LIMPING HOME

On Not Becoming Another Roadside Attraction

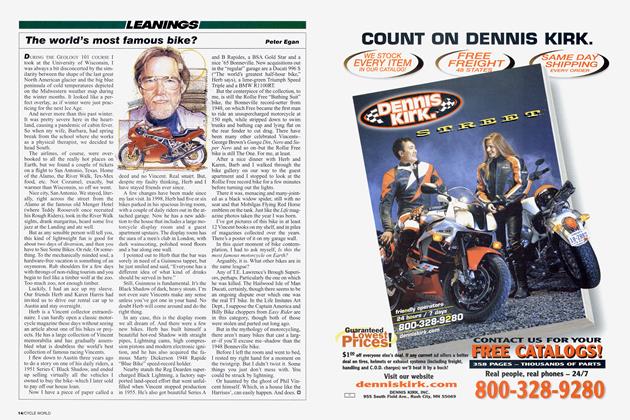

Peter Egan

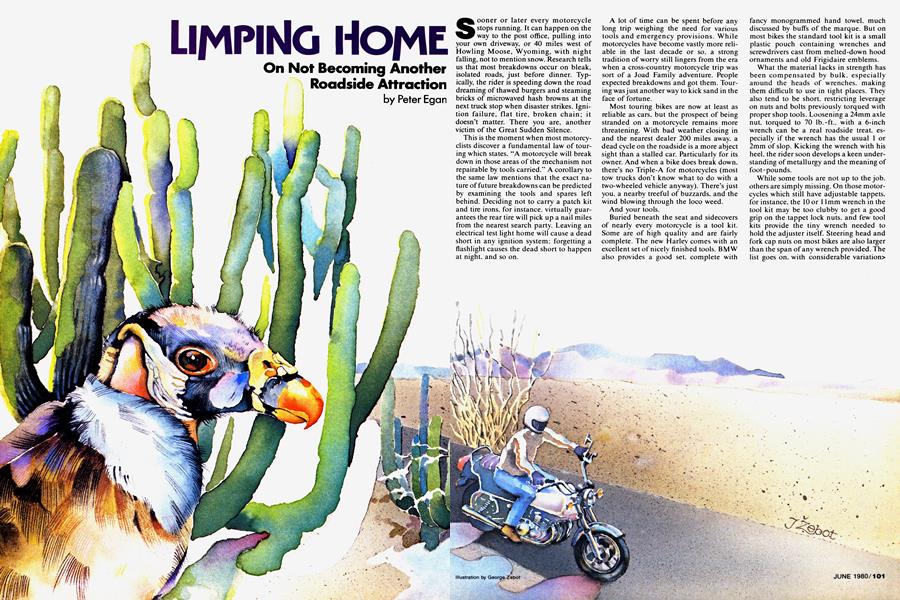

Sooner or later every motorcycle stops running. It can happen on the way to the post office, pulling into your own driveway, or 40 miles west of Howling Moose, Wyoming, with night falling, not to mention snow. Research tells us that most breakdowns occur on bleak, isolated roads, just before dinner. Typically, the rider is speeding down the road dreaming of thawed burgers and steaming bricks of microwaved hash browns at the next truck stop when disaster strikes. Ignition failure, flat tire, broken chain; it doesn’t matter. There you are, another victim of the Great Sudden Silence.

This is the moment when most motorcyclists discover a fundamental law of touring which states, “A motorcycle will break down in those areas of the mechanism not repairable by tools carried.” A corollary to the same law mentions that the exact nature of future breakdowns can be predicted by examining the tools and spares left behind. Deciding not to carry a patch kit and tire irons, for instance, virtually guarantees the rear tire will pick up a nail miles from the nearest search party. Leaving an electrical test light home will cause a dead short in any ignition system; forgetting a flashlight causes the dead short to happen at night, and so on.

A lot of time can be spent before any long trip weighing the need for various tools and emergency provisions. While motorcycles have become vastly more reliable in the last decade or so. a strong tradition of worry still lingers from the era when a cross-country motorcycle trip was sort of a Joad Family adventure. People expected breakdowns and got them. Touring was just another way to kick sand in the face of fortune.

Most touring bikes are now at least as reliable as cars, but the prospect of being stranded on a motorcycle remains more threatening. With bad weather closing in and the nearest dealer 200 miles away, a dead cycle on the roadside is a more abject sight than a stalled car. Particularly for its owner. And when a bike does break down, there’s no Triple-A for motorcycles (most tow trucks don’t know what to do with a two-wheeled vehicle anyway). There’s just you. a nearby treeful of buzzards, and the wind blowing through the loco weed.

And your tools.

Buried beneath the seat and sidecovers of nearly every motorcycle is a tool kit. Some are of high quality and are fairly complete. The new Harley comes with an excellent set of nicely finished tools. BMW also provides a good set. complete with fancy monogrammed hand towel, much discussed by buffs of the marque. But on most bikes the standard tool kit is a small plastic pouch containing wrenches and screwdrivers cast from melted-down hood ornaments and old Frigidaire emblems.

What the material lacks in strength has been compensated by bulk, especially around the heads of wrenches, making them difficult to use in tight places. They also tend to be short, restricting leverage on nuts and bolts previously torqued with proper shop tools. Loosening a 24mm axle nut, torqued to 70 lb.-ft., with a 6-inch wrench can be a real roadside treat, especially if the wrench has the usual 1 or 2mm of slop. Kicking the wrench with his heel, the rider soon develops a keen understanding of metallurgy and the meaning of foot-pounds.

While some tools are not up to the job. others are simply missing. On those motorcycles which still have adjustable tappets, for instance, the 10 or 11mm wrench in the tool kit may be too clubby to get a good grip on the tappet lock nuts, and few tool kits provide the tiny wrench needed to hold the adjuster itself. Steering head and fork cap nuts on most bikes are also larger than the span of any wrench provided. The list goes on. with considerable variation> from one bike to another, but the old ideal of an on-board tool kit that can take a motorcycle down to the crank is nearly gone. What most factory tool kits do best, aside from almost fitting under the seat if you pack them right, is suggest sizes for their own replacement.

In other words, relying on the contents of that little plastic pouch at breakdown time can leave you scanning the horizon for a Snap-On van. A better alternative is to make a few changes and additions ahead of time. The easiest way to build a tool kit for the road is to maintain the bike for a few months using the tools that came with it. Each time you are forced, or merely tempted, to go to the roller cabinet for an improved or missing tool, make a note to take it along when traveling. If the oil can’t be changed using the potmetal open-end supplied by the factory, a replacement is needed.

With the standard wrenches and screwdrivers exchanged or augmented, some other additions can be made. The classic all-purpose tool set usually includes an adjustable wrench, needlenose pliers. Vise-Grips, channel-locks, sidecutters, a hand impact driver (heavy, but nice to have), an electrical test light and a small flashlight.

A small traveling parts department is also a good idea. Touring riders can usually get by with a few light bulbs and fuses, a master and half-link kit (with breaker for endless chains), plugs, points, and a spare clutch cable if it hasn’t been recently replaced.

With that small bundle of tools and parts tucked away somewhere on the motorcycle, most roadside breakdowns are surmountable. In fact, a great many mechanical problems can be overcome with very few tools and spares, or none at all. It may not be possible to return the bike to perfect condition and continue down the road as if nothing had happened, but at least there are ways of holding bad luck at arm’s length and delaying the inevitable.

What follows, then, is a look at some common malfunctions and what can be done, with minimal time and material, to foil encroaching night and limp on back to some warm and brightly lighted place where thorough, careful work can be done. Or on to the next AmTrak station, where the bike can be crated for shipment home.

CABLES

Most common of these to bite the dust is the clutch cable. It is used often, pulls a heavy load, and is continuously flexed, especially at the hand lever. Riding with a broken clutch cable isn’t much fun in heavy city traffic, but it can be done. And on the highway it’s not a serious problem at all. Some solutions:

Carry a spare. If possible, have it prerouted parallel to the existing cable so the tank doesn’t have to be removed at some inconvenient time. A fine idea and often recommended, but hardly anyone bothers except desert riders and people traveling through Gary, Indiana, or New Jersey.

A second alternative is the starter-button-and-kill-switch method. Most electric starters have plenty of power to get a bike rolling in low gear and start it simultaneously. So when the clutch cable breaks you shift clutchless until confronted with a stop sign or traffic light. The bike is then shifted down into first as it rolls to a stop and the kill switch shuts the engine down. When the light turns green, the starter button is punched and the starter rolls the bike forward until the engine lights up. You lurch off and shift clutchless until the next stop, then repeat.

The neutral-light technique is another answer to the same problem. For bikes without electric start, or with weak batteries, it’s best to keep the engine running at stops. Neutral can be found while still rolling. When it's time to go, push off with one foot to get the bike moving fast enough so it won’t kill when you clunk the shifter heavily into first gear, and keep going.

A fourth solution is to carry a CableSpare. This is a small T-handled tool that grips the broken end of a cable at the handlebar and allows you to pull the cable and release it.

Throttle cables are also known to snap, and once broken and frayed do not lend themselves to easy fixing or smooth operation. Most work on the push-pull system, and their failure to do either makes the twist grip useless. No reason to wait for the state patrol to come to the rescue, thereby risking needless registration checks and lectures on cable safety.

Most cycles have an idle screw (or a pair of them) that will push the engine to 4.000 rpm or more. This can be adjusted to put the revs into the lower end of the power band, allowing you to ride at fixed rpm. fishing vessel style, shifting gears for more or less speed.

If a high idle adjustment is not possible with a carb screw, the broken cable itself can be tied off at a frame rail or other appendage, to hold the engine at operating rpm. On multi-cylinder bikes with open carb linkage, a screwdriver, bolt, or even a stick can be wedged under the cable arm for the same purpose.

The only shortcoming of both these methods is that traffic lights or other delays will cause the engine to overheat quickly.

The engine should be shut down whenever more than a very short wait is called for. Clutch lever and kill switch should also be kept at the ready in traffic because backing off the disconnected throttle in an emergency, while it shows a certain degree of imagination, can cause a dangerous delay in stopping.

LIGHTS

A burned out tail light makes an excellent target for onrushing trucks and drivers who are busy lighting cigarettes or drinking from beer cans. The reflector is still there, of course, but only as a weak latewarning device. Screeching brakes, a hail of Armco rivets, and the occasional orange ball of flame in the rear view mirrors are all signs you may have a burned out tail light. The obvious fix is to replace the bulb as soon as possible; either carry one or pull into the nearest gas station. But if the nearest station is closed or thirty miles away, there are ways to survive.

One is to tap on the brake pedal rhythmically to create an emergency flasher effect with the brake light. The brake filament usually remains intact even though the running light is out.

A longer term repair, easier on rider and brakes, is to adjust the spring at the brake light switch so the light stays on all the time. These can usually be adjusted with set screw or double lock nuts on a threaded shaft. A quicker, slipshod approach without tools is to shorten the spring by bending it over the hook on the switch. Either way. you avoid being pushed into the next town against your will.

A failed brake light is less an immediate safety problem, unless you have to stop quickly with someone breathing over your shoulder. In that case flashing the running lights on and off several times will alert the other driver that something new and different is about to happen and put him on guard.

Headlights are a little more serious. We’ve all traveled by sudden moonlight once or twice; and some of us on Bridgestone 50s have even been repeatedly bitten by big black invisible farm dogs who could run faster than 35 mph almost indefinitely. Which proves that sight makes a better guide than touch (or its big brother, pain) on a dark winding road. Generally, high and low beam will not both burn out at once, but if you’ve been riding around with one filament gone, it's only a matter of time.

Headlights of the bulb-and-reflector variety are easy to fix because the bulbs are small and can be carried as spares. A sealed beam headlamp, however, is the standing floor bass in the orchestra of spare light bulbs; not fun to haul around. And when it goes, something has to be done.

The best temporary solution is the buddy method. Riding with another motorcycle, you can tuck in to one side and slightly behind, with both bikes using one light. For lone motorcyclists, a car or truck can sometimes be pressed into service, though not many strangers will gladly consent to guiding a lightless cycle down the road. In a tight spot, you may have to latch onto an unwilling victim until a gas station or parts counter turns up.

One staff member of this magazine actually had his headlight shot out by some fun-loving people at a roadside party in an unspecified part of the continent. Not even stopping to see who had done the shooting, he courageously pulled a flashlight from his pocket and continued the trip at unabated speed.

Gunfire aside, if both beams go out together the problem is more likely a bad fuse or a short in the wiring harness than a bad bulb. Most bikes have a spare fuse clipped somewhere under the fuse block cover. If this is missing, a piece of wire or even a split pin from the front or rear axle nuts can be used to bridge the clips on the fuse block. However, if the fuse blew from a short in the wiring, rather than from age or fatigue, the wiring harness can smolder and burn with a steel pin replacing the fuse. A safer alternative is to make a fuse with self-destructive properties by using a rolled-up piece of aluminum foil, shiny side out. from a chewing gum wrapper or the inside of a cigarette pack.

If the headlight itself is at fault, help can usually be found at the next gas station. The standard 7-inch automotive sealed beam will fit right into most 7-inch motorcycle headlight assemblies, whether they are of the H4 halogen type or the bulband-reflector variety. (Harley Sportsters use a 5'/2-inch automotive lamp). If there is trouble matching the bracketrv. duct tape, that modern answer to chewing gum and baling wire, will hold almost anything together until something better can be found.

TIRES

There is no easy way to change a motorcycle tire. Even pro race team mechanics curse and sweat as they struggle to break beads, pull tubes, stuff valve stems into their holes, and get beads to reseat. In the comfort of a well-equipped garage, just removing a wheel from some bikes can take nearly as long as changing the tire. Out on the highway tire changing problems are compounded by adverse roadside conditions, like muddy gravel or youth gangs in large American cars of the early Sixties.

Three things are needed for a successful tire repair; a decent set of tire irons, a patch kit or spare tube, and some device for pumping air back into the tube. The standard tire irons (or spoons) in most tool kits are short, stamped-steel items w ith burred handles and carefully sharpened edges. These little beauties, apparently supplied bv tube manufacturers, work only slightly better than pitchforks and marlinspikes. In a pinch, screwdrivers or even w rench handles can be used, but only at great peril to the soft, easily-ripped tube. A far better answer is a good pair of smooth chrome vanadium aftermarket irons. Even at $3 or $4 apiece, they make one of the best investments going, and should never be left behind.

A spare tube makes better backup material than a patch kit because a blowout, unlike a puncture, generally leaves the tube unrepairable. Also, older tubes don’t like to be repositioned in the tire and often develop new leaks around areas that have been pinched or folded. Tubes are quite bulky, however, and if you’ve already sawed off your toothbrush handle and endured the same pair of socks for a week, it really hurts to pack a couple of big heavy tubes. Patch kits work well for most punctures and don't take up much room. For tubeless tires, hook-and-plug kits with a small tube of cement also take up little space.

Tire pumps are available in great variety, but the sliding-tube bicycle pump is probably the lightest, most compact design. I always rob my ten-speed when I go touring. An alternative is the can of compressed air with short hose and screw-on tire chuck. The only disadvantage to canned air is when it’s gone it’s gone: if the valve sticks or the tire doesn't bead on the first or second try. you may be in trouble.

