Triumph and the Fates

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

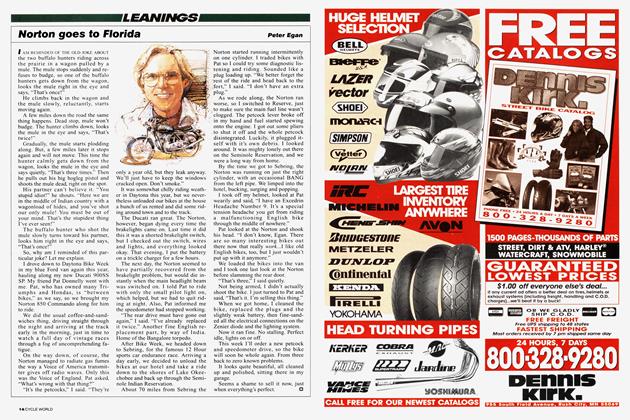

YOU’D THINK BY NOW IT WOULD BE Axiomatic never to compliment a British bike on its reliability, even in the mind, much less with the spoken or written word. But sometimes one forgets.

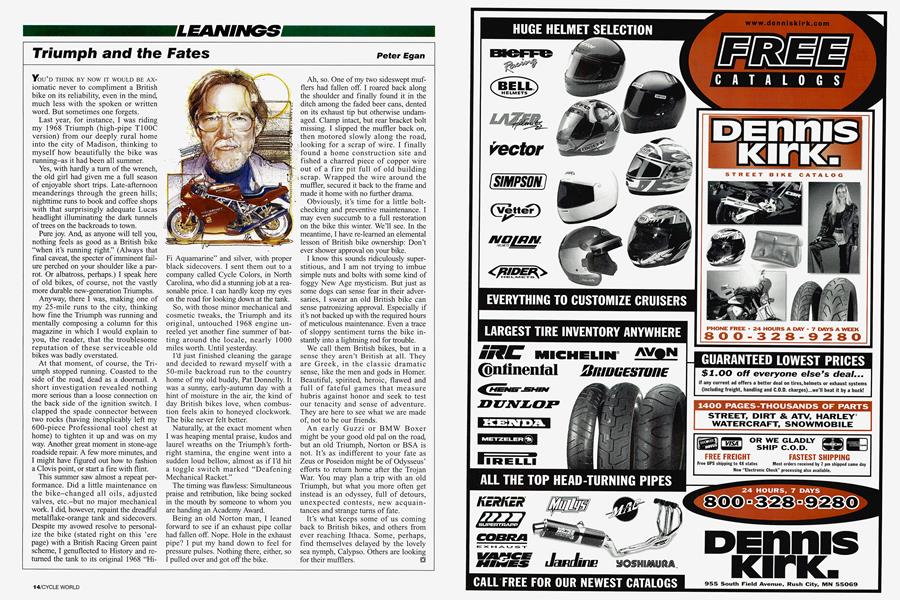

Last year, for instance, I was riding my 1968 Triumph (high-pipe T100C version) from our deeply rural home into the city of Madison, thinking to myself how beautifully the bike was running-as it had been all summer.

Yes, with hardly a turn of the wrench, the old girl had given me a full season of enjoyable short trips. Late-afternoon meanderings through the green hills; nighttime runs to book and coffee shops with that surprisingly adequate Lucas headlight illuminating the dark tunnels of trees on the backroads to town.

Pure joy. And, as anyone will tell you, nothing feels as good as a British bike “when it’s running right.” (Always that final caveat, the specter of imminent failure perched on your shoulder like a parrot. Or albatross, perhaps.) I speak here of old bikes, of course, not the vastly more durable new-generation Triumphs.

Anyway, there I was, making one of my 25-mile runs to the city, thinking how fine the Triumph was running and mentally composing a column for this magazine in which I would explain to you, the reader, that the troublesome reputation of these serviceable old bikes was badly overstated.

