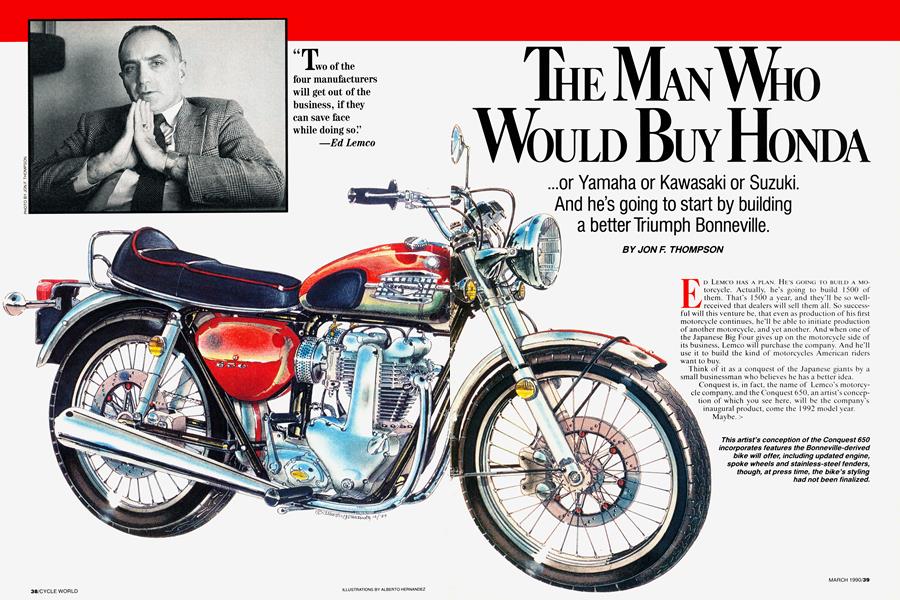

THE MAN WHO WOULD BUY HONDA

...or Yamaha or Kawasaki or Suzuki. And he's going to start by building a better Triumph Bonneville.

JON F. THOMPSON

ED LEMCO HAS A PLAN. HE'S GOING TO BUILD A MOtorcycle. Actually, he's going to build 1500 of them. That's 1500 a year, and they'll be so well-received that dealers will sell them all. So successful will this venture be, that even as production of his first motorcycle continues, he'll be able to initiate production of another motorcycle, and yet another. And when one of the Japanese Big Four gives up on the motorcycle side of its business, Lemco will purchase the company. And he'll use it to build the kind of motorcycles American riders want to buy.

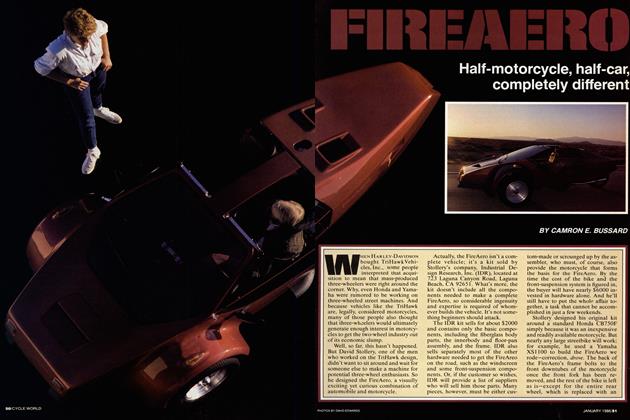

Think of it as a conquest of the Japanese giants by a small businessman who believes he has a better idea. Conquest is, in fact, the name of Lemco’s motorcycle company, and the Conquest 650, an artist’s conception of which you see here, will be the company’s inaugural product, come the 1992 model year. Maybe. >

The Conquest 650. the two-wheeled building block with which Lemco plans to build Conquest Motors, the boot which will hold the manufacturing door open for him, is based on a concept which might be described as “Forward into Yesterday.” It will be based upon the nowdefunct, Les Harris-built Triumph Bonneville. But the various components will be modified and upgraded so that the bike will be much more than what Lemco calls “a warmed-over Triumph.” The Conquest 650 will be an allnew bike, Lemco says, one aimed at a buyer who these days seems convinced, in Lemco’s words, that. “You meet the nicest people on a Harley.”

Lemco, 45, of Albany, Oregon, is a former motorcycle and auto dealer who in the early 1980s formed The American Dealer Group, of which he is executive director. The ADG is a management firm organized to help dealers find ways to make their operations more effective and profitable. It is composed of 164 dealers, people Lemco calls “the very best motorcycle dealers in America,” because, he says, while the group comprises only two percent of the total number of dealers, it sells, he claims, 25 percent of all the motorcycles sold each year.

What his dealers were telling him is that in spite of generally slow motorcycle sales, there are motorcycle buyers out there. The problem, Lemco says, is that nobody is building the motorcycles those buyers want: a simple, robust, easy-to-work-on vertical-Twin.

“These guys are 40 to 60 years old, and they don't identify with the product that’s out there. They don't want to go 140 miles per hour,” explains Lemco. The motorcycle they want, he believes, is something like a Yamaha XS650 Twin, long out of production. Or even better, they'd like a bike like that, but built in Britain or the United States.

The buyer’s wife figures into this, too, Lemco believes. Current offerings from the Japanese aren’t selling well, Lemco’s dealers tell him, because, “The wife says, 'I don’t want him to have a racing machine.’ It’s the wife who’s selling the Harley. It’s perceived as safer because it doesn’t look like it goes as fast.”

In any case, Lemco undertook talks with Japanese, French and Italian manufacturers. He asked them to dust off old designs, ones which older riders could relate to, and resume production. There seems to be some interest there, Lemco says, and the talks continue.

But meanwhile, Lemco heard of Les Harris, of L.F. Harris Rushden Ltd., in South Devon, England. Harris, who built the last batch of Bonnevilles under license and who also builds the Rotax-powered Matchless G80 (see “Quick Ride,” CW, July, 1989), has a 40,000-square-foot motorcycle factory, a few core workmen and ownership of a some key motorcycle component designs that would form, Lemco believes, exactly the motorcycle his dealers could sell. And, better yet, Harris was itching to build exactly the motorcycle Lemco wanted.

“When Lemco came and saw us, we were over the moon. He was just what we were looking for.” Harris told Cycle World in a telephone interview.

Like Lemco, Harris believes a market exists fora motorcycle built in the classic mold, and he just happened to have drawings for such a motorcycle.

So, in August of 1989, Lemco and Harris decided to build the bike, providing Lemco could raise the $4 million necessary to kick the project off. At press time, Lemco says he has obtained pledges from potential investors for about half the amount.

The Conquest 650 Harris will build will be a classic British vertical-Twin. but with a number of concessions to the onward march of technology. Because vertical-Twins vibrate, the Conquest’s engine will have counterbalancer shafts. And because Lemco believes part of the classic allure is a kick starter, the Conquest will have one. But it will also have an electric starter. It'll have spoked wheels, alloy rims, a disc brake on each wheel, tube-type tires and twin-shock rear suspension. It will be air-cooled, but it will have an overhead cam and four valves per cylinder.

“It’ll be state-of-the art. It doesn’t have to be multicylindered and electric-gizmoed to be state-of-the-art,” Lemco insists.

Still, at press time, nobody knows for sure what the Conquest will look like, because the bike’s styling has not been finalized. When asked about the bike's look, Harris would only say, “I like the Triumph tank; it’s quite a nice tank. But a Matchless-styled tank also would look nice.” Lemco’s target price has been $5000, though he concedes that number may climb to $5300 before the bike finally is introduced in late 1991.

Providing he can find the financing to initiate production, pass emissions and noise testing and obtain product liability insurance—and Lemco says none of these matters present insurmountable problems—the 164 dealerships now a part of the ADG will be the core dealers of Conquest Motors. Lemco says he’d like to see the total dealer number rise to 300. Dealers can invest in the project with a minimum outlay of $ 10,000, but they don't have to invest in the Conquest to sell it, and Lemco continues his search for investors outside the dealer body.

“T

At’llbe state-of-the-art. It doesn’t have to be multi-cylindered and electric-gismoed to be state-of-the-art!’

As Lemco envisions things, to buy a Conquest 650, a buyer will visit a Conquest dealership and place his order. The bike will be built to that order with the buyer’s name affixed to its chassis, and it will be delivered with a certificate signed by the craftsmen who assembled it.

Because of considerable interest in Europe, Britain, Australia and Japan in classic motorcycles, both Lemco and Harris believe they'll have no trouble at all selling 1 500 Conquest 650s a year. And this is where things start to get interesting.

Having established a dealer-driven motorcycle company, one based on a direct factory-to-consumer network which eliminates the 35 percent distributorship costs he claims are responsible for high motorcycle prices in the U.S., Lemco believes he’ll then be perfectly positioned for the big break. He believes that in three to five years, he'll be able to make a stock offering so that Conquest Motors will become a public company. But more importantly, he believes that in another few years beyond that, “There’s going to be a significant window of opportunity, and we want to be in a position to step through it.”

That window will open, Lemco says, when one or more of the Japanese companies now selling motorcycles in the United States elects to bail out of its motorcycle operations.

And this is the core of the gospel according to Ed Lemco: “The Japanese are not emotionally in the motorcycle business. They’re huge, multinational conglomerates that happen to still be in the motorcycle business. But (in this business) emotional commitment is everything.” Because he believes that their commitment is lacking, and because he believes the Japanese companies are out of touch with the motorcycle market, Lemco also believes that, “Two of the four manufacturers will get out of the business, if they can save face while doing so. It’s my belief we might be able to put together that option, and the Conquest 650 is the starting point.”

When contacted by Cycle World, representatives of three of the Japanese manufacturers said they could foresee no circumstances under which their companies would sell off American motorcycle operations. A representative of the fourth said only that he didn’t wish to respond to speculation.

Industry observer Don Brown, of D.J. Brown Associates, also questions Lemco’s plan.

“I’m skeptical about the whole concept,” he said. “There’s a feeling that what we need is a simple, straightforward, standard motorcycle, but Honda tested those waters with the Hawk. I thought it would do very well, but it didn’t. It sells, but in modest numbers. I find it very hard to believe that the industry’s problems are going to be solved by merely going back in time.”

Lemco admits his plan is a gamble, but sees circumstances in his favor. With the motorcycle population getting older, with interest in classic bikes high, with the current backlash against high-tech, repli-racers and with a manufacturing company’s assembly lines, tooling, jigs and personnel already in place, he believes the time is right for the birth of another motorcycle company.

Whether or not Lemco’s vision comes true, whether or not he gets to prove, as he likes to say, that “we can eat with the big dogs,” is at best uncertain. Motorcycling’s history is littered with good dreams turned to dust. But for now, Ed Lemco has the key ingredients that all great automotive giants—from Henry Ford to William Harley and the Davidson brothers to Soichiro Honda—displayed: a strong belief in his product and a stronger belief in himself.

Time will tell if that is enough. M

View Full Issue

View Full Issue