Late-braking news

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

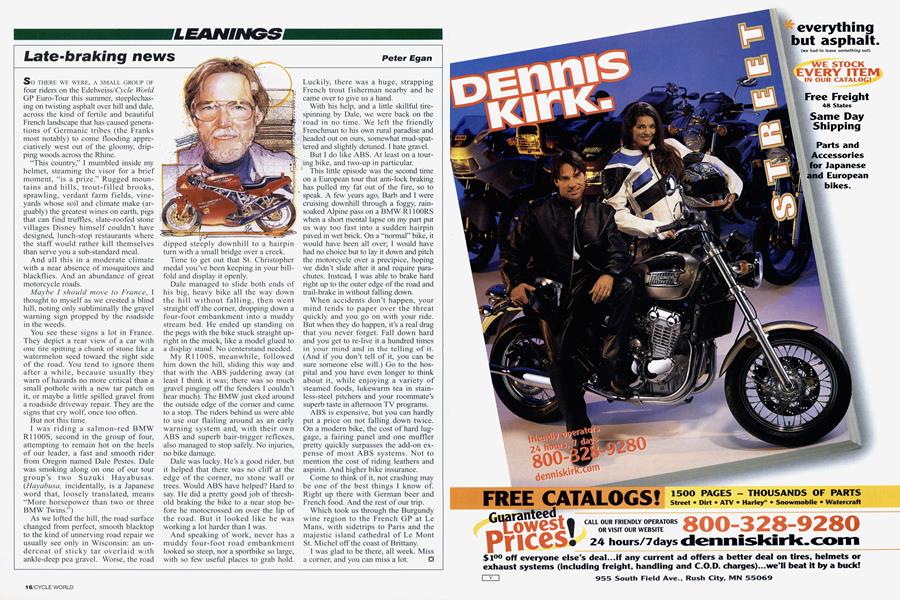

SO THERE WE WERE, A SMALL GROUP OF four riders on the Edelweiss/Cycle World GP Euro-Tour this summer, steeplechasing on twisting asphalt over hill and dale, across the kind of fertile and beautiful French landscape that has caused generations of Germanic tribes (the Franks most notably) to come flooding appreciatively west out of the gloomy, dripping woods across the Rhine.

“This country,” I mumbled inside my helmet, steaming the visor for a brief moment, “is a prize.” Rugged mountains and hills, trout-filled brooks, sprawling, verdant farm fields, vineyards whose soil and climate make (arguably) the greatest wines on earth, pigs that can find truffles, slate-roofed stone villages Disney himself couldn’t have designed, lunch-stop restaurants where the staff would rather kill themselves than serve you a sub-standard meal.

And all this in a moderate climate with a near absence of mosquitoes and blackflies. And an abundance of great motorcycle roads.

Maybe I should move to France, I thought to myself as we crested a blind hill, noting only subliminally the gravel warning sign propped by the roadside in the weeds.

You see these signs a lot in France. They depict a rear view of a car with one tire spitting a chunk of stone like a watermelon seed toward the right side of the road. You tend to ignore them after a while, because usually they warn of hazards no more critical than a small pothole with a new tar patch on it, or maybe a little spilled gravel from a roadside driveway repair. They are the signs that cry wolf, once too often.

But not this time.

I was riding a salmon-red BMW RUOOS, second in the group of four, attempting to remain hot on the heels of our leader, a fast and smooth rider from Oregon named Dale Pestes. Dale was smoking along on one of our tour group’s two Suzuki Hayabusas. (Hayabusa, incidentally, is a Japanese word that, loosely translated, means “More horsepower than two or three BMW Twins.”)

As we lofted the hill, the road surface changed from perfect, smooth blacktop to the kind of unnerving road repair we usually see only in Wisconsin: an undercoat of sticky tar overlaid with ankle-deep pea gravel. Worse, the road dipped steeply downhill to a hairpin turn with a small bridge over a creek.

Time to get out that St. Christopher medal you’ve been keeping in your billfold and display it openly.

Dale managed to slide both ends of his big, heavy bike all the way down the hill without falling, then went straight off the corner, dropping down a four-foot embankment into a muddy stream bed. He ended up standing on the pegs with the bike stuck straight upright in the muck, like a model glued to a display stand. No centerstand needed.

My R1100S, meanwhile, followed him down the hill, sliding this way and that with the ABS juddering away (at least I think it was; there was so much gravel pinging off the fenders I couldn’t hear much). The BMW just eked around the outside edge of the corner and came to a stop. The riders behind us were able to use our flailing around as an early warning system and, with their own ABS and superb hair-trigger reflexes, also managed to stop safely. No injuries, no bike damage.

Dale was lucky. He’s a good rider, but it helped that there was no cliff at the edge of the corner, no stone wall or trees. Would ABS have helped? Hard to say. He did a pretty good job of threshold braking the bike to a near stop before he motocrossed on over the lip of the road. But it looked like he was working a lot harder than I was.

And speaking of work, never has a muddy four-foot road embankment looked so steep, nor a sportbike so large, with so few useful places to grab hold.

Luckily, there was a huge, strapping French trout fisherman nearby and he came over to give us a hand.

With his help, and a little skillful tirespinning by Dale, we were back on the road in no time. We left the friendly Frenchman to his own rural paradise and headed out on ours, somewhat mud-spattered and slightly detuned. I hate gravel.

But I do like ABS. At least on a touring bike, and two-up in particular.

: This little episode was the second time

on a European tour that anti-lock braking has pulled my fat out of the fire, so to speak. A few years ago, Barb and I were cruising downhill through a foggy, rainsoaked Alpine pass on a BMW RI 100RS when a short mental lapse on my part put us way too fast into a sudden hairpin paved in wet brick. On a “normal” bike, it would have been all over; I would have had no choice but to lay it down and pitch the motorcycle over a precipice, hoping we didn’t slide after it and require parachutes. Instead, I was able to brake hard right up to the outer edge of the road and trail-brake in without falling down.

When accidents don’t happen, your mind tends to paper over the threat quickly and you go on with your ride. But when they do happen, it’s a real drag that you never forget. Fall down hard and you get to re-live it a hundred times in your mind and in the telling of it. (And if you don’t tell of it, you can be sure someone else will.) Go to the hospital and you have even longer to think about it, while enjoying a variety of steamed foods, lukewarm tea in stainless-steel pitchers and your roommate’s superb taste in afternoon TV programs.

ABS is expensive, but you can hardly put a price on not falling down twice. On a modern bike, the cost of hard luggage, a fairing panel and one muffler pretty quickly surpasses the add-on expense of most ABS systems. Not to mention the cost of riding leathers and aspirin. And higher bike insurance.

Come to think of it, not crashing may be one of the best things I know of. Right up there with German beer and French food. And the rest of our trip.

Which took us through the Burgundy wine region to the French GP at Le Mans, with sidetrips to Paris and the majestic island cathedral of Le Mont St. Michel off the coast of Brittany.

I was glad to be there, all week. Miss a corner, and you can miss a lot.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontRally At Red Rocks

October 2000 By David Edwards -

TDC

TDCMaking It Happen

October 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

October 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupSpied! Suzuki's Big-Bore Blaster

October 2000 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupGood-Bye, King of the Roads

October 2000 By Brian Catterson -

Roundup

RoundupEtc.

October 2000