At that moment, of course, the Triumph stopped running. Coasted to the side of the road, dead as a doornail. A short investigation revealed nothing more serious than a loose connection on the back side of the ignition switch. I clapped the spade connector between two rocks (having inexplicably left my 600-piece Professional tool chest at home) to tighten it up and was on my way. Another great moment in stone-age roadside repair. A few more minutes, and I might have figured out how to fashion a Clovis point, or start a fire with flint.

This summer saw almost a repeat performance. Did a little maintenance on the bike-changed all oils, adjusted valves, etc.-but no major mechanical work. I did, however, repaint the dreadful metalflake-orange tank and sidecovers. Despite my avowed resolve to personalize the bike (stated right on this ’ere page) with a British Racing Green paint scheme, I genuflected to History and returned the tank to its original 1968 “HiFi Aquamarine” and silver, with proper black sidecovers. I sent them out to a company called Cycle Colors, in North Carolina, who did a stunning job at a reasonable price. I can hardly keep my eyes on the road for looking down at the tank.

So, with those minor mechanical and cosmetic tweaks, the Triumph and its original, untouched 1968 engine unreeled yet another fine summer of batting around the locale, nearly 1000 miles worth. Until yesterday.

I’d just finished cleaning the garage and decided to reward myself with a 50-mile backroad run to the country home of my old buddy, Pat Donnelly. It was a sunny, early-autumn day with a hint of moisture in the air, the kind of day British bikes love, when combustion feels akin to honeyed clockwork. The bike never felt better.

Naturally, at the exact moment when I was heaping mental praise, kudos and laurel wreaths on the Triumph’s forthright stamina, the engine went into a sudden loud bellow, almost as if I’d hit a toggle switch marked “Deafening Mechanical Racket.”

The timing was flawless: Simultaneous praise and retribution, like being socked in the mouth by someone to whom you are handing an Academy Award.

Being an old Norton man, I leaned forward to see if an exhaust pipe collar had fallen off. Nope. Hole in the exhaust pipe? I put my hand down to feel for pressure pulses. Nothing there, either, so I pulled over and got off the bike.

Ah, so. One of my two sideswept mufflers had fallen off. I roared back along the shoulder and finally found it in the ditch among the faded beer cans, dented on its exhaust tip but otherwise undamaged. Clamp intact, but rear bracket bolt missing. I slipped the muffler back on, then motored slowly along the road, looking for a scrap of wire. I finally found a home construction site and fished a charred piece of copper wire out of a fire pit full of old building scrap. Wrapped the wire around the muffler, secured it back to the frame and made it home with no further drama.

Obviously, it’s time for a little boltchecking and preventive maintenance. I may even succumb to a full restoration on the bike this winter. We’ll see. In the meantime, I have re-learned an elemental lesson of British bike ownership: Don’t ever shower approval on your bike.

I know this sounds ridiculously superstitious, and I am not trying to imbue simple nuts and bolts with some kind of foggy New Age mysticism. But just as some dogs can sense fear in their adversaries, I swear an old British bike can sense patronizing approval. Especially if it’s not backed up with the required hours of meticulous maintenance. Even a trace of sloppy sentiment turns the bike instantly into a lightning rod for trouble.

We call them British bikes, but in a sense they aren’t British at all. They are Greek, in the classic dramatic sense, like the men and gods in Homer. Beautiful, spirited, heroic, flawed and full of fateful games that measure hubris against honor and seek to test our tenacity and sense of adventure. They are here to see what we are made of, not to be our friends.

An early Guzzi or BMW Boxer might be your good old pal on the road, but an old Triumph, Norton or BSA is not. It’s as indifferent to your fate as Zeus or Poseidon might be of Odysseus’ efforts to return home after the Trojan War. You may plan a trip with an old Triumph, but what you more often get instead is an odyssey, full of detours, unexpected contests, new acquaintances and strange turns of fate.

It’s what keeps some of us coming back to British bikes, and others from ever reaching Ithaca. Some, perhaps, find themselves delayed by the lovely sea nymph, Calypso. Others are looking for their mufflers.