Honda at 50

UP FRONT

David Edwards

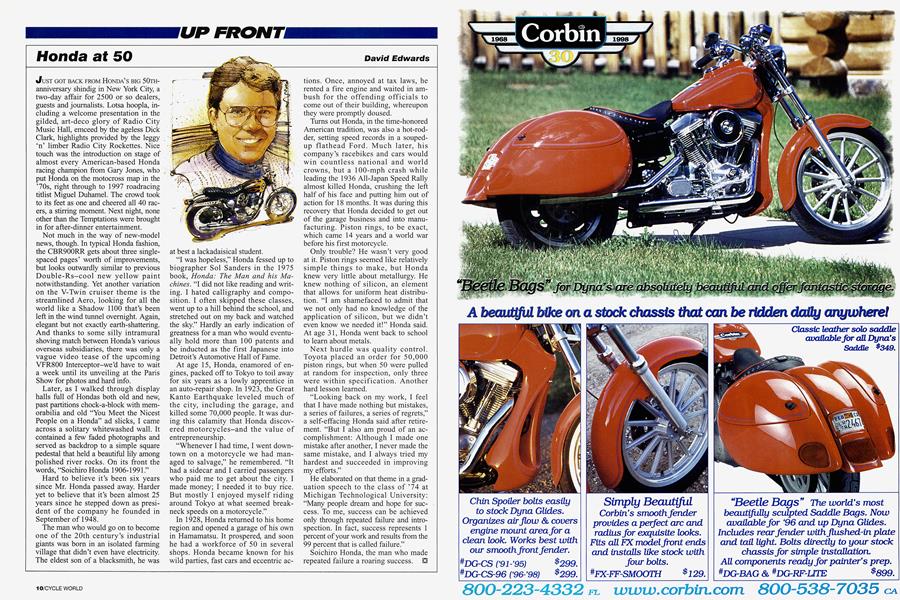

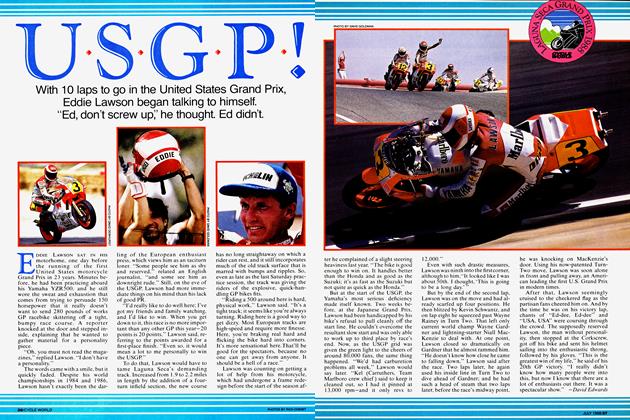

JUST GOT BACK FROM HONDA’S BIG 50TH-anniversary shindig in New York City, a two-day affair for 2500 or so dealers, guests and journalists. Lotsa hoopla, including a welcome presentation in the gilded, art-deco glory of Radio City Music Hall, emceed by the ageless Dick Clark, highlights provided by the leggy ‘n’ limber Radio City Rockettes. Nice touch was the introduction on stage of almost every American-based Honda racing champion from Gary Jones, who put Honda on the motocross map in the ’70s, right through to 1997 roadracing titlist Miguel Duhamel. The crowd took to its feet as one and cheered all 40 racers, a stirring moment. Next night, none other than the Temptations were brought in for after-dinner entertainment.

Not much in the way of new-model news, though. In typical Honda fashion, the CBR900RR gets about three singlespaced pages’ worth of improvements, but looks outwardly similar to previous Double-Rs-cool new yellow paint notwithstanding. Yet another variation on the V-Twin cruiser theme is the streamlined Aero, looking for all the world like a Shadow 1100 that’s been left in the wind tunnel overnight. Again, elegant but not exactly earth-shattering. And thanks to some silly intramural shoving match between Honda’s various overseas subsidiaries, there was only a vague video tease of the upcoming VFR800 Interceptor-we’d have to wait a week until its unveiling at the Paris Show for photos and hard info.

