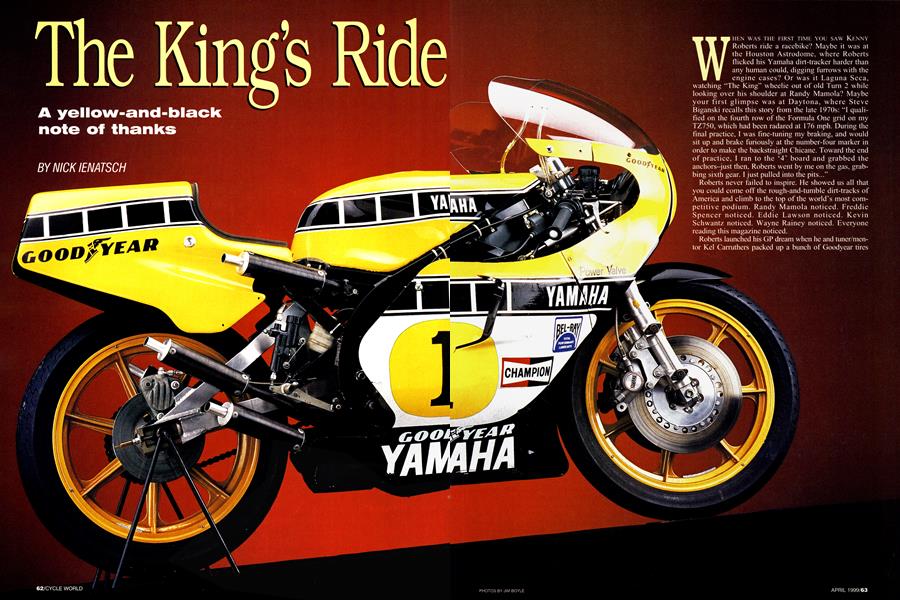

The King's Ride

A yellow-and-black note of thanks

NICK IENATSCH

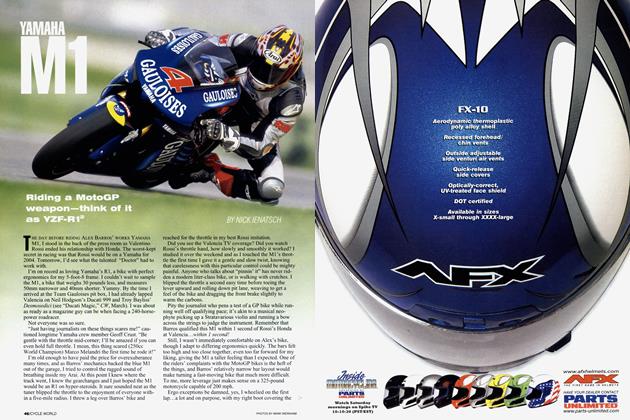

WHEN WAS THE FIRST TIME YOU SAW KENNY Roberts ride a racebike? Maybe it was at the Houston Astrodome, where Roberts flicked his Yamaha dirt-tracker harder than any human could, digging furrows with the engine cases? Or was it Laguna Seca, watching "The King" wheelie out of old Turn 2 while looking over his shoulder at Randy Mamola? Maybe your first glimpse was at Daytona, where Steve Biganski recalls this story from the late 1970s: "I qualified on the fourth row of the Formula One grid on my TZ750, which had been radared at 176 mph. During the final practice, I was fine-tuning my braking, and would sit up and brake furiously at the number-four marker in order to make the backstraight Chicane. Toward the end of practice, I ran to the ‘4’ board and grabbed the anchors—just then, Roberts went by me on the gas, grabbing sixth gear. I just pulled into the pits...” Roberts never failed to inspire. He showed us all that you could come off the rough-and-tumble dirt-tracks of America and climb to the top of the world’s most competitive podium. Randy Mamola noticed. Freddie Spencer noticed. Eddie Lawson noticed. Kevin Schwantz noticed. Wayne Rainey noticed. Everyone reading this magazine noticed. Roberts launched his GP dream when he and tuner/mentor Kel Carruthers packed up a bunch of Goodyear tires and trundled off to Europe in 1977. Few of us can imagine the challenges he faced-not just from dangerous racetracks that leapt over railroad tracks and skirted unprotected Armco barriers, but from the overwhelming difficulty of simply finding the racetrack in, say, Yugoslavia. It was a crazy time. It required superhuman effort. Without heaping undue praise upon Roberts, it’s fair to say he developed and refined modem Grand Prix racing. While his competition often smoked cigarettes and partied ’til dawn, Roberts experimented with a rigid training regimen that included a carbohydrateand protein-rich diet. During the late ’70s, every few months brought a rush of new technology: wider wheels, more aggressive frames, more horsepower, lighter parts. And much of that rush was propelled by the man from Modesto. From what we ride, how we ride and how we train, to racetrack safety, sanctioning-body organization and even what we eat on raceday, Roberts drew us a blueprint good enough to beat the world. And he’s still on the throttle today, developing the 500cc Modenas Triple.

