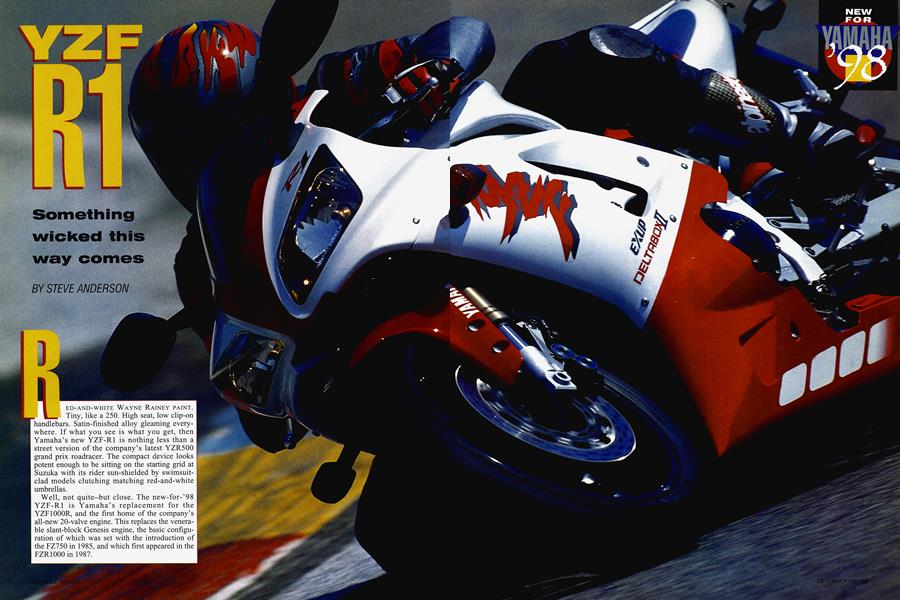

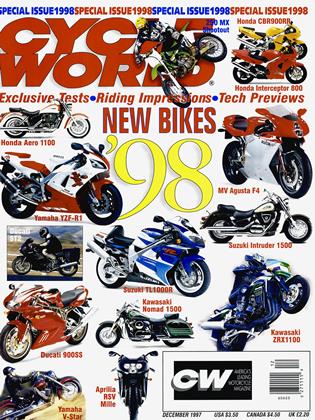

YZF R1

Something wicked this way comes

STEVE ANDERSON

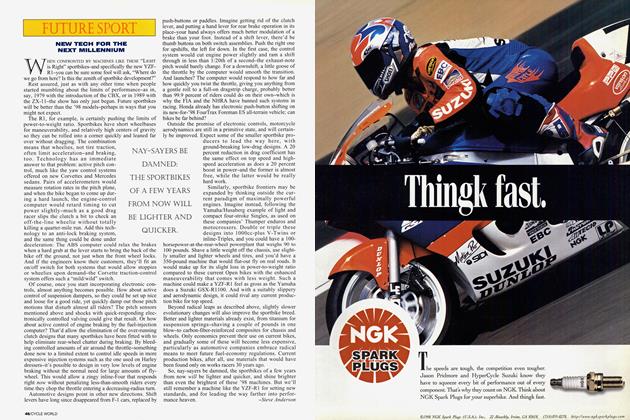

RED-AND-WHITE WAYNE RAINEY PAINT. Tiny, like a 250. High seat, low clip-on handlebars. Satin-finished alloy gleaming everywhere. If what you see is what you get, then Yamaha’s new YZF-R1 is nothing less than a street version of the company’s latest YZR500 grand prix roadracer. The compact device looks potent enough to be sitting on the starting grid at Suzuka with its rider sun-shielded by swimsuitclad models clutching matching red-and-white umbrellas.

Well, not quite-but close. The new-for-’98 YZF-R1 is Yamaha’s replacement for the YZF1000R, and the first home of the company’s all-new 20-valve engine. This replaces the venerable slant-block Genesis engine, the basic configuration of which was set with the introduction of the FZ750 in 1985, and which first appeared in the FZR1000 in 1987.

NEW FOR YAMAHA '98

The tuning-fork company’s goal was simple: Smash Honda’s CBR900RR, the best-selling sportbike in the thriving European market ever since its introduction in 1992. To fully compete with the short and light CBR, Yamaha realized that its new bike must be at least as compact as the Honda, equally racy-and far more powerful.

That required a thorough re-think of the powerplant. The first Genesis engine was revolutionary, what with its five-valve-per-cylinder heads, jackshaftmounted alternator, 45-degree inclined cylinders and downdraft carburetors. But like most revolutions, not all parts were equally successful. In particular, the laid-down cylinders proved to be an idea pushed to the extreme, placing the heavy crankshaft and transmission too far aft. This situation was first corrected by Bimota, which rotated the entire FZ750 engine more upright in its 1987 Formula 1 World Championship-winning YB4. This decision was quickly followed by Yamaha with the first re-do of the FZR1000 in 1989. Both companies made the change simply by rotating the powerplant upward in the chassis, the only difference in the engine being a new oil pan. But with the Rl, for the first time in 12 years, Yamaha’s engineers started with a clean sheet of paper, free to keep the best of the Genesis revolution-and dispose of the worst.

