” he began. “He knows that riders need certain things to go fast. He either sees to it that they get what they need, or he makes a sincere effort. A visible, sincere effort. He does things right. They have the people.”

How about the Spanish team? (Kocinski rode Sito Pons’ Movistar Honda NSR500 in 1998, and somehow never hooked up-despite the fact that he made it clear that getting back on a 500cc GP bike was his real goal.)

“I speak English. I need to work with a team that speaks English-like the Castrol team.”

How about Erv? (Last year, Kocinski rode Kanemoto’s NSR, again with disappointing results.)

“I still have his sticker on my helmet. I ride with it. I called him up, said I was going racing again.”

But was there a specific problem?

“Money. There was never enough money.” Kocinski said this with clear regret-he obviously respects Erv very much. No money means no parts, no test dates-maybe even no results. Erv’s teams are like promising little colleges with great professors and no endowment.

An Arai helmet technician poked his head in the door, offering a freshly painted helmet with duct-tape-tabbed tear-offs already in place. After a brief exchange over this, John turned to me and said, “That’s what I like. Things that are done exactly right. This helmet is perfect. Perfect.”

He was silent for a moment, then said, “I need to work with people who believe in me. I expect help. When I say there’s something wrong with the motorcycle, there’s something wrong with it.

When that gets fixed, I go faster. I have to work with people who believe in me.”

“Then once a rider finds the right engineer or crew chief to work with, he should take that person with him wherever he rides?” I asked.

“Yes! Because once they stop believing in you...”

Kocinski clearly wasn’t in that situation at the moment-Vance and Leonard both say they believe John will pull away once they work through to a setup for him. But the not-believing situation is one I’ve seen more than once, and John knows how quickly confidence turns into its opposite.

“I can ride a motorcycle. I haven’t reached that point (of declining skills). I ask a lot from myself, and I expect a lot from the people around me. If I’m working out, getting in shape and somebody on my team comes up and says, ‘Hey, you’ve gotta work harder,’ that’s okay, my feelings aren’t hurt-I’ve gotta work harder. So if I say the same thing to people on my team, it’s just the truth. I don’t want to hurt anybody’s feelings, but if something’s wrong, I want somebody to know it.”

Sunday morning would give only 10 laps of practice time. Of this, three laps would be needed to check out the replacement engine freshly installed in the Saturday bike. To get maximum

test time, a second bike, with new experimental settings, would be warmed up and waiting at the pit wall,

If this were a novel, the experiments would solve everything and lead to a spectacular win on Sunday. After all, Ducatis have won this event the past four times. But making a fresh marriage of a man and a machine is not a literary problem.

Here is a worst-case scenario: When a new rider replaces a departed champion-as Daryl Beattie did at Suzuki when Kevin Schwantz retired-he tests the machine and requests changes in its setup. Team engineers look at each other knowingly. Change perfection? No waythey know the answers. Therefore, the new man’s requests are either ignored or only partly answered. Unable to make the lap times, the new rider does the only thing he can do-he rides harder. On an unfamiliar bike, which responds to him in strange ways, this is risky. He crashes.

This scenario isn’t happening to John Kocinski, but he knows it can. It’s not happening here because of the professionalism of Jim Leonard, and because John makes the bike go faster when specific problems are fixed. As he said, racing success is about people.

In Sunday’s race, series points-leader Mat Mladin, his Yoshimura Suzuki teammate Aaron Yates, and eventual winner, Honda-mounted Nicky Hayden, had a frighteningly intense battle,

while Miguel Duhamel and Kocinski, who again led briefly, ran nose-to-tail some distance back for fourth and fifth. Kocinski was running his bike right to the edges of the track (even posting the quickest lap of the race, a 2:10.071) but was unable to launch himself past Duhamel to move ahead. The power is there. The turning, so far, is not.

Leonard’s comment was, “If you can’t get onto the straightaway here, you’re done.” That means making the bike turn while accelerating hardsomething that’s not possible with the current setup. Progress requires testing, and testing is scarce mid-season.

Leonard continued, “We talked about going with something new (on Sunday). I couldn’t say it’d be better for sure, but I was pretty sure. So in the end, we went with the conservative choice (basically, Saturday’s known setup). We’ve made progress. It doesn’t show in the results, but it’s real. This is a completely different motorcycle from what we started with in Atlanta.”

