BIKES THAT WOULDN'T DIE

BY JON F. THOMPSON

HAT? ACTUALLY keep something, anyything, beyond its projected design life? Care for it, polish it. maintain it, use it long after it has been superseded by newer, prettier, more sophisticated designs?

Outrageous, you say? A blow to the fabric of modern consumerism, a concept sure to send shivers through the bones of those charged with the sacred responsibility of selling us More Cubic Stuff?

Maybe. But on the other hand, how do you bring yourself to dispose of a trusted friend, one that has]

served you faithfully, just because a measure of something as nebulous as time has passed? Doing that, it seems to us, is precisely like deciding you’re tired of your old dog, that you’ve seen a pup who has keener vision and scent, and sharper reflexes, whose markings and manners you like better. So you shoot the old one to make room for the new one.

Oh, you wouldn’t do that? Neither would we. But when a new motorcycle springs into view, laden of hyper-modern technology and performance, ell, we’re only human.

Instantly, we notice that the twowheeled veteran that currently graces prime position in our garage no longer gleams like it once did. We notice scratches, blemishes, worn places. And our delight in it is diminished. Slowly the seed grows, and sooner or later, the bike is gone, its place usurped by a brand-new bike— which, ultimately, will go the way of the machine it replaced. Sad. but oh, too true.

But not for everyone. Certainly not for the five men and machines profiled here. These are men who’ve stayed the course with motorcycles that have in some cases, over time and miles, become patently obsolete. But while obsolescence was setting in, so was trust. So the bikes have remained in spite of the siren song keened by the lust, which lives in us all, for newer, faster, more perfect motorcycles.

In Casablanca, Bogart and Ingrid Bergman knew it. and so do keepers of old motorcycles: The fundamental things apply, as time goes by.

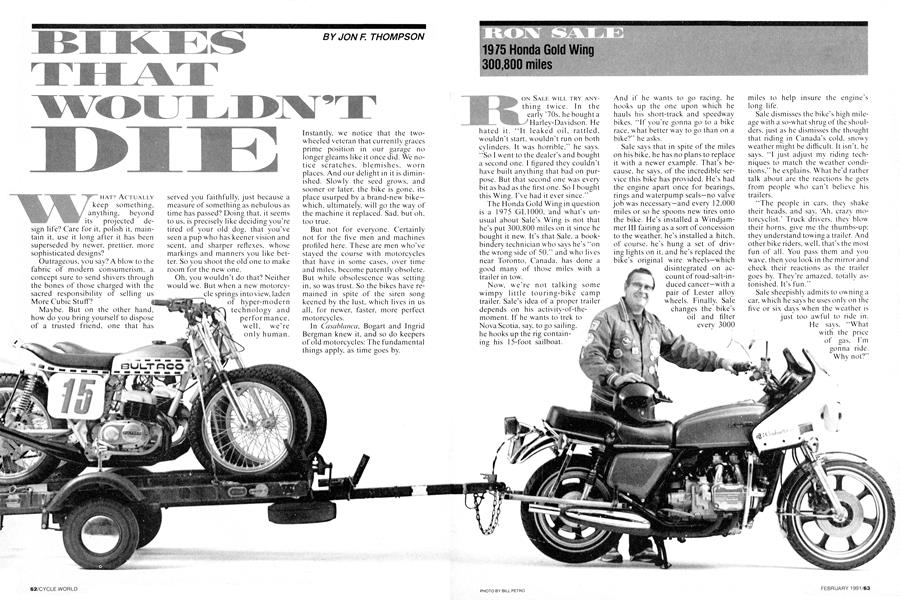

RON SALE

1915. Honda Gold Wing 300,800 miles

ON SALE WILL TRY ANYt h i n 2. twice. In the early '70s. he bought a H a r 1 eyDa v i d so n. He It leaked oil. rattled, wouldn't start, wouldn't run on both cylinders. It was horrible." he says. “So I went to the dealer's and bought a second one. I figured they couldn't have built anything that bad on purpose. But that second one was every bit as bad as the first one. So I bought this Wing. I’ve had it ever since."

The Honda Gold Wing in question is a 1975 GLI000, 'and what’s unusual about Sale's Wing is not that he's put 300.800 miles on it since he bought it new. It's that Sale, a bookbindery technician who says he's “on the wrong side of 50." and who lives near Toronto, Canada, has done a good many of those miles with a trailer in tow.

Now, we’re not talking some wimpy little touring-bike camp trailer. Sale's idea of a proper trailer depends on his activity-of-themoment. If he wants to trek to Nova Scotia, say. to go sailing, he hooks up the rig containing his 15-foot sailboat.

And if he wants to go racing, he hooks up the one upon which he hauls his short-track and speedway bikes. “If you're gonna go to a bike race, what better way to go than on a bike?" he asks.

Sale says that in spite of the miles on his bike, he has no plans to replace it with a newer example. That's because. he savs. of the incredible ser-

vice this bike has provided. He's had the engine apart once for bearings, rings and waterpump seals—no valve job was necessary—and every 12.000 miles or so he spoons new tires onto the bike. He's installed a Windjammer III fairing as a sort of concession to the weather, he's installed a hitch, of course, he's hung a set of driving lights on it. and he’s replaced the bike's original wire wheels—which disintegrated on account of road-salt-induced cancer—with a pair of Lester alloy wheels. Finally. Sale changes the bike's oil and filter every 3000

miles to help insure the engine's long life.

Sale dismisses the bike's high mileage with a so-what shrug of the shoulders, just as he dismisses the thought that riding in Canada's cold, snowy weather might be difficult. It isn't, he says. “I just adjust my riding techniques to match the weather conditions," he explains. What he'd rather talk about are the reactions he gets from people who can't believe his trailers.

“The people in cars, they shake their heads, and say. Ah, crazy motorcyclist.’ Truck drivers, they blow their horns, give me the thumbs-up: they understand towing a trailer. And other bike riders, well, that’s the most fun of all. You pass them and you wave, then you look in the mirror and check their reactions as the trailer goes by. They're amazed, totally astonished. It’s fun."

Sale sheepishly admits to owning a car, which he says he uses only on the five or six days when the weather is just too awful to ride in.

He says. “What with the price of gas. I'm gonna ride. Why not?”

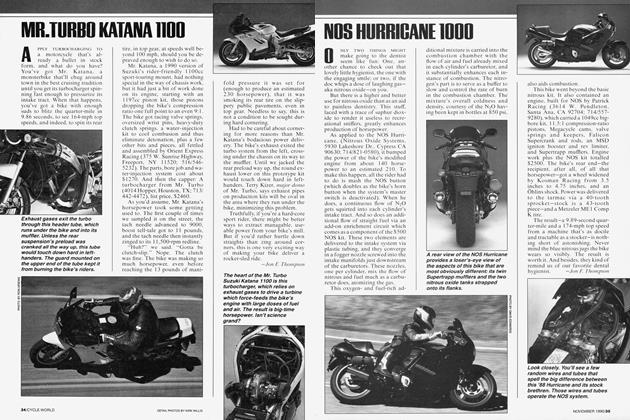

Eiti~V ii~is

1972 Norton Commando; 151,000 miles

EATS there a nutcase more warped than a true British-bike believer? Gerry Reynolds should know, because his bike has occasionally given him cause to doubt the wisdom of its purchase.

“I longed for it in my college days,” he says of his Norton 750, “but five years after I bought it, when British bikes weren’t worth what they are today, I asked myself why I ever paid that much money for this piece of junk.”

But today, as Reynolds sits back and eyeballs his brilliant blue Norton, he doesn’t see junk. He sees an old friend, a gorgeous piece of postwar British engineering. And he appreciates it.

The bike is a 1972 Commando Interstate, which Reynolds bought in 1973 for the then-whopping total of $1200. What makes the bike really special is that Reynolds has put 151.000 miles on it. Not a particu-

larly amazing number, perhaps, when applied to any of the modern touring appliances. But on a British Twin, of all things? It’s a bunch, a number of special significance, and it has wrought in Reynolds a change in attitude. Reynolds, 41, of Pacific Grove, California, a product engineer for a company that manufactures high-tech electronics components, now respects what he once thought of as low-tech garbage.

Though he owns other motorcycles, Reynolds estimates he still puts 10,000 miles per year on the old Norton, though he admits his rides have not been trouble-free. It has stranded him a couple of times, he says, and in the course of his relationship with the bike, he’s done lots of engine work, including a number of top-end rebuilds. He’s also replaced the original transmission with a Quaife fivespeed and shelved the stock ignition in favor of an electronic system.

Now, at least a temporary end seems in sight. “It’s nearly worn out,” Reynolds admits. “The crank’s never been ground, and it's got about a quarter-inch of end-float. The engine’s really tired. Still. I just get on it, kick it. and go,” he says reflectively, “and it’s a plush bike to ride. You can sit all day in the saddle; it feels like an FJ 1 200.”

In addition to its well-worn engine, the bike sustained damage in one of northern California’s numerous earthquakes. Sitting on its centerstand in Reynold's office parking lot, the Norton fell over in a temblor, and the left side of its Don Vesco Rabid Transit fairing was damaged. That, as much as anything, has temporarily removed the bloom from the Norton’s rose. Reynolds plans to repair the fairing and transfer it to his 850 Commando. Then he’ll get serious. Slowly, carefully, he’ll rebuild the 750. And he’ll install a set of Norton Fastback body parts he’s kept sequestered in his garage. And presto! Instant classic British supersport bike, just the sort of thing to keep a true Bnt-bike believer entertained for another 1 7 years.

J~SS~ 1988 HarIey~Davidson Electra Glide 135,000 miles

-I~ L VERCRUYSSE CAME LATE to the road. but when he came, he came very seriously in deed. He had lived for Gloria. his wife, whom he wed in 194 1. She was a muscular dystrophy patient. and she spent the final 22 v ears of her bout with the crippling disease in a wheelchair. In 1975 she died. Two years later. Ver( `ruvsse discovered motorcycles. He discovered, specifically. Har ley-Davidsons. "For one thing. I'm an old American." he explains, "I hu~ American as much as I can. And for another. Harley-I)avidson . builds a perfectly oood bike."

And VerCruvsse should know. In just over 13 years. he's ridden 458.000 miles. And he's done the last 135,000 on his 1988 Electra Glide. his fIfth in a long string of Harleys. This one is a replacement for his 1984 FLHTC. severely damaged when a tire blew at speed. "That was the only reason I turned it in." he says. "and Fd already put 188.000 miles on it. His purpose in riding. VerCruvsse says, is to "Ride for the heck of it. I visit people. and I promote good will for the Muscular Dystrophy Associa tion. I started riding when I was 6 I. decided I couldn't start any younger. I got the urge to ride a bike. SO I bought one." .And. he adds, "People tell me I'm absolutely crazy. Then they say. l wish I had the nerve to do it.' I tell them it's all in the mind." But VerCruysse. a car •~ penter prior to his re tirement. doesn't long-distance riding as his primary pur pose in life. That position he reserves

for the MDA. He says. "The kids, the people-theyre just my purpose for living. I think. I go around and tell people about the association, and I thank them for helping us. I speak at motorcycle club meetings. health classes in high schools, at service club meetings. things like that. It's just a way of life for me. I don't know what else I'd do if I didn't have that to do." VerCruysse is convinced Gloria not only would have approved of his riding. hut that "she probably would have enjoyed riding with me. Motor cycling was always supposed to be an awfully dangerous pastime. you know. Now. I realize that the danger is overrated. It's all in how reckless or how careful you are." Ver('ruvsse is very careful, hut still. he's been down three times, in cluding the incident of the blown tire. "Got scratched up a little, noth ing serious." he recounts. And he says. "Mv goal now is a half-million miles by September 13. 1991. lhat'll he my 75th birthday. And it'll he just over So years I'll have been working with muscular dystrophy. I'm a man with goals. And OflC of those is to put at least 200.000 miles on his current bike. "The hike's been great." he says. "I' `~ e had no motor work done on it. If it needs work, I'll have it done, and t keep As long as I can keep the shiny side up.

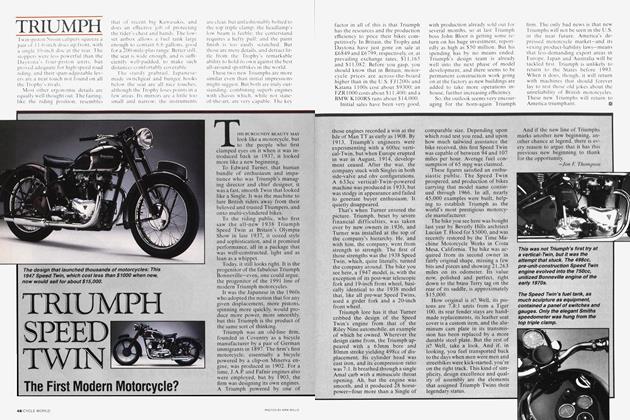

I?4:N

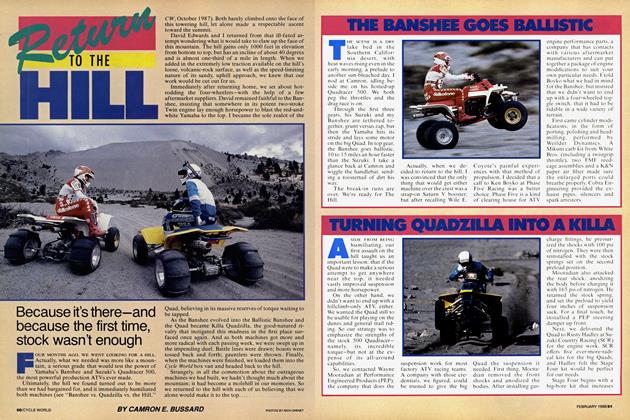

1 974 Kawasaki Hi 40,000 miles

'"Y"'EVER MINI) WH AT S TA N Henriksen’s trusty Kawasaki looks like. That toasting is purely temporary, the result of some nasty little neighborhood vandals with more time on their hands than was good for them. Using that time, they incinerated Henriksen’s bike, which was parked outside his home. Such a disaster might discourage some motorcyclists. but not Henriksen. 36, of Ashburn, Virginia, who describes himself as “a computer guy.” He’s also a weekend dragster, and says of his krispy Kaw. “It’s gonna see the racetrack again. It’s too good a bike to get rid of.”

Which might seem, to some of us, a decision of questionable merit.

This is. after all. a 1974 Kawasaki HI, the infamous.

500cc two-stroke Triple reputed to combine a horsepower hit as abrupt as a whack from a

9-pound sledge with handling that can only be called diabolical. But Henriksen doesn’t want to know; he actually cherishes the beast, acquired second-hand in I 976 from its original owner, who, with great wisdom after putting 1248 miles on the bike and laying it down at least twice in that short time, decided it might not be the ideal entry-level ride. Henriksen got the bike for $700. A steal.

He immediately whipped clip-ons.

rearsets and struts onto the bike, then pumped-up the motor with TNT expansion chambers and modified pistons. modifications that yielded. Henriksen says with considerable glee. “Seventy horsepower. Yahoo!” Next came wider wheels, a slick rear tire and an extended swingarm, and the H 1 was fully armed as a bracket racer. But there’s more to a week than weekends, so evenings were spent in what Henriksen calls “running the ridges,” which means, ahem, street racing. Over the next 10 years, 40,000 miles were logged on the Tri-

ple, mostly in short, violent quartermile bursts.

To keep the old H 1 healthy, each winter it got new rings, new top end, a new crank—work made easy to afford, Henriksen says, because “in the late 1 970s. any 111 could be had (as a parts bike) for $ 1 00.”

New members of Henriksen’s 15bike stable came and went, and a wife arrived, a seminal event which relegated the by-now tired old stroker to the back of the garage. Then, along about 1986, wedded bliss reverted to solitary satisfaction.

A top priority? Recover the HI, refurbish it and re-register it as a full-on streetbike.

Says the bike's owner, “Watching my younger riding buddies get off GPzs and FJs and try to come to terms with a ported ^o-stroke was

worth the wait, especially when they tried to push (no kick-starter here) life back into it.”

Putting life back into the bike has. in the wake of recent events, special urgency for Henriksen, who allows, “Fresh paint won't hide the flaws after all these years. After all. the bikes of today are light-years ahead of my old HI. Still, the lessons learned from trial and error and sweat made motorcycling what it is to me today. Now. if I can just find another used HI. That, some paint and tires, and I'll be set.” Set. it would now appear, to make the toasty old Kawasaki as sweet as jam.

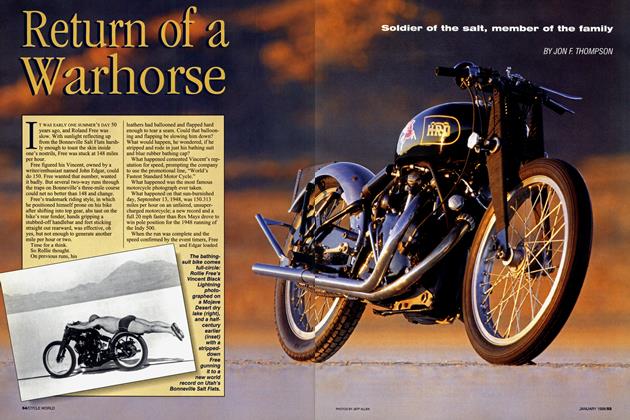

I~JJJ~ 1975BMW R60/6 750,000 miles

HREE-QUARTERS OF A MILlion miles on one motorcycle0 Is this guy crazy, or what? "Well," says Karl Szobody, Denver-area snow-plow driver, thinking for a moment, "I’ve been called crazy. But that’s been for riding to work during big storms. Mostly. I just like riding."

Indeed. And what he likes to ride is his 1975 BMW R60/6, which he bought new and has been riding ever since. "The thing is probably the most reliable bike an the road." allows Szobody. "In fact." he continues, "I'm sure it is."

That mileage figure is a real one. insists Szobody, 48. "Ask anyone who knows the bike. Ask my me-

chanic. Ask my attorney." he suggests.

Okay, okay, we believe it; we’d just as soon not talk to an attorney for any reason, thanks just the same. But the question remains, why, at a time when bikes have gotten so much better over so short a period of time, so many miles on so old a bike?

"I don't know. I had other bikes— Ducatis. Hondas. Harleys, Indians— but I always wanted a BMW." Szobody explains. Once acquired, the little black Beemer was put into almost constant service.

A 400-mile ride for an after-work cup of coffee? No problem. Every BMW Owners' Club rally for the last 12 years, at locations in every corner of the USA? No problem. Depart Denver on a Sunday morning and arrive in Rutland, Vermont, the next day, 1948 miles later, stopping only for gas, snacks and an hour's rest? No problem. Go for rides, any time, all the time, no matter what kind of nasty weather the Denver area can throw at him? No problem.

Clearly, in all those miles, there have been lots of breakdowns and mechanical problems, rieht?

Nope.

Szobody changes the bike’s oil and filter every 1000 miles. That, he claims, has been enough to insure performance perfection.

"I did have a top-end job done at 100.000 miles; it didn't need it, somebody just told me it would be good preventive maintenance. So I did it. and haven't touched the bike since." he swears.

Except to whip the occasional set of tires on it. and to remove an electronic ignition system he installed, an item Szobody blames for the bike’s one mechanical let-down.

"It just cooked a coil, but since I've gone back to the stock system I've had no problems." he says.

Except from his wife, we suspect, from whom he must be absent to do all that riding?

"She's accused me of loving the bike more than I do her," Szobody admits, “but I've been married more than 27 years, so it's not true."

Nevertheless, so attached has Karl Szobody become to his BMW that he's given it a pet name. Misty Black, he calls it. Talks to it on long trips, he admits.

So is Karl Szobody crazy? Naw. Just crazy about riding. And about the long-term magic of Boxer Twins. E3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontAscot Eulogy

February 1991 By David Edwards -

At Large

At LargeDoin' the Norton Rap

February 1991 By Steven L. Thompson -

Leanings

LeaningsLetters From the World

February 1991 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1991 -

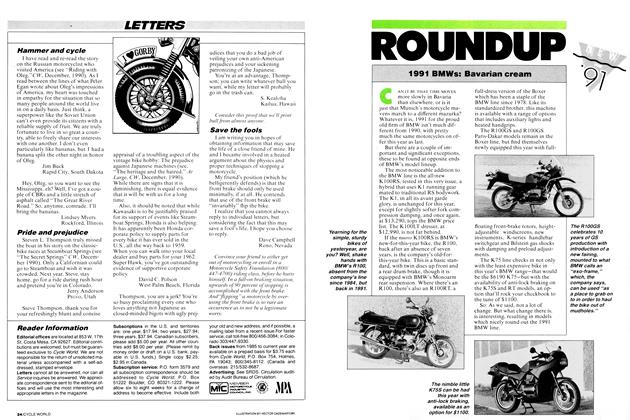

Roundup

Roundup1991 Bmws: Bavarian Cream

February 1991 -

Roundup

RoundupCzeching Out Jawa

February 1991 By Pavel Husák