A major problem in roadside tire repairs. other than semis blowing your hat and glasses off. is making the tube fall into place so it doesn't pinch or crease. In the garage, liquid soap solution or talc are used to lubricate the tube. rim. and inner tire, so evervthing gets equally distributed inside the tire carcass. Not many touring riders pack liquid soap with them, however. and only a handful of French dukes and wig merchants still carry talcum powder in any quantity. Luckily, plain water works fairly well as a temporary lubricant and can often be found in roadside ditches and other malarial bogs, and transported in some handy container from the roadside litter.

With the tire back in place, the tube should be inflated to a low pressure, then deflated, to insure correct positioning inside the tire. The tire can then be pumped up to maximum possible pressure in a possibly vain effort to make the bead seat. It is often impossible w ith a hand pump to generate the 60-100 psi it takes to seat some tires, particularly on the new wave cast alloy wheels. This is no immediate problem, as the tire can be ridden on without the full bead in position until a gas station or other high-pressure air source can be found. In fact, riding on the tire may cause the bead to pop into place.

If you get a flat and have no tools or repair materials, there is little choice but to remove the wheel and hitch-hike to town. In truly desperate straits riders have filled tires with straw or rags, or soldiered along on the flat tire. This will normally destroy the tire and rim. however, and is an expensive option most often used when survival or prize money are involved.

CHAINS

Chain breakage, like humor, is not pretty. If the rider is lucky, the chain merely arcs off the rear sprocket and falls onto the road. If he’s not. it wraps around a rear shock and locks up the rear wheel, or bunches up at the countershaft sprocket and destroys the engine cases. In other words, the best solution to chain breakage is to prevent it by using a high-quality chain, lubricating it well and replacing it when worn.

But if a chain does break, doesn't destroy the engine, and the owner has no master link, not much can be done except to park the bike behind a shrub and walk to the nearest Yellow Pages. So the trick is to have at least a master link, and preferably a repair kit with a full and half-link, and a small chain breaker on hand. That way one link or more can be removed from the damaged chain and the axle adjusters can compensate for reduced chain length. If a staked link spare rather than a clipped master link is carried, a hammer (or some crude substitute) and a punch will be needed to peen over the end plate.

Master link clips, like transmission detent springs, are notorious for winging off into empty space and being lost forever, so care should be taken during outdoor repairs.

GAS & SPARK

One of the maddening truisms of internal combustion lore is that all stoppages of the mechanically sound engine result from lack of either spark or gas. Makes it all sound simple. There’s no mention of spark and too much gas. spark and bad gas. spark at the wrong time and gas. or subtle combinations of each. The basic premise, however, makes a good starting point in tracking down the immediate cause of a sudden stall. If the engine stops and vou pull off a plug wire that won’t arc to ground (or jolt your socks off), you've got an ignition problem. If the spark works, but the fuel line at the earbs is emptv. there is a gas supply difficulty.

The most common single fuel problem is that of the clogged petcock or fuel filter. Rust, varnish, paint overspray, precipitate of lead, and various other forms of primeval ooze found in the bottoms of gas station storage tanks can collect in the motorcycle gas tank and choke off the fuel flow. Just removing a tank and tilting it abruptly can agitate the bottom layer of sludge and cause it to concentrate at the petcock. Most tanks have a built-in fuel filter, usually a sleeve of fine w ire mesh, but these are delicate and easily ripped or otherwise damaged, and like any filter can become overburdened and clogged.

On the roadside, removing the fuel hose at the carb and blowing back through it will often clear the line until a more thorough cleanup can be made. But it’s always a good idea to check the in-tank filter before a long trip, particularly if the bike has been around a few years, and to install an inline filter as a second defense against a dirty load of gasoline. Even if suspended crud doesn't stop the flow entirely, it can get into the float needles and seats, dumping all vour gas out the overflow tubes and onto the road while you ride along in the mistaken belief your tank is full, as 1 discovered on a trip almost to Watkins Glen. Running out of gas is the ultimate cure for leaky carbs.