The new engine retains Yamaha’s signature five-valve design, though the valve angles have been steepened by 2.75 degrees to create an even more compact combustion chamber-the third such alteration since 1985. With smaller and lighter forged pistons, the new engine boasts cylinder dimensions of 74 x 58mm, making it slightly more undersquare than the 75 x 56mm of the previous YZF 1000. But the most significant changes are in the engine packaging: The cylinders are now more upright, and the cam drive, previously located in the center, has moved to the right end of the crankshaft, allowing evenly and more closely spaced cylinders and carburetors. Though the carb throats now measure 40mm, the carb assembly spans almost 1.25 inches less than last year, allowing a similar decrease in fuel tank and frame width. The new six-speed transmission has been crammed into the least possible length, with the clutch and layshaft mounted high, and the countershaft almost directly underneath. Following Honda’s lead, the cylinders are now integrated into the upper case casting, with the cylinder running surface an electrocoating on aluminum. Even the water-pump location has been chosen with compactness in mind; it’s buried inside the cases, driven on the same shaft as the oil pump. The jackshaft-mounted alternator also gave way to save weight and space; it’s now on the left end of the crank, while improved materials and design keep it small so as not to reduce cornering clearance.

At first glance, the new engine looks like an old YZF motor rear-ended by a truck. It’s 3.2 inches shorter and, at 166 pounds in weight, 23 pounds lighter. If Yamaha’s claims can be believed, that makes the YZF engine 2 pounds lighter than that of the CBR900RR, and 1 pound lighter than Suzuki’s GSX-R750 engine. And with its compression ratio boosted to 11.8:1, its valve stems narrowed from 4.5 to 4mm to boost flow, and its rpm capabilities raised through the use of forged pistons and lighter connecting rods, the Rl engine makes a claimed 150 horsepower at the crank-which, if true, should put around 130 horses to the rear wheel, for a sizable, 56hp increase over the last YZF1000 this magazine tested.

Of course, the chassis carrying the engine is just as new. The stated Yamaha design goal was to build the ultimate mountain-road bike, not the ultimate racetrack bike, but only a few differences distinguish the two. The wheelbase has been shortened to 54.9 inches, less than most 600cc sportbikes and roughly the same as a 500cc GP bike. The new frame, according to Yamaha, isn’t as stiff as one designed solely for the track, but instead was carefully designed for controlled flex and weight efficiency. Along with that, both the inverted fork and the single rear shock provide 5.3 inches of travel, slightly more than required for a pure racer-replica.

Other details of the chassis speak to the performance focus, and the need to keep the weight low. The steering head uses ball bearings instead of tapered rollers, an aluminum steering stem and motocross-type single-lip seals. As well as saving weight, says Yamaha, the new design cuts friction and improves steering feel. The battery has shrunk by 2 amphours to a 10 amp-hour design. Thanks to the short engine, even with the shortened wheelbase, the swingarm could grow particularly long, and the countershaft location and swingarm angle have been chosen to optimize the anti-squat geometry of the rear suspension-something that teams racing YZF750-based Superbikes have struggled with for years. The swingarm is no longer a unitized sheetmetal diamond in side-view, but instead is an extruded beam braced with a truss across the top. The front brake calipers have been simplified and lightened, and the torque arm dropped from the rear disc brake for weight

savings. Even the exhaust system has been scrutinized for ounces, with tubing thickness cut by .008-inch, and the muffler fabricated from carbon-fiber-covered aluminum.

The payoff, according to Yamaha, is a full-up wet weight of 437 pounds, the lightest of Open-class sportbikes. If Yamaha’s dyno and scales are even close to accurate, the Rl’s power-to-weight ratio may well be the best in motorcycling, potentially rivaled only by the other new-for’98 Open-classers. This is a machine that promises to run low-10-second quarter-miles and push 170 mph in top speed.

If there’s any trade-off to the new performance, it’s a sharpening of focus. The seat height is about an inch higher than on previous YZFs, and the bars are lower and narrower. The new fairing may look great and reduce drag by more than 6 percent, but it’s also 3 inches lower than that of the YZF1000, and even Yamaha representatives who have ridden the bike indicate it doesn’t offer much in the way of wind protection unless you’re tucked in a roadrace crouch. One look at the high-mounted passenger pegs will tell you that riding two-up was about as high on the designers’ list of priorities as fuel economy.

But there are other machines for those who want their performance diluted with a larger dash of comfort and utility. Yamaha is building this bike for riders who want nothing less than the quickest, fastest, lightest, best-handling sportbike they can find, and damn the consequences. For the moment, everyone else attempting to build the ultimate sportbike can consider the ante upped.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue