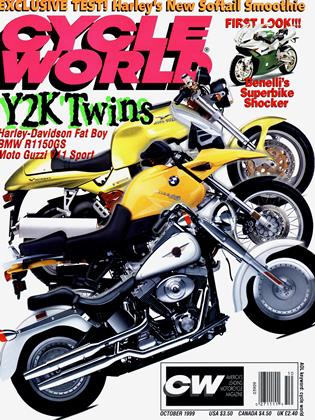

Why Twins, Why Now?

When it to cylinders,less is more

KEVIN CAMERON

How HAVE TWINS returned from oblivion to center stage? Their era seemed to end with the British industry in the early 1970s, giving way to endless elaboration of the four-cylinder engine. Now, everyone has a Twin. Twins are chic, almost reaching the status of art. Twins win races. People want them. Why?

Two central causes: The first is that the four-cylinder performance envelope has expanded beyond the skill (and therefore the interest of the average rider. No one wants to be humiliated by his motorcycle. One by one, older riders have abandoned their interest in this year’s hot 600, 750 or unlimited Four, to seek other pleasures. Recently, that has often meant a Twin. Add to that the power of youth remembered-nostalgia for the BSA or Norton of young adulthood. Add also the proven taste of today’s generation for the music, clothing and pursuits of their parents’ youth. Twins fit.

The second is that Twins have burst through a social barrier that no increase of four-cylinder performance could pierce. Ducati and Harley-Davidson have created irresistible legends into which even previously nonmotorcyclists are pleased to step. By becoming accessories to the lives of corporate CEOs and the fashionable well-to-do, these Twins have done the impossible: found new buyers. Harley’s legend centers on the lone rider, finding a new life of freedom on the open road. Ducati, its success driven ultimately by racing, wears with assurance the exotic Italian style and color of the kind always welcome at the Ritz. This bypasses the commodity approach of the Japanese companies, which seemingly work to blur all distinction between brands, and often ignore the value of legend.

The Japanese, seeing Ducati’s fantastic rise from unreliable curiosity to mostadmired status, finally offered their own Twins-Suzuki’s TLs,

Honda’s VTR and Yamaha’s quarter-hearted 850s. They were dismayed to find that commodity Twins, even if red and gehuinely potent, largely missed the point.

Never mind-that’s marketing. How did Ducati put the sport-Twin where it is today? It was a glorious accident. In 1985, the prototype 851 was just another loud curiosity from the people who had brought us hard-starting, chrome-peeling sporty Singles and elite, heavy-steering, air-cooled Twins. But the FIM was looking appraisingly at American Superbike racing, where Eraldo Ferracci and his rider Dale Quarterley proved the track value of the new 851 design. When the FIM asked Superbike impresario Steve McLaughlin’s advice on a combined Twins/Fours formula, he suggested 1000/750, based on the ratio of engine strokes. This has worked. Four-cylinder 750s make peak power at about 14,800 rpm, the Ducatis at about 10,800-almost exactly the ratio of 1000/750. The rule-makers added a weight break for Twins, and World Superbike racing became a virtually unending success story for Ducati.

Whatever you believe about the fairness of this, it allowed Ducati to eam a reputation that has put it where it is today. Happily for the Bologna company, people were ready for an alternative to Fours, ready for a new paradigm in motorcycling, ready for motorcycles to be chic rather than adolescent. Arty, craftsmanlike Twins clicked with the upwardly mobile. A man of 40 or 50 feels out of place on his son’s 100-bhp 600cc Four, but can be socially comfortable on the (at least equally fast) Ducati 996.

Aside from today’s association with art, style and status, Twins have special qualities simply as motorcycles. First comes the rational shape of a V-Twin-it fits a motorcycle chassis like no other engine, because both are basically two-dimensional. The result is a narrow, compact package. By contrast, the marriage of the inline-Four and the motorcycle puts two principles at right angles to each other.

Next comes sound. A Twin has a deep, animalmusical voice that, to many people, is the essential motorcycle sound. The high shriek of a Four means power only to soulless technicians like myself. It’s programmed into us by nature to perceive a roar as aggression, a scream as fear.

The variety in Twin sounds reveals their many cylinder arrangements. We can think of them all as Vengines with cylinder angles ranging from 0 to 180 degrees. The classic British Twins had a 0-degree Vangle-their cylinders were H parallel. This gives an evenly spaced 360-degree firing interval and the resulting sound is a throaty drone. As the V-angle is increased, firing order becomes more irregular, introducing the interesting syncopation that so many enjoy. For example, 90-degree engines fire at 270 and 450 degrees. Early Twins were built as

Vs because it was an easy way to make a Twin out of a Single, but as revs rose, vibration became a concern. When you give a V-Twin a 60-degree cylinder angle, secondary piston shaking forces become self-canceling-as in Harley’s VR Superbike engine, the new Aprilia RSV Mille or the late John Britten’s V-1000. Increase V-angle to 90 degrees, and primary .piston shaking forces selfcancel-so Ducati, Moto Guzzi, Suzuki and Honda chose this angle for their sport-Twins. The familiar BMW Boxer Twins are “flat”-with a 180-degree cylinder angle, and both cylinders come to TDC together thanks to two separate crankpins at 180 degrees.

