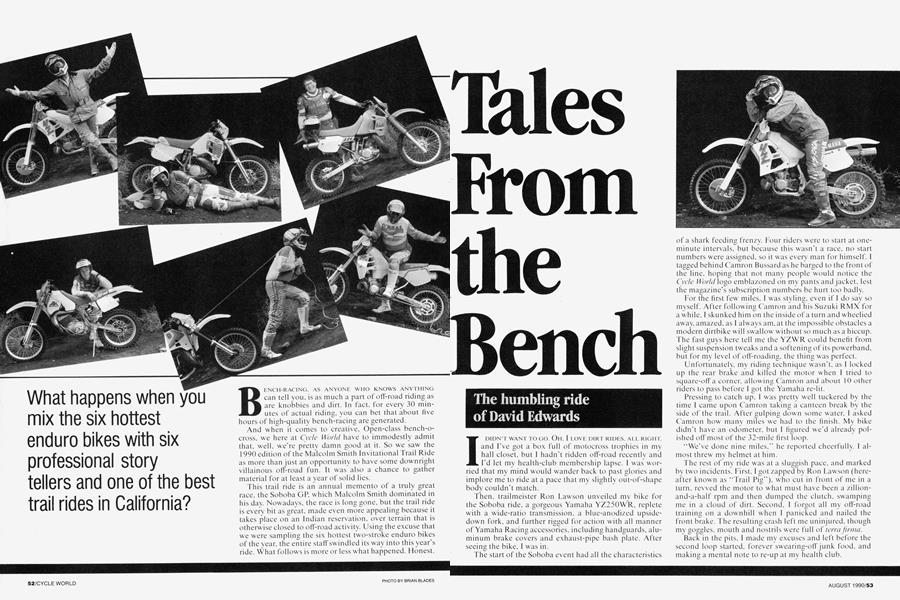

What happens when you mix the six hottest enduro bikes with six professional story tellers and one of the best trail rides in California?

BENCH-RACING, AS ANYONE WHO KNOWS ANYTHING can tell YOU, is as much a part of off-road riding as are knobbies and dirt. In fact, for every 30 minutes of actual riding, you can bet that about five hours of high-quality bench-racing are generated.

And when it comes to creative. Open-class bench-o-cross, we here at Cycle World have to immodestly admit that, well, we’re pretty damn good at it. So we saw the 1990 edition of the Malcolm Smith Invitational Trail Ride as more than just an opportunity to have some downright villainous off-road fun. It was also a chance to gather material for at least a year of solid lies.

This trail ride is an annual memento of a truly great race, the Soboba GP. which Malcolm Smith dominated in his day. Nowadays, the race is long gone, but the trail ride is every bit as great, made even more appealing because it takes place on^an Indian reservation, over terrain that is otherwise closed to off-road activity. Using the excuse that we were sampling the six hottest two-stroke enduro bikes of the year, the entire staff swindled its way into this year’s ride. What follows is more or less what happened. Honest.

Tales From the Bench

The humbling ride of David Edwards

I DIDN'T WANT TO GO. OH, I LOVE DIRT RIDES, ALL RIGHT, and I've got a box full of motocross trophies in my hall closet, but I hadn't ridden off-road recently and I'd let my health-club membership lapse. I was worried that my mind would wander back to past glories and implore me to ride at a pace that my slightly out-of-shape body couldn't match.

Then, trailmeister Ron Lawson unveiled my bike for the Soboba ride, a gorgeous Yamaha YZ250WR. replete with a wide-ratio transmission, a blue-anodized upsidedown fork, and further rigged for action with all manner of Yamaha Racing accessories, including handguards, aluminum brake covers and exhaust-pipe bash plate. After seeing the bike. I was in.

The start of the Soboba event had all the characteristics

of a shark feeding frenzy. Four riders were to start at oneminute intervals, but because this wasn't a race, no start numbers were assigned, so it was every man for himself. I tagged behind Camron Bussard as he barged to the front of the line, hoping that not many people would notice the Cycle World logo emblazoned on my pants and jacket, lest the magazine's subscription numbers be hurt too badly.

For the first few miles, I was styling, even if I do say so myself. After following Camron and his Suzuki RMX for a while. I skunked him on the inside of a turn and wheelied away, amazed, as I always am, at the impossible obstacles a modern dirtbike will swallow without so much as a hiccup. The fast guys here tell me the YZWR could benefit from slight suspension tw eaks and a softening of its powerband, but for my level of off-roading, the thing was perfect.

Unfortunately, my riding technique wasn't, as I locked up the rear brake and killed the motor when I tried to square-off a corner, allowing Camron and about 10 other riders to pass before I got the Yamaha re-lit.

Pressing to catch up, I was pretty well tuckered by the time I came upon Camron taking a canteen break by the side of the trail. After gulping down some water. I asked Camron how many miles we had to the finish. My bike didn't have an odometer, but I figured we'd already polished off most of the 32-mile first loop.

“We've done nine miles,” he reported cheerfully. I almost threw my helmet at him.

The rest of my ride was at a sluggish pace, and marked by two incidents. First, I got zapped by Ron Lawson (hereafter known as “Trail Pig”), who cut in front of me in a turn, revved the motor to what must have been a zillionand-a-half rpm and then dumped the clutch, swamping me in a cloud of dirt. Second, I forgot all my off-road training on a downhill when I panicked and nailed the front brake. The resulting crash left me uninjured, though my goggles, mouth and nostrils were full of terra firma.

Back in the pits, I made my excuses and left before the second loop started, forever swearing-off junk food, and making a mental note to re-up at my health club.

The survival of Jon F. Thompson

YEEEII! EYES WIDE. TEETH GRITTED. FLAT-OUT IN third up a hill so steep you'd need climbing aids to crest it on foot. A hard left at the top onto a ridge as sharp as a knife edge. then straight down a trail so steep I want to reach for a rip cord. Knuckles white. fingertips asleep. I'm hanging on so hard. But I survive. And I keep on surviving throughout the entire ride. I endure the final set of whoops. and motor into the pits. panting. My wife Laura climbs out of the truck, grins, and says. "Cheated death again. eh?"

Indeed. 1 was more than a little reluctant when Lawson and Griewe came up with this deal. The Evil Rons ride so

hard that the ground smokes where they’ve passed, as though it had been struck by lightning. When I try to keep up with them, the ground only smokes where I've crashed into it. So, a little defensive action was called for. And that's why I elbowed aside all other contestants for the Kawasaki KDX200 and slapped my brand on its hide.

Held hard against the western flank of California’s Mt. San Jacinto, the Soboba ride has a well-deserved reputation for tough, narrow trails, sharp turns and steep grades. And the KDX has a reputation for being extremely nimble and easy to ride, especially in difficult terrain. The right horse for the course, in other words. Suitably equipped, I rebriefed Laura on my insurance policies, and took off, Paul Dean right behind me.

Now, I won't deny a need for speed, but I also crave survival. So, while there were those who accused me of riding like I was wearing a dress, I prefer to think that I proceeded at a civilized, gentlemanly pace, fast enough to stay more-or-less out of the way, but slow enough not to die. There were those who claim I was a whole lot slower than my motorcycle. Nonsense. I was just keeping some performance in reserve. And the KDX does provide substantial reserves. The bike, brand new, with no more prep than a short break-in, a quick turn of a few loose spokes and a shot of lube on its chain, ran like a watch for the

entire two-hour first loop, providing the precise steering and supple suspension I value in a dirtbike. and recovering even when I'd gotten it so out of shape I could hear the rustling of the wings of doom. My only complaint? Unless I really screamed it on steep, soft uphills, the motor was easy to bog down.

But. hey. no problem! I endured, and I had a far easier time of it than did my partner Paul Dean. About threequarters of the way through, he disappeared from my wake. Nobody ever has to wait for Paul, so I knew there'd been trouble. I stopped and he finally showed up, puffing and sweaty, with a patented PD story. What had happened was—well, listen, here’s a guy who never quits.

Me neither. Because some things, I just don't start. Having survived the first loop of this ride, I did what seemed prudent: Instead of starting the second loop, I allowed Laura to talk me into a late and comfortable lunch.