Reality is more interesting than a novel. Racers must above all be conservative, because the job is to get points. That means finishing races with the best-known setup, not gambling on novelties and then either having to override the problems or running slow. Yes, the experimental setup might have been better, but the risk of its not being better made it a bad play. Some programs “come good” very quickly, as Honda’s RC51 has done. Others take months or years-as Suzuki’s recent GSX-Rs or Honda’s RC45 did. Setup is about rider confidence, and it’s the hardest problem in motorcycle roadracing. To jump into a war fought by factory teams absolutely cold and get seventh-, fourth-, fourthand fifth-place finishes is a high achievement. In the weeks to come, Kocinski and his Vance & Hines crew will work hard to make the bike work for him. Like others before them, they will either succeed or fail.

Bostrom’s back

Eric Bostrom grew up riding dirtbikes the way the rest of us grew up breathing air. By the time he was old enough to enter races, he had the machine control to take care of business. When he joined the factory-backed American Honda team in mid-1998, he immediately won two AMA Superbike races on the hardto-master RC45 V-Four. The future looked bright.

Then, following an ankle-breaking crash at Daytona last year, Bostrom fell into a slump. By season’s end, he was out of a ride. When Kawasaki took its roadracing program in-house last fall, Bostrom was hired to team with grand master Doug Chandler. Early season Superbike outings were undistinguished. Then, at Road Atlanta, Bostrom fought his way forward to a fourth and a fifth by persistent, hard riding. More of the same at Road

America, where Bostrom finished third and sixth. Something had changedthings were looking up.

The following week, at Loudon, New Hampshire, Bostrom set fast time in Friday qualifying. On Saturday morning, I went to Al Ludington, one of Eric’s mechanics, and asked if he could arrange an interview.

“How ’bout now?” AÍ asked, leading me to the gleaming Kawasaki transport trailer. Bostrom was sitting at a table in the air-conditioned lounge, eating a ripe avocado with a plastic knife.I asked him how he’d overcome whatever was holding him back last year.

“I grew up riding dirtbikes, but any time I was on a roadrace bike, it was pressure. That took the fun out of it because I was like, ‘Kill!’ all the time. On this team, they’ve given me a ZX6R and said, just ride it and have fun. So I take it up to Willow Springs or wherever and do wheelies or get the back end loose, just have a good time.” Bostrom tries to smile or at least grin as he talks and, although he is a big, strong person, this gives him a charming boyish innocence that clashes wonderfully with the seriously fast lap times he’s now doing. Maybe a rider doesn’t have to look like a warweary GI to go fast.

I asked what is working now to give him quicker times.

“I’m much more aware of where the time is, how much time I can make in each place on the track,” he answered.

I asked how he was getting along with setup, which has always marked the big difference between the fun rider and the professional. Chassis and suspension setup are essential to rider confidence, but achieving a good setup is a technical operation.

“Where the RC45 was really kind of set-you didn’t change much-on the Kawasaki, everything’s adjustable.” So you can get lost? “Yes, and we did,” he grinned.

Then, he gave me an example: “When I was braking and it wanted to lift up (the rear wheel) real bad, we pushed the front end way out to stop it. And that made it so I couldn’t steer it in the corner.”

He went on to give more examples, noting that a major strong point of the Kawasaki is its quick turn-in. There is a price paid for making a bike this responsive, he observed, and that is instability. >

“If you let it, it’ll start ‘pumping’ (rider-speak for high-speed weave), and then you’re lost-you have to let the bike settle down before you can do anything with it. So you have to control that.”

How?

“I rode almost the whole Daytona 200 in a half-sit, my weight all on the pegs,” he replied.

Bostrom’s bike displayed instability in pre-Daytona testing, and he worked out this way of controlling it-without sacrificing the quick steering. In effect, he had de-coupled his body from the bike, making himself into a damper to control the motion of the machine.

There is an exact parallel with aircraft stability. If you make an airplane stable enough to fly hands-off, it’s too stable to respond instantly when you try to maneuver it. But if you speed up its response to make it maneuver quickly, it’s upset by every little gustclose to uncontrollable. Modern fighter aircraft have electronic systems to provide stability artificially. In the case of the Kawasaki, the stability system is Bostrom.

Back to Loudon. I asked if the Kawasaki steers easily with the throttle.

“Yes, especially in the last left-hander before reentering the infield. You can tighten your line.”

What is the key to going fast at Loudon?

“Getting good drives off the corners-especially the ones that lead onto a straight.”

After our conversation, I went to Turn 12, a first-gear left where riders exit the infield across a pavement transition, onto the short main straight. Bostrom was well off his bike to the inside, his upper body almost horizontal, and next to-not on top of-the machine. He was doing everything he could to push the bike upward early, getting the rear tire off its tender sidewall and up onto the flatter, higher-grip part of its tread surface. Two weekends before, he said to his mechanics, “These other guys are really snapping their bikes up off the sidewalls-I’ve got to start doing more of that.” And so he has.

Moments later, Yoshimura Suzuki’s Aaron Yates came by, accelerating off the same turn. As his back tire began to spin, his Suzuki started “pumping,” its engine note warbling. Instantly, he inclined his head forward and pushed his body away from the bike. The spinning and weaving stopped, and the bike shot hard off the turn. Other riders accelerated sitting up, making little attempt to lift their tires off the sidewall. Their acceleration suffered. I thought of how hard it must be to hold your body in the place physics wants it, as the bike’s acceleration tries to pull your arms straight, and still steer precisely. Knowledge, strength, stamina and concentration are required here.

Eric Bostrom learned these extraordinary skills as part of growing-up fun and natural observation. Now, he has put that fun-and the skills with it-back into his career.

-Kevin Cameron

Lampkin unstoppable

Dougie Lampkin is killing ’em. The 24-year-old from Yorkshire, England, has won the last four world indoor trials titles and is on course to score a fourth-consecutive outdoor crown. With three rounds remaining, “Our Dougie,” as he is universally known in the British trials world, leads Montesa teammate Takahisa Fujinami by a seemingly insurmountable 63 points.

Lampkin doesn’t just win championships; he wins them by the greatest possible margin. “I ride to win,” he said. “I never, ever take the safe option. I hate being beaten, but you never get tired of winning. I don’t, anyway!”

Lampkin’s superiority comes as a bit of a shock. Just three years ago, when the great Jordi Tarres retired after having amassed seven world titles, everyone said, “No one will ever dominate the sport like Jordi!”

At the time, Lampkin had already won one championship. Now, it appears Lampkin could easily win seven on the trot-indoor and outdoor-and he would be only 27 years old! Lampkin may not have Tarres’ on-bike creative genius, but he has a tremendous appetite for practice and an almost frightening capacity for intense concentration.

Lampkin comes from one of the most famous motorcycling families in England. His uncles, Arthur and Alan, were motocrossers and international trials aces, while dad Martin was the firstever world trials champ on a Bultaco back in 1975. Doug’s cousin John is the Beta importer, and this goes a fair way toward explaining why Doug had never ridden any other brand professionally. Until this year, when he shocked the trials world and switched to Montesa.

Lampkin had-still has, in fact-a great relationship with the Italian Beta factory. He had the perfect team setup with factory boss Lapo Bianchi and a long-time mechanic, both of whom dovetailed perfectly with his own closeknit traveling family group of dad Martin, mum Isobel, cousin John (Arthur’s son) and more recently cousin James (son of Alan) joining in as his assistant.

But this year, Lampkin thought the Beta thing had gone as far as it was ever going to go (salary-wise, perhaps?) and switched to the Spanish factory owned by Japanese giant Honda.

The first public outing on the factory Montesa Cota 315 came at the opening round of the world indoor championship last winter. It was staged in Sheffield, in Lampkin’s native Yorkshire, and the pressure to win in front of his home fans was incredible. After a nervous start, Lampkin soon appeared to have ridden the Montesa all his life. From then on, his fourth indoor crown was practically a given as he swept to seven wins in 10 starts.

His new team did everything possible to ensure the bike suited its new rider, willingly altering every aspect of the machine, though not without some difficulties. “Moving to Montesa was a big thing,” Lampkin explained. “Once I made the decision to move, I was invited to the factory in Spain to make the bike exactly how I wanted it. There were technicians on hand from HRC, Showa and Montesa to make chassis alterations. It was crazy, and the pressure was intense as we were working on the whole machine in one hit. Every time I tested, they wanted to know about the engine, exhaust, suspension, steering. In the end, I had to say, ‘Right, I’m happy, more or less. I just have to ride it now!’

To win in Sheffield was a huge relief.”

When the outdoor world championships kicked off in Spain earlier this year, Lampkin had the benefit of three months of slightly less intensive testing and training, and three bikes set up exactly how he wanted. Convincing wins in Spain and two more in Portugal crushed his rivals, and in the 14 rounds (two per weekend) held to date, he’s lost only twice. Of these lapses, he is matter-of-fact, “The only reason I lost was because the trials were relatively easy and if you made a mistake you couldn’t get it back. There was nothing wrong with my riding.”

No one looks able to upset the Lampkin monopoly, not even his teammates-1996 world champ Marc Colomer and Fujinami. The question, then, isn’t “Who won the trial?” Rather, it’s “By how many marks did Dougie win?” -John Dickinson

Latitude adjustment

In May, 1999, at High Point Raceway in Mount Morris, Pennsylvania, French motocrosser Mickael Pichón burned his last bridge in the U.S. After a five-year AMA career that yielded two 125cc East Region Supercross titles and a 250cc National win, the now-infamous off-track altercation between his father and track officials led to Pichon’s termination from Team Honda.

Pichón was considered one of the most talented and graceful riders competing stateside, but his results had turned lackluster and his attitude was less than positive. Which meant there was no hope for a ride after Honda gave him the axe. Admittedly tired of the American motocross lifestyle, Pichon headed home to France, where he signed with Sylvain Geboers to race a factory-backed Suzuki in the 250cc World Championship.

Geboers was struggling with young, inexperienced riders, and in desperate need of good results. On the advice of Roger DeCoster, Geboers called Pichon, who used the last few GPs of the ’99 season to get accustomed to the RM250 and begin preparing for the off-season development program.

Eight rounds in, Pichón clearly has found himself. After riding to a dazzling double-moto sweep at round two of the series at Agueda, Portugal, he forged ahead to win in the deep, cocoabrown sand of Valkenswaard, Holland, and on the high-speed Loket circuit in the Czech Republic. In so doing, Pichon stunned his critics-both in America and Europe-and positioned himself to make a run at the title.

So getting fired actually breathed new life into Pichon’s flagging career. “Eve forgotten about what happened with American Honda,” he said, now a bit embarrassed by the notorious incident. “it would have been much better if things ended better because none of it was good. But then I think about what would have happened if Ed stayed with Honda. If I hadn’t left when I did, I wouldn’t be leading the championship. After I left Honda last summer and came to Europe, I signed with Suzuki right away. By doing that, I was able to race the last few GPs and get the bike set up for the 2000 season. If I hadn’t left American Honda, I wouldn’t have been ready for this season.”

When he raced in America, Pichón was a consistent front-runner, which gave him confidence. Now, he’s put that confidence to use on the world stage. “I didn’t win a 250cc championship in the U.S., but I was always close to the front and I always knew I had the speed,” Pichón explained. “In ’98, when I was working with DeCoster, I placed fourth in the 250cc outdoor series and actually ran third for most of the season. I always knew I had the speed, and that I could take that and do well in Europe.”

At the series halfway point, Pichón and defending 250cc World Champion Frederic Bolley-ironically, backed by Honda-went head-to-head on the Brou circuit in France. Before 27,000 wildly enthusiastic fans, the two riders-who between them have won every GP this year, with the exception of the opening round in Talevera, Spain-traded moto wins, continuing their championship battle.

It is Pichón, however, who has been able to turn his methodical, smooth approach into a solid points lead. “Everything is good for me,” he said. “Sylvain is a very good manager. We also only have two riders on the team. (Pichón’s teammate is New Zealander Josh Coppins). In the U.S., we had three or four riders on a team, and that is just too much. By having two riders, the team can give 100 percent to each rider. With three or four riders, there would be one rider doing very good, and the team would push that rider 100 percent and forget about the other guys. I also have a great mechanic, and we have at least one Japanese engineer at every race. Everybody is working very hard, and it is all paying off. I really want to win this title.” -Eric Johnson

McCoy fights the power; Roberts leads

Old-timers, fondly remembering a generation of roadracing Americans who revolutionized Grand Prix riding and dominated the 500cc class, welcomed Garry McCoy’s early season race win in South Africa as if it were the Second Coming. The Red Bull Yamaha rider won the event in flamboyant style, sweeping through the corners in the later laps with his wheels so far out of line he might as well have been spraying dirt on a halfmile oval. Or a quarter-mile Englishstyle speedway track, which is where the 28-year-old learned his craft.

McCoy continued to thrill crowds during the subsequent six roundssideways under braking into the corners, sideways under power out of them. But thoughts of the Second Coming proved premature; he has revisited the rostrum again only once, at the second round in Malaysia, and scored points twice more, in Japan (eighth) and France (fourth).

McCoy is not exactly a class rookie, but he is a beginner on a 185-horsepower four-cylinder two-stroke, having been drafted in halfway through last season to replace off-form Simon Crafar. Until then, he’d raced 125s and a relatively gutless Honda 500cc V-Twin. Meanwhile, this year has offered unaccustomed variety-five different winners in seven races, and only series points leader Kenny Roberts has more than one victory. Close racing, then? Both qualifying times and race results have set new records for closeness, as riders vie to fill the vacuum left by the retirement of Mick Doohan.