Later, as I walked through display halls full of Hondas both old and new, past partitions chock-a-block with memorabilia and old “You Meet the Nicest People on a Honda” ad slicks, I came across a solitary whitewashed wall. It contained a few faded photographs and served as backdrop to a simple square pedestal that held a beautiful lily among polished river rocks. On its front the words, “Soichiro Honda 1906-1991.”

Hard to believe it’s been six years since Mr. Honda passed away. Harder yet to believe that it’s been almost 25 years since he stepped down as president of the company he founded in September of 1948.

The man who would go on to become one of the 20th century’s industrial giants was bom in an isolated farming village that didn’t even have electricity. The eldest son of a blacksmith, he was at best a lackadaisical student.

“I was hopeless,” Honda fessed up to biographer Sol Sanders in the 1975 book, Honda: The Man and his Machines. “I did not like reading and writing. I hated calligraphy and composition. I often skipped these classes, went up to a hill behind the school, and stretched out on my back and watched the sky.” Hardly an early indication of greatness for a man who would eventually hold more than 100 patents and be inducted as the first Japanese into Detroit’s Automotive Hall of Fame.

At age 15, Honda, enamored of engines, packed off to Tokyo to toil away for six years as a lowly apprentice in an auto-repair shop. In 1923, the Great Kanto Earthquake leveled much of the city, including the garage, and killed some 70,000 people. It was during this calamity that Honda discovered motorcycles-and the value of entrepreneurship.

“Whenever I had time, I went downtown on a motorcycle we had managed to salvage,” he remembered. “It had a sidecar and I carried passengers who paid me to get about the city. I made money; I needed it to buy rice. But mostly I enjoyed myself riding around Tokyo at what seemed breakneck speeds on a motorcycle.”

In 1928, Honda returned to his home region and opened a garage of his own in Hamamatsu. It prospered, and soon he had a workforce of 50 in several shops. Honda became known for his wild parties, fast cars and eccentric actions. Once, annoyed at tax laws, he rented a fire engine and waited in ambush for the offending officials to come out of their building, whereupon they were promptly doused.

Turns out Honda, in the time-honored American tradition, was also a hot-rodder, setting speed records in a soupedup flathead Ford. Much later, his company’s racebikes and cars would win countless national and world crowns, but a 100-mph crash while leading the 1936 All-Japan Speed Rally almost killed Honda, crushing the left half of his face and putting him out of action for 18 months. It was during this recovery that Honda decided to get out of the garage business and into manufacturing. Piston rings, to be exact, which came 14 years and a world war before his first motorcycle.

Only trouble? He wasn’t very good at it. Piston rings seemed like relatively simple things to make, but Honda knew very little about metallurgy. He knew nothing of silicon, an element that allows for uniform heat distribution. “I am shamefaced to admit that we not only had no knowledge of the application of silicon, but we didn’t even know we needed it!” Honda said. At age 31, Honda went back to school to learn about metals.

Next hurdle was quality control. Toyota placed an order for 50,000 piston rings, but when 50 were pulled at random for inspection, only three were within specification. Another hard lesson learned.

“Looking back on my work, I feel that I have made nothing but mistakes, a series of failures, a series of regrets,” a self-effacing Honda said after retirement. “But I also am proud of an accomplishment: Although I made one mistake after another, I never made the same mistake, and I always tried my hardest and succeeded in improving my efforts.”

He elaborated on that theme in a graduation speech to the class of ’74 at Michigan Technological University: “Many people dream and hope for success. To me, success can be achieved only through repeated failure and introspection. In fact, success represents 1 percent of your work and results from the 99 percent that is called failure.”

Soichiro Honda, the man who made repeated failure a roaring success.