Stuck floats and leakv overflow tubes can be handled temporarily by turning the fuel petcock to off. riding until the engine begins to stagger from starvation, then turning the fuel back on just long enough to fill the float bowls and surge another quarter mile or so toward civilization.

The obvious should not be overlooked in checking out anv fuel supply problem. A clogged vent in the filler cap can stop flow, as can a kinked fuel line. One of our new' test bikes recently stalled out on the freeway because the fuel line folded itself into a crease at a sharp bend over the carb linkage. (Time for another law'; “Gasoline will leak prodigiously from apparently sound gaskets, petcocks. welds and threaded junctions, yet is helpless to seep past the smallest obstacle in the path of intended flow. A microscopic piece of grit in a carb drilling or idle jet will stop gasoline; $50 worth of welding on a cracked gas tank will not.)

The new vacuum operated, petcocks. while relatively foolproof, can develop a problem if the vacuum line to the intake manifold or carb becomes disconnected, because there is no draw to release the diaphragm and start the gas flowing. Most of these units have a “prime” position on the petcock. and a tw ist of the screwdriver will resume delivery.

Ignition failures on the highwav offer a lot more room for speculation than. say. broken clutch cables or flat tires. The hard part, as any sociologist knows, is prioritizing the options and targeting the problem areas. Negative growth, voltwise. is a terrible thing.

On road bikes with battery and coil ignition, the battery and contact points (if the bike still uses points) make two excellent places to start looking for trouble. If the bike stops running and all the lights go out at the same time, a battery connection or main fuse are probably to blame. If the decline to full stop is accompanied bv weakening lights, feeble horn, and a starter that won’t turn over, the charging system, battery, or connections are suspect. Snap connectors between components, like the multiple-prong types on voltage regulators and rectifiers, develop a heavy green oxide coating after a few years and can lose continuity altogether. Snapping and unsnapping these a few times will often restore temporarv contact, but thev should be sanded with a piece of emerv cloth or scraped with a small penknife blade when time permits. Same for intermittent battery cable connections. Ground wire failures, due to dirt, looseness, paint, or electrolysis between dissimilar metals are also common on older bikes and should be treated the same way.

A 12-volt test light w ill save a lot of time in tracking down bad connections, and a small volt-ohm meter like those sold in radio supply stores works even better, because continuity can be checked without power to the wire or connection being tested. With a volt-ohm meter and the factory wiring diagram in the owner’s manual, nearly anv break can be found eventuallv. if you don’t go blind reading a wiring diagram photographically reduced from a wall chart into a 3 x 5 card. A real shop manual, rather than the how-to-engage-first-gear owner’s pamphlet, is a good companion on anv trip.

If the spark fails w'hen the battery is up and the charging system is working, ignition trouble of the primary or secondarv kind may have cropped up. If there is a strong spark to ground from the end of the high tension lead, the plug(s) should be looked at for fouling, cracked insulator, tracking and other defects. Plugs will sometimes fire, when properly grounded, out in the open air. vet not w'ork under the rigors of internal combustion. Switching plugs from working to non-working cvlinders on Twins and Multis is a good wav of verifying plug problems. An oil or gasfouled plug can sometimes be made to fire and motivate the machine down the road by pulling the high-tension terminal boots about 3/16-inch away from contact with the spark plug. A snapping sound will be heard as the spark jumps from the terminal to the plug end. The added resistance increases voltage at the plug eore and encourages the spark to jump its gap rather than following gas, oil. or other deposits along the insulator to ground.

continued on page 149

continued from page 106

When there is no jolt at the plug wires, the problem is farther upstream. In any points-and-coil system, the contact points are the weakest link. Pitting, misalignment, and amazingly small amounts of dirt or oil (even fingerprint oil) can disrupt the crucial switching that controls power flow through the coil’s primarv windings. No contact, no spark from the coil.

The first check on points operation should be to see that they are opening and closing. A poorly or non-lubrieated cam can cause the plastic or fiber material on the points block to wear quickly, leaving the points permanently closed. If they appear to be opening and closing properly, rotate the engine until they close, turn on the ignition switch, and push the contacts carefully apart with a small insulated screwdriver. This should cause a blue spark to snap across the opening contacts. If it doesn’t, either no power is flowing from one side to another because of a bad contact surface, or there’s no power coming in from the primary lead off the coil.

Quickly grounding the hot side of the points to the backing plate when the contacts are open will produce a spark if there is current to the points. If not. either the points are grounded, or the problem is in the primary wire, coil, kill or ignition switch, or any of the connections between those components. A test light or volt-ohm meter work best in backtracking through the primary system, but striking small, quick arcs to ground with bare wire ends will work in an emergency.

If there is power to the movable side of the points, but it isn't getting across to the grounded side, the contact surface needs work. If oil or dirt are the problem, a small can of contact cleaner and a piece of smooth paper are nice to have along. Otherwise the points can be cleaned with the corner of any business card donated bv an encyclopedia or cutlery salesman. Badly pitted contacts should either be replaced or dressed with a points file, then regapped. The bike should be retimed as soon as possible after any emergency gap adjustment (immediately, if it backfires or won't start).

Condensers are another source of trouble in anv points setup, and should be checked for loose screws to the backing plate and poor ground at the condenser body. If evervthing is clean and tight and the points are badly burned, the condenser may be shorted to ground internally, in which case it has to be replaced. Filing the oxide and pitted surface off the points faces may allow the contacts to work for a> short time until they burn again, and until new ones can be found. Spare points and condensers are small and, like spare fuses, always worth having along for the ride.

Magneto systems which still use breaker points are subject to all of the same problems. except that lack of battery current to the primary makes it hard to check for continuity problems. Most magneto failings are traced to points malfunction, lowspeed plug fouling, bad connections, or loose coil screws that result in excessive air gap between flywheel magnets and coil. As with battery-and-coil systems, most of these problems can be corrected, at least temporarily, with hand tools by the roadside.

Not so with breakerless electronic ignition. These systems offer a lot of advantages over points-and-coil types; higher amperage through the primary and. hence, more voltage to the plugs, longer build-up time, accurate triggering of the spark, no maintenance, and no high-rpm bounce or other erratic behavior. Their only real disadvantage is that semiconductors embedded in blocks of plastic resin are difficult to repair with pliers and screwdrivers. These systems are repaired by plugging in expensive modules and black boxes until everything works again. And they are easily damaged by electrical malpractice; running current flow backwards, charging batteries in situ, using improper test gear, arc welding on the frame, etc. Things don’t go wrong that often, but when they do. roadside repairs are pointless. The bike has to be pushed, towed, or hauled to the nearest dealership.

So much for motorcycle problems.

The problem with troubleshooting and repair guides is that they always make the modern motorcycle sound like a collage of weak points and the wellspring of all lurking disaster, which is unfair of course. In the thousands of collective miles accumulated on motorcycles of all types and ages by staff members of this magazine (who are also of all types and ages), the disabling breakdown is a genuine rarity. There are people who ride daily and tour continents who never have flat tires; others who have never suffered an electrical failure, even on a succession of British bikes. Fortunately, most problems announce themselves with visible wear or faltering performance long before the machine rolls to a dead stop. But on those rare occasions when careful maintenance and thoughtful preparation are paid off in bad luck, it helps to have a few tricks and a handful of tools and spares up your sleeve, or somewhere.

It’s also reassuring to know that most motorcycle engines stop running because they are out of gas. and most fail to start because the kill switch is turned off.