A 90-degree V is attractive for balance, but the wide V,‘takes up â lót of fore-aft room on a motorcycle. On some V-Twin cruiser models, Honda has adopted the staggered crankpins pioneered by Moto Guzzi on its prewar 120-degree, 500cc roadracers. While staggered pins can combine natural primary balance with less-than-90degree V-angles on street machines, modem racing rpm has a history of breaking such stagger-pin cranks.

A parallel-Twin is, for balance considerations, the same as a Single because its two pistons move as one. No simple scheme can balance this because straightline, up-and-down motion cannot be balanced by a crank counterweight whirling around in a circle. An unbalanced Single or parallel-Twin jumps up and down along its cylinder axis because of the inertia force generated by the piston’s Tstarting and stopping. Let us call this force 100 percent.

If we add counterweight to the crank, we can reduce this up-and-down force-but only at the cost of creating a new, forward-and-backwards imbalance force at right angles to cylinder and crank axes. If we balance out 50 percent of the up-and-down,

we create the same amount of new, forward-ind-back shaking. If we balance out 100 percent of the up-anddown, we get a forwardand-back shaking equal in force to the old 100 percent up-and-down force. The obvious compromise is to balance only 50 percent of the shaking force. Auto engines are usually balanced this way, because it cuts main-bearing peak loads in half.

When parallel-Twins like those of Triumph, BSA and Norton were balanced at 50 percent, they shook horribly. Up-and-down shaking excited the frame rails into sympathetic vibration and, in any case, humans feel upand-down vibration as more unpleasant than forward and back. Therefore, practical British engineers just

increased the balance

until it felt tolerable, endin; up as high as 75-85 percent It is the resulting large forward-and-back vibration that drives the front wheels of these classic machines into their characteristic whipping motion at idle-sometfiing thát is, in my mind, inseparable from the essence of Triumph motorcycles. -v;

Vibration becomes a sig

nature of an experience.

Vertical-Twins shake, but 90-degree V-engines do not. BMW flat-Twins are smooth, with both primary and secondary shaking forces being self-canceling.

;Yeft because their two cylinders can’t be located in the same plane, there remains a small rocking force, tending tcf twist the engine back and rorth around a vertical axis. This is “BMW buzz,” which never goes away. This is no more an annoyance * BMW owners than front wheel whip is an annoyance to Brit-Twin riders. These are comforting signals that tell them they are at home on their favorite machine. Of course, too much

vibration over long miles is annoying, as any owner of an Evo Softail can tell you. Which is why Harley’s new “Beta” Twin Cam motor is so appealing. The idea of balancer shafts opens many possibilities, for combining two counter-rotating imbalances on separate shafts produces a simple back-andforth shaking force that can be used to cancel piston shaking forces. Milwaukee did not invent the concept, ~bf course. Aprilia’s 60degree RSV Mille engine has such a pair of primary balancers, while Honda’s CBR1100XX engine carries a pair of secondary balance shafts to remove the four’s annoying, high-frequency secondary imbalance. Some people sneer at balance shafts for their extra complexity, but the chassis

veight4hey save results ma net weight saving overall`and they eliminate a major sOurce of rider fktigue. `

Because big engines can maintain high road speed at low rpm, a large-caliber Twin seems to lope along with an attractive lack of effort at highway speeds. Vincent builder Big Sid Biberman likens the cadenced beat of such engines to the comfortable assurance that a cantering horse gives-you hear and feel the pulsating action beneath you, and know there is plenty more where that is coming from. This is, he asserts, more animal than machine.

Turning the throttle on a Twin yields another appreciation. On a four-cylinder bike, with its small flywheel mass, turning the twistgrip is like firing a thruster on a space vehicleyou feel the push, but it „ appears to come from nowhere. When you roll off, it disappears. On a Twin, the flywheel mass is an energy memory, remembering the motion when you roll off, modulating the spin-up when you roll on. Flywheel mass must be large enough that the energy in the spinning crank at idle is enough to push one piston through compression to remain running. The bigger the displacement of one cylinder, the greater the flywheel mass must be, and vice versa.

Riders like the wide torque of a Twin, and Superbike racing has shown that Twins usually have advantages in acceleration off turns. While Japanese Fours have large valve and carb sizes, chosen fo hit impressive horsepower numbers, Twins deliver their peak torque at lower rpm by virtue of proportionately smaller valves and ports/Tiiis i| not so much a matter bf design as of geometry; as you scale up a given cylinder, its valve are becomes smaller in proportion,to its dis-

placement. Ducatis competing in World Superbike

often lack the top speed of the Fours, but more than make up for it in bottom, and midrange acceleration. Ordinary street riders like this characteristic just as much as racers need it-it feels lively and responsive, with less need to row the gearbox to get the performance.

In one sense, Twins are just the novelty of the moment. In another, they are an enduring and natural way to build motorcyclesjust ask Harley-Davidson. Balance or imbalance, smooth or unsmooth, Twins have character, and those who own them come to associate these qualities with the riding experience.