Paul Dean’s lift for life

IT WAS DEFINITELY A "HUNGER' CRASH. That's what I call those memorable get-offs where you tumble off the side of a hill that's so high. you think you're going to die of hunger before you stop falling, only to wind up in the bottom ofan abyss that's so deep. you think you'll probably die of thirst before getting out.

That pretty much describes the predicament I got myself into by trying to pass another rider on a narrow part of a steep downhill. I didn’t realize he was more out of control than I was until after he had bunted me into the ravine alongside the hill. And once all the sky-ground-sky chaos was over. I found myself lying on my back, slowly realizing, as I peered through the rear spokes of my Husqvarna 250—which had conveniently come to rest on my chest— that I was surrounded by walls that looked too steep to climb, let alone ride up.

Luckily, my Husky and I survived our plummet without any noticeable damage. But the soft, sandy terrain that had so effectively cushioned my less-than-graceful entrance to this chasm also prevented any chance of my riding out of it. The bike restarted with only two kicks, but it just dug a hole with the rear wheel every time I tried to get it moving in any direction that was even remotely upward. Obviously, getting out of this bottomless pit was not going to involve riding.

What it was going to involve, I soon concluded, was lifting. Lots of lifting. An absurd amount of it, actually, since I'd have to drag a 240-pound dirtbike up a 60to 70foot-high hillside so steep and loose that I was barely able to stand on it. I found I could raise either end of the bike about a foot with each try, but every time I'd lift one end,

the other end would slip back down the hill about six or eight inches. All tolled, then, it took me 350 or 400 separate lifts to get the Husky back onto a ridable surface.

It also took most of my energy, as I learned when I tried to resume riding. The Cagiva-built Husky has a wickedly fast engine, decent suspension and capable flat-out handling, but it can be a rather high-effort ride on slower trails. It’s a “rear-steer” bike, meaning that making good time through tight turns—of which the Soboba ride had plenty—requires that you sit as far forward as possible and slide the rear wheel around using the throttle. But, having just done a month’s worth of power lifting in about an hour, I had no more gymnastics left in me, so I just wobbled wearily through the remainder of the first loop.

Back in the pits, where the rest of the CW crew knew nothing of my escapade, everyone was shocked to learn that I had no intention of even starting the second loop. “Geez, Paul” said Camron, “I’ve never known you to quit in the middle of a ride. You’re not getting too old for this stuff, are you?”

“Well,” I replied, “let’s just say that this is my way of admitting that a couple of hours ago, I indeed was ‘over the hill,’ but that as of the past 45 minutes, I no longer am. Understand?”

“No.”

“Good. Let’s keep it that way.”

The case of the cactus vs. Ron Griewe

DOWNHILLS DON'T GET ANY MORE FUN THAN THIS one. Barely into the second loop, it was maybe a half-mile long, steep and loamy, a single groove that twisted and curved around bushes on the greening hillside.

Too bad there were so many people ahead of me, and that I couldn’t seem to match my rhythm to that of my bike—enduro star Kevin Hines’ modified KTM250 E/XC. I'd have loved to have blitzed down this hill, but given the circumstances, I decided to take it easy. No sense in running over any one; after all, this was just a trail ride.

I heard a couple of bikes closing fast, then saw a blur as one of them darted to my right into a deep rain-groove. The bike bounced wildly about, its rider fighting for control as he screamed, “Sorry!”

Sorry for what? He made a clean pass, even if he was a little out of control.

Then it happened.

Suddenly, something rammed me from behind. I was thrownovertheKTM’s handlebar, rolling head-over-boots toward a large prickly-pear cactus. I came to a stop, on my back, right in the middle of the cactus, wondering what had hit me and how much blood I would lose from what felt like 5000 puncture wounds.

As I extracted my body from the cactus, I saw the culprit, next to a new Suzuki RMX250 that was resting upside-down. “Sorry. I didn't mean to hit you. We were dicing and I just got carried away,” said the rider sheepishly.

It was Charles Halcomb, a good friend who also happens to be a world-class ISDE racer and a development rider at American Suzuki. “Halcomb, you dog, are you trying to hurt me?” I growled, trying to sound mad (and doing a pretty damned good job of it).

“Ogre, I didn't know that was you. I’m really sorry. Are

you hurt?”

This was great, I had been taking it easy on this so-called trail ride and now someone takes me out. “Naw, but you can have a few hundred of these cactus needles if you want.”

Somehow, I knew the day would end something like this. I was having too much fun, despite the crowded trail.

But actually, things hadn’t gone well from the start. The KTM300 E/XC I had ordered didn't arrive in time. I first threw a leg over Hines’ 250 just 30 minutes before the start. I knew the suspension was going to be stiffer than I like, but I figured I could live with that as long as the engine’s power and powerband were close to those of Cycle World’s 1989 KTM 250 enduro test bike—smooth, progressive and controllable.

Wrong. This KTM had a violent powerband and was geared way too tall for a tight, twisty trail ride. The bike steered, turned and handled well, but its all-or-nothing powerband demanded a go-for-it, never-quit-fanning-theclutch riding style.

Such a hyper bike is less than fun in rocky, technical sections such as those that greeted riders toward the end of this ride. But my encounter with the cactus ended my ride before I got to the really tough sections. Ron Lawson and Camron Bussard were still running, though. I knew Ron wouldn’t have any problem riding through the nasty stuff, but Cam hadn’t ridden off-road lately. I wondered how he was doing.

Camron E. Bussard in terminal neutral

I 'M NOT DUMB I WANTED TO RIDE THE SECOND LOOP with Ron Griewe. After all, he had ridden this event before and claimed he knew the area. I figured that really meant he knew some ways around the bottlenecks. But in the confusion at the start, I had to leave with the group ahead of him. Still, I thought he would pass me in a few miles, then we could ride together.

But I never saw Ron, and only later did I learn about his affair with that cactus. Anyway, I was too busy with my own problems. I hadn’t ridden a dirtbike in about six months and was feeling just a little rusty. But the Suzuki RMX250 made me feel like a seasoned ISDE veteran. It had all the mandatory RMX modifications, mostly RM parts such as we outlined in our January, 1990, story on taking the bike to the Six Days. So, it had great power and almost-intuitive steering. I don’t know how many times during the first loop the power and handling enabled me to get up hills and over obstacles that I probably should have crashed on.

As the second loop became increasingly difficult, I began to have doubts about making it to the end, especially whenever 1 thought about the rumored cliff the trail fell off of at the end of the ride. Still, I pressed on ever deeper into the loop, until I came upon a bottleneck with riders scattered all along the trail trying to get through a deep creek crossing littered with mossy boulders and expired motorcycles.

By the time I had pushed, lifted and dragged my way out of the ravine and put some distance between me and the drowning masses, I was beginning to feel worn out. Then I came upon what 1 thought was the dreaded downhill. A narrow, sandy trail slid down the side of a cliff through boulders the size of televisions. Riding the front brake and bouncing between the rocks, I made it to the bottom, then hit the gas, thinking the worst was behind me.

As I splashed through one more creek crossing. I did a wheelie for a photographer, then started powersliding through the corners as the now-loamy trail wound under large oak trees. Suddenly, I came to a stop. The chain had thrown its masterlink, leaving me stranded just a few miles from the finish. By the time I had borrowed a masterlink from another rider, I decided to catch the road and limp back to the pits.

It was then that I found out I had not made it to the hill of death, but had broken down just a few miles from it. The hill I had made it down was just a warm-up for the real test at the end of the ride. At first, I was a bit disappointed that I had cut the ride short. But as I began to think about things just a bit more, I felt better. After all, the ride had been a blast, and I was tired enough as it was. Not having completed the second loop also gives me an incentive to go back next year with the goal of finishing the event. Besides, Ron Lawson was still out there, and I was sure he’d tell me, in painful detail, about anything I’d missed.

Ron Lawson and the trail ride that wouldn’t end

N OTHING FELT RIGHT. FIRST OF ALL. THIS WAS A TRAIL ride, not a race, and that was weird enough. For the last 20 years. it seems like every time I've been on a dirtbike, it's been during a race of some sort. And racers ride with three simple rules in mind: 1) If

someone is in front of you, pass him; 2) if someone is behind you, don’t let him pass you; and 3) if you fail the first two rules, always have an excuse ready.

But on a trail ride, no one wants to hear your excuses, and passing is somewhat tacky. I didn't know quite how to deal with it. My friend and AA enduro rider Robb Mesecher told me to be the stealth rider, to dress all in black, without any identifying numbers, names or stickers, then ride like Rambo with a death wish. And afterwards you could just shrug when people asked, “Who was that idiot?

I gave it some thought and decided to have a nice, easy ride, not to race. And when I started off on the ATK 406 Cross-Country, those were my honest intentions. But the bike felt strange at first. It really is like no other motorcycle made, and it takes some getting used to. It revs higher than any Open bike I’ve ridden, and soon I found that it requires an aggressive riding technique. You have to approach turns with the throttle open and the rear end sliding to make things easy. So, gradually my pace picked up. Then I found that the suspension also works better the faster you go. I picked up the pace some more.

Halfway though the second loop, I was going about as fast as I could. The trail was magnificent, with enough twists, turns, uphills and downhills to satisfy anyone. At one point there was a cliff, where you just kind of free-fell until the ground came up to meet your tires. It was great, in a heart-in-your-throat kind of way.

But then came the guilt. I got to the end of the trail completely exhausted, and only a few riders, including 49year-old Malcolm Smith himself, were there. Then, one by one, all the riders I had just passed in various rude and un-

trail-ride-like ways started rolling in and glaring at me. Malcolm and several others started to leave, and I figured any place else was a better place to be, so I followed them.

Mistake.

Malcolm and his friends weren’t going back to camp. They hadn’t had enough, and were starting on a private loop three. For the next half-hour, they dragged me though some of the tightest sections all over again, including the free fall. Only this time I was tired when I started and riding even faster than before. It was as if the trail ride gods had looked down and said, “You want to race, huh? Try keeping up with these guys.”

When it was all over, I was exhausted, humbled and guilty, all at once. I felt like I’d either gone too fast or too slow; I wasn’t quite sure which. But I was sure I'd had a great time. And I can't wait ’til next year. This trail-riding business is strange stuff. But it sure is fun. S

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

August 1990 -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

August 1990 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

August 1990 By Peter Egan -

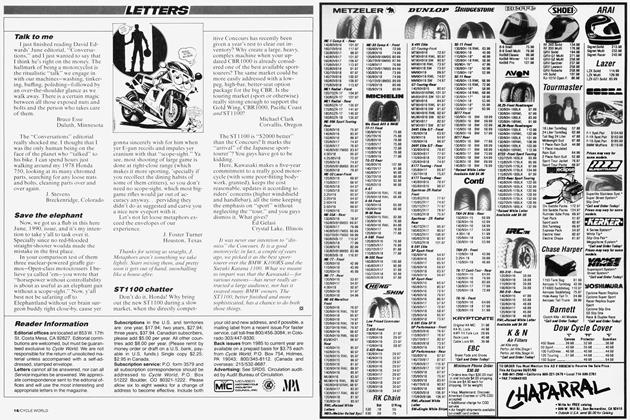

Letters

LettersLetters

August 1990 -

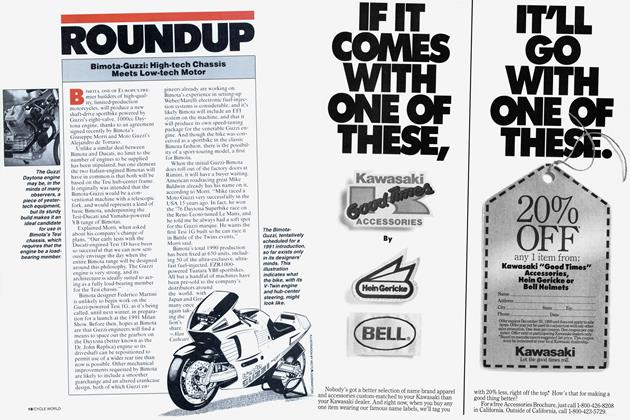

Roundup

RoundupBimota-Guzzi: High-Tech Chassis Meets Low-Tech Motor

August 1990 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupHonda Prices: What Was Up Goes Down

August 1990 By Jon F. Thompson