For many years, I felt I could never thank this man who I respected so much, first as a fan, then as a journalist and, finally, as a racer. That all changed in 1996, when my tuner Steve Biganski and I visited KR’s ranch for a magazine story. After a few hours of riding and photo shooting, Kenny volunteered that he had “an old racebike in the barn.” Buried in the back of one of the garages, under a few dusty blankets, was a yellow-and-black Yamaha that spun my mind back to Faguna Seca, where I had snuck into the pits after riding from Salt Fake City to see my first motorcycle race. I was stunned. Kenny’s “old racebike” was his 1980 world-championship-winning TZ500, the factory OW48. He dragged the bike out into the sun and we spent another hour poring over the neglected warrior. As we were leaving, Steve and I offered to take Kenny’s bike home and revitalize it. Surprisingly enough, considering Roberts’ well-known irritation with journalists, he said yes. Biganski and I giggled all the way home, stopping at our friends’ houses to show them what we had. Scott Guthrie, a man with more than 50 Bonneville speed records to his name, most of them on TZ-powered bikes, joined me for the initial disassembly. Guthrie's expert advice put us on jE4Il a two-year path of restoring some alarm ing problems, many of them caused by Yamaha itself. Why? Because this bike, given to Roberts as a mantelpiece, was not meant to run again. Parts were missing, broken or oth erwise mangled. Throttle cables were cut, carb needles missing, wiring gone, engine frozen by the sludge that forms when water and mag nesium mix for 16 years. The monoshock was fluidless, and every piece of rubber was rock-like, including the Goodyear slicks. The magnesium top triple-clamp was bro ken. Guthrie knew that com plete disassembly was the only answer. The bike came apart. Out of the woodwork came help. Everyone I asked to assist in the restoration said, "Sure, what can I do?" There was never a question about the money they were spending or the time required. They did it for Kenny. Biganski was indispensable, sourcing the missing carburetor needles, then rebuilding the Mikunis and making a set of throttle cables. He would do much more. Jim Granger of Granger's Classic Autobody in Reseda, California, matched the wheels' stock gold paint and made them look new again, then tackled the technically difficult job of welding the magnesium triple-clamp.

Dynojet's Michael Belcher took on the brake system, soaking the frozen calipers for weeks before finally being able to press the pistons out of the bod ies. He sourced the parts needed for the rebuild and returned the pieces ready for war, while Mesa Hose built a set of stainless brake lines. Meanwhile, Guthrie researched the engine prob lems, finally shipping the engine to Roberts' race shop in England for a complete rebuild. Goodyear race slicks being unobtain able, Dunlop's Jim Allen kindly rum maged a pair of 18-inch intermediate rain tires from some corner of a ware house. These fit the rims fine, but didn't provide the most confidence-inspiring of profiles, so the search will continue for more suitable rubber. Meanwhile, Tom Hicks at RaceTech rebuilt the shock while marveling at its light weight and trickness, a theme that carried through to the rest of the bike. Despite the OW's

age, carbon-fiber and titanium were sprinkled about, leading Biganski to mutter many times, "I didn't even know these pieces were available back then." To the regular guys, they weren't. With the OW's parts spread out to the far corners of the Earth, my pal Andre Castaños and I did the little stuff like prep the pieces for reassem bly, administer first-aid to the racerrough bodywork and lever tires off and on the rims. This would be no full-on restoration, though; we'd return the OW to the condition it was in when Kenny last rode it, warts and all. After all, this is a battle-scarred, Grand Prix winning motorcycle saved from a time when the Japanese had little sense of history and simply crushed all bikes at the end of the racing season, then start ed over. This wouldn't become an over-restored museum piece. Guys like Carruthers, Trevor Tillbury and Nobby Clark had last wrenched on this bike, so it was an honor just being near it. That feeling was shared by everyone who touched a part. As the pieces trickled in, reconstruction began. Castaños and I did what we could, but Biganski `s inherent knowledge gained from racing these things since 1974 was an amazing aid. He synchs four carburetors better by ear and eye than most of us can with mercury gauges.

The AMA asked me to return the bike to Roberts during the 1998 awards banquet in Las Vegas, and we finally fired the bike one week before the ceremony. But it wasn’t easy. After the studio photos here at CW, I took the bike to Ron Wood’s nearby shop to get it running. Imagine my grief when I poured water into the radiator only to watch it dribble out of the number-four cylinder base gasket! I needed help, and Biganski was out of town on vacation. A quick call to Performance Machine got Todd Silicato on the phone, and minutes later (with PM owner Perry Sands’ blessing), he was on his way to help. Silicato was fresh from winning the AMA 250 Championship with rider Roland Sands, so I figured he knew a thing or two. I figured right. Todd discovered massive galling around the outside rear head stud, which was allowing water to seep past. He dressed the area and built a seal before reinstalling the jug and refastening the head. Two-strokes are blessedly easy to work on. We let the fix set-up overnight, and the next day Biganski returned to synch the carbs and set the ignition timing. The bike fired instantly and the sound took us both back to Laguna Seca, Daytona, Road America, Loudon... After two years of work, we laughed together through the blue haze, a happiness shared between friends who have done a great deal together. The bike was done. Roberts would receive it at the AMA dinner, then ride it the next morning for the first time in 18 years.

After AMA President Ed Youngblood presented Roberts with a Lifetime Achievement Award, I was invited onstage to present the bike. As we walked down off the stage, somebody from the back yelled, “Start it up!” Figuring the Flamingo Hilton wouldn’t be too crazy about that, we kept walking. More calls from the crowd to start the OW, but Kenny and I headed back to our table. Just then, Honda’s Al Ludington taunted, “You guys haven’t got the balls to start that thing.” Kenny stopped, looked at me and asked, “Will it run?” Without a second thought I answered, “Absolutely!” Kenny tossed his award to a friend and we walked to the TZ. I rolled it back to the far wall, Kenny reached down and turned on the gas, clicked it into gear and we ran across the carpet in our tuxedos, pushing a 1980 TZ500. KR popped the clutch, the bike sputtered, he popped it again and music rushed out of the four carbon-fiber mufflers, filling the room with horsepower, Castrol haze and screaming applause. Kenny lit that room up with two big handfuls of throttle, then hit the killswitch. The room rocked. Kenny's eyes sparked and he drolly commented, "Starts better now than in `80."

The following morning, Kenny arrived at the Freddie Spencer School to have some fun on his old warhorse. Speedvision was there, as well as some fans and friends-and, of course, the bike wouldn't start! Castanos and I cleaned the plugs while Kenny learned his way around Las Vegas Motor Speedway on one of Freddie's loaner VFRs. (Roberts on a Honda?)

After some fettling, the TZ fired and sounded righteous, and Kenny looked perfect on the diminutive bike. "I'll go out three or four laps," he yelled over the exhaust, but was still on the track after six. I walked to the middle of the infield and stood with a perma-grin on my face, watching a man and a bike

that have impacted my life in three sig nificant ways.

I've already referred to seeing Roberts at Laguna in 1982 during my introduc tion to roadracing, the weekend I was hooked on yellow-and-black Yamahas. Well, a girl named Judy Perez once saw Kenny Roberts at Daytona during an ABC Sports broadcast, and the image of him on his yellow-and-black Yamaha prompted her to buy a motorcycle with the intention of dragging her own knee. She brought her bike to Willow Springs to participate in a roadracing school I was teaching. Since then, she's become Judy Ienatsch. Thanks, Kenny.

And, finally, Roberts' third major impact on my life came in 1991, at a Yamaha-sponsored gathering. I raced a TZ250 in the AMA series that year, fin ishing third overall to Jimmy Filice and Chris D'Aluisio, but was completely burned-out trying to juggle journalism and full-time racing. I was standing out side the meeting room when Roberts walked by. Before I could nervously

introduce myself, Kenny offered, "You're riding that 250 pretty good." I stood there in shock as he walked down the stairs. That simple comment revital ized my racing aspirations, and the next few years were good to me. -

All these things ran through my mind as KR blasted around the track. Fortunately, I didn't have to try and express my feelings in words-the bike did that for me. Earlier that morning, Kenny put his hand on my shoulder and quietly thanked me and all the

guys who helped. It was easy to see he was smitten with the bike. My friends and I rebuilt this motor cycle to express our gratitude for Kenny's contribution to our individu al lives, and to our chosen sport and profession. And I'll bet any one of Cycle World's 325,000 readers would have answered the call to help with this labor of love. In 1980, Kenny Roberts sat atop the world; now he has the bike that put him there. And it runs good.