The superiority (or otherwise) of McCoy’s technique has not been resolved, largely because of technical complications. Back in the generation led by Roberts’ father, and followed by fellow American champions Freddie Spencer, Eddie Lawson, Wayne Rainey and Kevin Schwantz, spinnin’ and slidin’ the rear was the only way to ride a 500, so hugely had engine performance outstripped traction. European riders who had learned to race on smaller bikes, and relied on high corner speeds and extreme lean angles, were left behind, since their technique no longer worked when the tires went off.

Since then, tire and suspension technologies have improved vastly, and sliding has gone somewhat out of fashion. But McCoy is a special case: Tiny and featherlight, he simply cannot generate rear-wheel traction on par with heavier riders. For him, then, wheelspin is inevitable, not optional. And when Michelin began playing with 16.5-inch rear tires last year, the extra rubber compared with the 17incher suited him just fine. The heavier 16.5-inch tire was slower to warm up, but could put up with the punishment of his wheel-spinning style, so much so that he gained speed instead of slowing down at the end of races.

Michelin was at first reluctant to offer this tire, since McCoy was pretty much alone in preferring it. Even when Yamaha-mounted Norick Abe used one to win the third round in Japan, a classically close race, second-race winner Roberts was one of many who insisted that the 17-incher was a better all-rounder. But by round six, even Roberts was using the new rears, and Michelin by then was developing a 16.5-inch front, as well.

It’s been a year of rain so far-at almost every round. Roberts’ victories have all involved wet weather, one way or another. He won round four at Jerez and round seven in Catalunya. Round five in France went to defending champion Alex Criville-Honda’s first victory after a seven-race drought, their longest no-win spell since 1993. Honda won again in Italy, a tooth-andnail race going to Loris Capirossi after fast-learning class rookie Valentino Rossi fell with a couple of laps to go. Then, Yamaha’s Max Biaggi crashed out on the last lap (typical of his disastrous early season).

That was Honda’s 140th 500cc win, at last breaking MV Agusta’s record, but the factory Repsol team has so far experienced an awful year. Criville has crashed three times in seven races, and has been on the rostrum only at Le Mans, where he won. Teammates Tadayuki Okada and Sete Gibernau have fared even worse, blaming mystery problems with the year-2000 NSR. This theory, however, has been undermined by Rossi, who has been on the pace from the start and is already looking like a future multiple champion.

A character change has seen last year’s prolific crasher Carlos Checa go all sensible, even sharing the points lead with Roberts before the Spaniard crashed out of round seven in Catalunya.

That race was Roberts’ third win, and with the halfway point of the season approaching, he and his Suzuki were emerging as the class act of the post-Doohan era. It’s close all the same, and likely to remain so for the rest of what has been a very good year.

Michael Scott

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontMr. Bonneville

September 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsCafé Americano

September 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCScrewed And Shrunk

September 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

September 2000 -

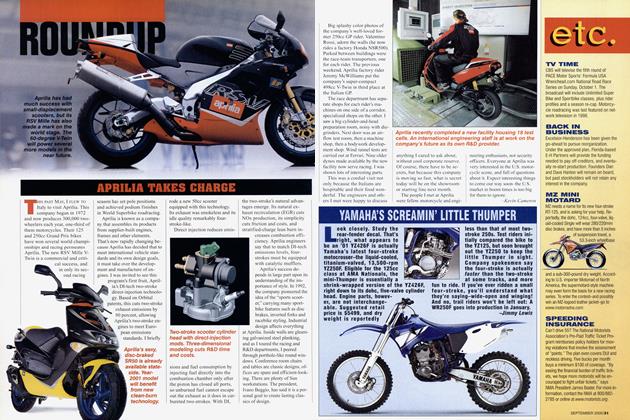

Roundup

RoundupAprilia Takes Charge

September 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

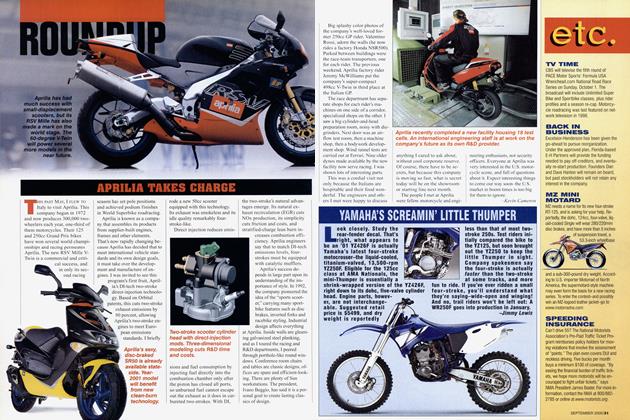

Roundup

RoundupYamaha's Screamin' Little Thumper

September 2000 By Jimmy Lewis