THE CW LIBRARY

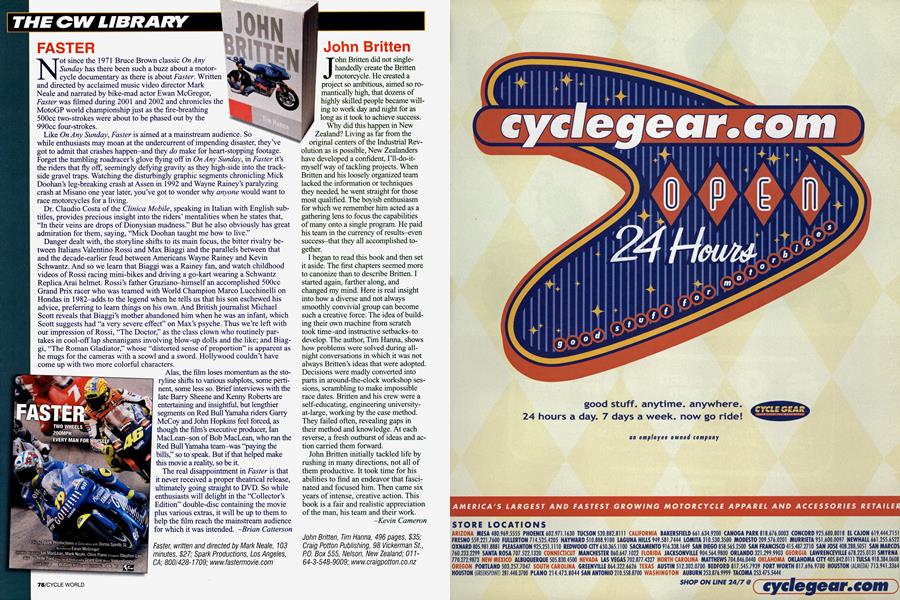

FASTER

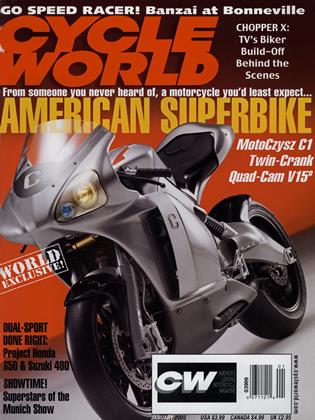

Not since the 1971 Bruce Brown classic On Any Sunday has there been such a buzz about a motorcycle documentary as there is about Faster. Written and directed by acclaimed music video director Mark Neale and narrated by bike-mad actor Ewan McGregor, Faster was filmed during 2001 and 2002 and chronicles the MotoGP world championship just as the fire-breathing 500cc two-strokes were about to be phased out by the 990cc four-strokes.

Like On Any Sunday, Faster is aimed at a mainstream audience. So while enthusiasts may moan at the undercurrent of impending disaster, they’ve got to admit that crashes happen-and they do make for heart-stopping footage. Forget the tumbling roadracer’s glove flying off in On Any Sunday, in Faster it’s the riders that fly off, seemingly defying gravity as they high-side into the trackside gravel traps. Watching the disturbingly graphic segments chronicling Mick Doohan’s leg-breaking crash at Assen in 1992 and Wayne Rainey’s paralyzing crash at Misano one year later, you’ve got to wonder why anyone would want to race motorcycles for a living.

Dr. Claudio Costa of the Clinica Mobile, speaking in Italian with English subtitles, provides precious insight into the riders’ mentalities when he states that, “In their veins are drops of Dionysian madness.” But he also obviously has great admiration for them, saying, “Mick Doohan taught me how to live.”

Danger dealt with, the storyline shifts to its main focus, the bitter rivalry between Italians Valentino Rossi and Max Biaggi and the parallels between that and the decade-earlier feud between Americans Wayne Rainey and Kevin Schwantz. And so we learn that Biaggi was a Rainey fan, and watch childhood videos of Rossi racing mini-bikes and driving a go-kart wearing a Schwantz Replica Arai helmet. Rossi’s father Graziano-himself an accomplished 500cc Grand Prix racer who was teamed with World Champion Marco Lucchinelli on Hondas in 1982-adds to the legend when he tells us that his son eschewed his advice, preferring to learn things on his own. And British journalist Michael Scott reveals that Biaggi’s mother abandoned him when he was an infant, which Scott suggests had “a very severe effect” on Max’s psyche. Thus we’re left with our impression of Rossi, “The Doctor,” as the class clown who routinely partakes in cool-off lap shenanigans involving blow-up dolls and the like; and Biaggi, “The Roman Gladiator,” whose “distorted sense of proportion” is apparent as he mugs for the cameras with a scowl and a sword. Hollywood couldn’t have come up with two more colorful characters.

Alas, the film loses momentum as the storyline shifts to various subplots, some pertinent, some less so. Brief interviews with the late Barry Sheene and Kenny Roberts are entertaining and insightful, but lengthier segments on Red Bull Yamaha riders Garry McCoy and John Hopkins feel forced, as though the film’s executive producer, Ian MacLean-son of Bob MacLean, who ran the Red Bull Yamaha team-was “paying the bills,” so to speak. But if that helped make this movie a reality, so be it.

The real disappointment in Faster is that it never received a proper theatrical release, ultimately going straight to DVD. So while enthusiasts will delight in the “Collector’s Edition” double-disc containing the movie plus various extras, it will be up to them to help the film reach the mainstream audience for which it was intended. -Brian Catterson

Faster, written and directed by Mark Neale, 103 minutes, $27; Spark Productions, Los Angeles, CA; 800/428-1709; www.fastermovie.com

John Britten

John handedly Britten create did not the singleBritten motorcycle. He created a project so ambitious, aimed so romantically high, that dozens of highly skilled people became willing to work day and night for as long as it took to achieve success.

Why did this happen in New Zealand? Living as far from the original centers of the Industrial Revolution as is possible, New Zealanders have developed a confident, I’ll-do-itmyself way of tackling projects. When Britten and his loosely organized team lacked the information or techniques they needed, he went straight for those most qualified. The boyish enthusiasm for which we remember him acted as a gathering lens to focus the capabilities of many onto a single program. He paid his team in the currency of results-even success-that they all accomplished together.

I began to read this book and then set it aside. The first chapters seemed more to canonize than to describe Britten. I started again, farther along, and changed my mind. Here is real insight into how a diverse and not always smoothly convivial group can become such a creative force. The idea of building their own machine from scratch took time-and instructive setbacks-to develop. The author, Tim Hanna, shows how problems were solved during allnight conversations in which it was not always Britten’s ideas that were adopted. Decisions were madly converted into parts in around-the-clock workshop sessions, scrambling to make impossible race dates. Britten and his crew were a self-educating, engineering universityat-large, working by the case method. They failed often, revealing gaps in their method and knowledge. At each reverse, a fresh outburst of ideas and action carried them forward.

John Britten initially tackled life by rushing in many directions, not all of them productive. It took time for his abilities to find an endeavor that fascinated and focused him. Then came six years of intense, creative action. This book is a fair and realistic appreciation of the man, his team and their work.

-Kevin Cameron

John Britten, Tim Hanna, 496 pages, $35; Craig Potton Publishing, 98 Vickerman St., PO. Box 555, Nelson, New Zealand; 01164-3-548-9009; www.craigpotton.co.nz

View Full Issue

View Full Issue