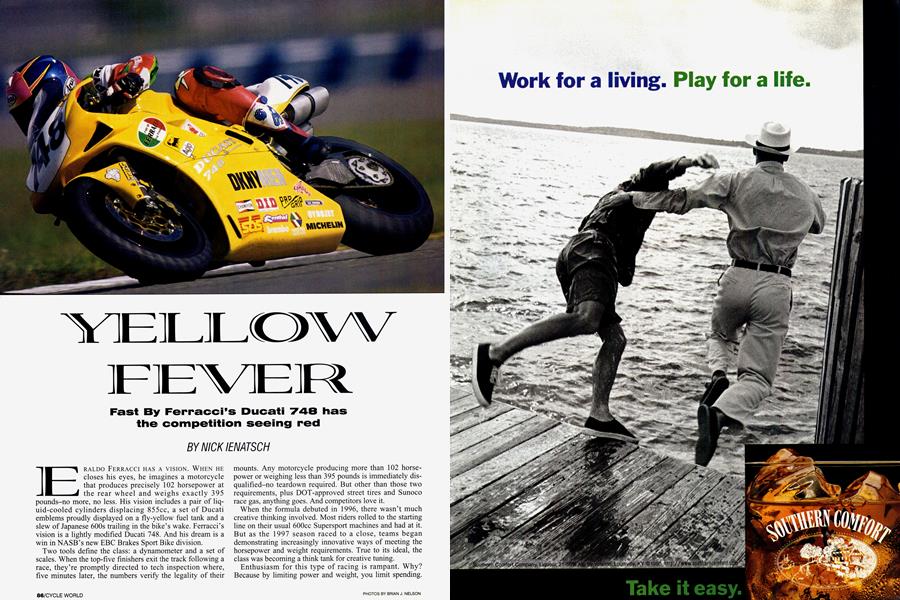

YELLOW FEVER

Fast By Ferracci's Ducati 748 has the competition seeing red

NICK IENATSCH

ERALDO FERRACCI HAS A VISION. WHEN HE closes his eyes, he imagines a motorcycle that produces precisely 102 horsepower at the rear wheel and weighs exactly 395 pounds-no more, no less. His vision includes a pair of liquid-cooled cylinders displacing 855cc, a set of Ducati emblems proudly displayed on a fly-yellow fuel tank and a slew of Japanese 600s trailing in the bike's wake. Ferracci's vision is a lightly modified Ducati 748. And his dream is a win in NASB's new EBC Brakes Sport Bike division.

Two tools define the class: a dynamometer and a set of scales. When the top-five finishers exit the track following a race, they're promptly directed to tech inspection where, five minutes later, the numbers verify the legality of their

mounts. Any motorcycle producing more than 102 horse power or weighing less than 395 pounds is immediately dis qualified-no teardown required. But other than those two requirements, plus DOT-approved street tires and Sunoco race gas, anything goes. And competitors love it.

When the formula debuted in 1996, there wasn't much creative thinking involved. Most riders rolled to the starting line on their usual 600cc Supersport machines and had at it. But as the 1997 season raced to a close, teams began demonstrating increasingly innovative ways of meeting the horsepower and weight requirements. True to its ideal, the class was becoming a think tank for creative tuning.

Enthusiasm for this type of racing is rampant. Why? Because by limiting power and weight, you limit spending. No more costly titanium axles, mag nesium wheels, carbon-fiber bodywork, etc. At the Daytona season finale this past fall, the field consisted mainly of Honda, Kawasaki and Suzuki 600s, plus Ferracci's 748 Duck with yours truly in the saddle.

But Eraldo wasn't the only tuner experimenting with the formula. One of the most potent combinations is a Suzuki GSX-R750 that's been detuned to sneak under the horsepow er limit. So imagine my surprise when, upon exiting Daytona's infield and driving up onto the banking on Ferracci's 748, I watched Richard Alexander motor away from me on what appeared to be a GSX-R600. I later discov ered that the talented rider was aboard a GSX-R750 built by noted tuner David McGrath-a combination that's tough to beat. At Daytona, no one did.

Midway through the `97 season, former Daytona 200 winner David Sadowski installed a GSX-R750 engine in a GSX R600 chassis, hoping to take advantage of the bigger bike's additional midrange punch. At Daytona, both McGrath and Sadowski hinted at 10-15 extra ponies in the midrange. And while both admitted to having restricted the bike's top-end power by fiddling with ignition and car buretion, they were tight-lipped regarding additional details. And who can blame them? After all, NASB pays $1500 for a win, and top finishers can count on significant contingency awards, plus a $100,000 end-of-season points fund that pays $50,000 divided among the top-20 team owners, plus another $50,000 in start money for the following season.

The real thrill, though, is running against quick riders on a variety of restricted bikes. "It's like NASCAR on two wheels," Sadowski enthused at Daytona. Of course, few need to be reminded of NASCAR's popularity. Besides Sadowski, other series regulars include Shawn Higbee on a Buell Si, a Harley-Davidson Sportster-powered V-Twin that's capable of running with the leaders at tighter, more technical tracks. Team Valvoline Suzuki has also gotten in on the act, detuning a Suzuki TL1000S for Grant Lopez, but they got booted for making too much power at Loudon.

As for Ferracci’s vision, it was mighty good right out of the box. The Pennsylvania-based team began with a 1997 748SP, but would have done just fine with a standard 748 because they replaced the SP’s camshafts with standard bump sticks, anyway. While they had the engine apart, they bored the cylinders to accommodate 94mm pistons and reworked the EFI. Can you say “midrange?” All told, the internal engine changes produced 100.8 rear-wheel horsepower at the lowered 10,800-rpm redline, with a whopping 62.9 foot-pounds of torque at 6800 rpm. Ferracci feels that the 748, in this lightly stressed form, will survive a full year of racing with only one rebuild, making for affordable racing. At Daytona, the engine never missed a beat.

Not that we got much practice. Rain ruined two days, and the bike ran out of fuel halfway through qualifying, forcing me to sit and watch the final 15 minutes from trackside. Even so, my earlier laps were good enough for second row on the grid. At the green flag, I launched the Ducati into second place, only to be caught in a drafting war heading into the Chicane.

Sadowski, who sat out the race in order to focus his injured body on wrapping up the Formula USA championship, had warned me to be ready to trade paint in this class, and that the first few laps would be exciting. Up to this point, I had maybe 12 laps on the bike (only eight of which were in the dry), so my learning curve was nearly vertical. I tried to latch onto the lead group, but I wasn’t comfortable with the pace. Every lap was an improvement, though, and by the end of the race I had slipped into the 1 -minute, 58-second bracket, fully 3 seconds per lap quicker than I'd qualified. In the end, Ferracci was rewarded with a respectable seventh-place finish.

Following the race, the bike tipped the scales at 407 pounds, 12 over the limit. Ferracci had fitted Marchesini wheels, but left the exhaust system stock. Future plans call for replacing the mufflers with lighter (but equally restrictive) pieces in an effort to lower the bike’s center of mass and improve traction. The stock footpegs were replaced with FBF catalog items, and the bike wore an FBF electric shifter that made full-throttle upshifts through the close-ratio tranny a joy. HyperPro springs were used in the stock fork, as well as on the Öhlins shock.

Obviously, the horsepower and weight limits did indeed minimize spending, since the bike wore a myriad of stock components, including triple-clamps, clip-ons, fuel tank, under-seat bodywork, brakes and all engine components except pistons and cams. Even the Sharkskinz fiberglass bodywork was off-the-shelf.

So, considering that we came in at the end of the season and grabbed a top-10 finish in a highly competitive class, Ferracci’s vision seems viable. He would like nothing better than to sell turnkey racebikes to competitors, and judging from the interest shown at Daytona, riders are looking for an alternative to the ubiquitous Japanese Fours. The 748’s adjustable steering head and rear ride height, track-ready riding position, wide 17-inch wheels and single-sided swingarm offer advantages that can’t be found in other manufacturers’ lineups. And 63 foot-pounds of torque doesn’t hurt, either. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue