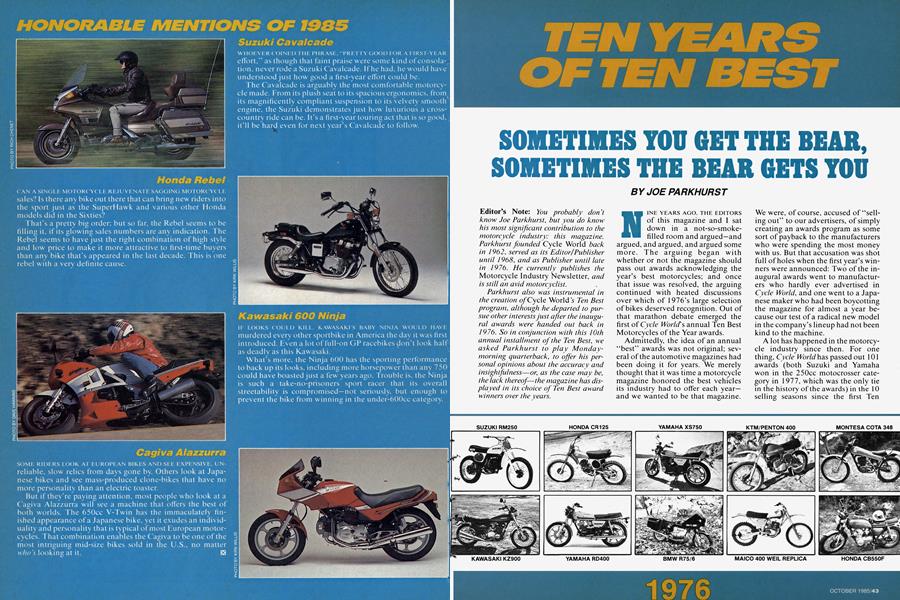

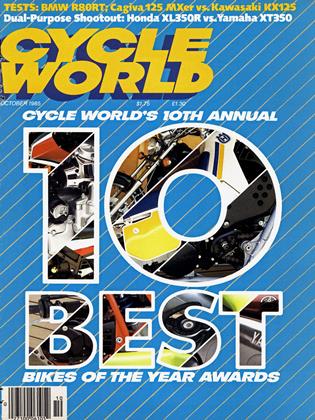

TEN YEARS OF TEN BEST

SOMETIMES YOU GET THE BEAR, SOMETIMES THE BEAR GETS YOU

JOE PARKHURST

Editor’s Note: You probably don't know Joe Parkhurst, but you do know his most significant contribution to the motorcycle industry: this magazine. Parkhurst founded Cycle World back in 1962, served as its Editor/Publisher until 1968, and as Publisher until late in 1976. He currently publishes the Motorcycle Industry Newsletter, and is still an avid motorcyclist.

Parkhurst also was instrumental in the creation ofC ycle Worlds Ten Best program, although he departed to pursue other interests just after the inaugural awards were handed out back in 1976. So in conjunction with this 10th annual installment of the Ten Best, we asked Parkhurst to play Mondaymorning quarterback, to offer his personal opinions about the accuracy and insightfulness—or, as the case may be, the lack thereof—the magazine has displayed in its choice of Ten Best award winners over the years.

NINE YEARS AGO, THE EDITORS of this magazine and I sat down in a not-so-smokefilled room and argued—and argued, and argued, and argued some more. The arguing began with whether or not the magazine should pass out awards acknowledging the year’s best motorcycles; and once that issue was resolved, the arguing continued with heated discussions over which of 1976’s large selection of bikes deserved recognition. Out of that marathon debate emerged the first of Cycle WorlcTs annual Ten Best Motorcycles of the Year awards.

Admittedly, the idea of an annual “best” awards was not original; several of the automotive magazines had been doing it for years. We merely thought that it was time a motorcycle magazine honored the best vehicles its industry had to offer each year— and we wanted to be that magazine.

We were, of course, accused of “selling out” to our advertisers, of simply creating an awards program as some sort of payback to the manufacturers who were spending the most money with us. But that accusation was shot full of holes when the first year’s winners were announced: Two of the inaugural awards went to manufacturers who hardly ever advertised in Cycle World, and one went to a Japanese maker who had been boycotting the magazine for almost a year because our test of a radical new model in the company’s lineup had not been kind to the machine.

A lot has happened in the motorcycle industry since then. For one thing, Cycle World has passed out 101 awards (both Suzuki and Yamaha won in the 250cc motocrosser category in 1977, which was the only tie in the history of the awards) in the 10 selling seasons since the first Ten Best. But in many ways, things haven’t changed much at all. In 1976, Cycle World talked about how far bikes had come over the years, how engine and suspension technologies were advancing with astonishing speed; yet today, on the 10th anniversary of the Ten Best awards, this magazine and most others are still talking about the same kinds of amazing advancements.

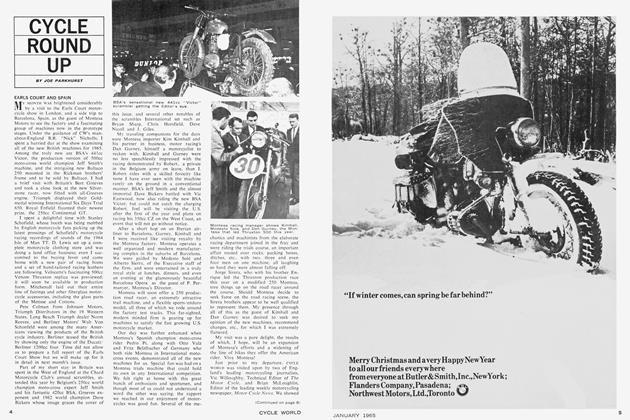

1976

1977

Despite those similarities, though, 1976 was an altogether different era in motorcycling. The sheer number of models available back then made choosing the IO best bikes extremely difficult, especially considering that it was our first time around. And as has been the case with practically every year’s collection of award winners, we hit a few homeruns that first year, and we had our share of strikeouts. Our 1976 Ten Best, for example, included a trials bike: the Montesa Cota 348. But as history will attest, the trials boom that most magazines—including this one—had been predicting for years never materialized. Strike Three.

On the brighter side, Cycle World named Suzuki’s RM250 the best 250cc motocrosser of 1976. We didn’t know it then, but the RM250 was one of the precursors of Japanese domination of motocross. So that choice definitely was a four-bagger. And for much the same reasons, so was our selection of Honda’s CR 125 as the best 125cc motocrosser of ’76. The two other dirt bikes that made the list that year weren’t such hall-offame candidates: The Penton 400 Six-Days was voted the best enduro bike even though it had a for-expertsonly power output; and the Maico Adolf Weil Replica won the best Open-class motocrosser award despite its questionable reliability and extremely high cost.

On the street side, the vote for 1976’s best 900-to-l000cc roadster went to Kawasaki’s KZ900. Two months later, the 900 was made obsolete by the KZ1000; but that didn’t matter, because both bikes, which were direct descendants of the famous Z-1, ranked among the best and most important motorcycles of our time. We weren’t so astute in our choice of Yamaha’s three-cylinder XS750 as the best 750 roadster; it later grew to an 850 and hung around for about five years, but never again came close to making the Ten Best.

In the years preceding our awards, it was generally accepted that either BMWs or Harley-Davidsons were unequalled as touring machines. And our vote for the best touring bike of 1976 went to BMW’s R75/6—not a bad choice, considering that it could stand side-by-side with a 1985 Boxer and lose little by comparison. But back then, we never imagined that the trend in touring would shift toward the enormous and complex rigs of today, nor that in 10 years, touring machines would be priced in the $8000-to-$ 10,000 range.

1978

1979

We also seemed to be something less than visionaries when we voted for Yamaha’s RD400 two-stroke Twin as the best 350-to-400cc roadster, claiming that the bike had reached perfection. The federal government's concerns with air pollution—and the American rider’s growing preference for four-stroke street machiner-y—had already put twostroke streetbikes on the endangeredspecies list. We were aware of this, but gave the RD400 the award anyway for one compelling reason: It was the best motorcycle in its class, regardless of engine type.

As the years passed, the Ten Best awards often reflected various trends that developed as the motorcycle industry continually reshaped itself. One example is Honda’s GL1000 Gold Wing. The big GL got no award that first year, even though it was revolutionary in design and enjoyed moderate sales success. But the bike became the legend it is today largely through the efforts of many small but enthusiastic manufacturers of accessories. In the late Seventies, Honda simply supplied an excellent basic machine, and the aftermarket finished the project by allowing the GL to be transformed into a uniquely American touring bike. It wasn’t until 1980 that Honda would capitalize on what the aftermarket had begun and introduce the Interstate. One year later, Honda would outdo itself with the indomitable Aspencade. The sad part of this success story is that most of those makers of fairings, saddlebags, touring trunks, stereos, cruise controls and other touring doo-dads have never fully recovered.

In this same period, Honda also introduced several other innovative machines that would earn spots in the Ten Best—some deservedly, some not-so-deservedly. One of the questionable award winners was Honda’s CX500, chosen as the best middleweight roadster of 1978. It was radical, liquid-cooled and automotive-inspired in its mechanical design, with V-Twin cylinders positioned transversely á la Moto Guzzi. The CX500 was quiet, efficient, simple to work on, had shaft drive—and was painfully slow and deadly dull to ride. Later on, Honda dressed up the CX in a stunning plastic cocoon and turbocharged the engine, but it still wasn't what the riding public was looking for. After its marketing failure as a turbo, the CX joined the ranks of the ignominious and hasn’t been seen since.

Earning an honorable mention in 1978 was another engineering tour de force from Honda: the CBX. Powered by an awesome-sounding and equally awesome-looking 1047cc Six, the CBX was billed as the Superbike to end all Superbikes, but that dream never became reality. Meager sales of the CBX prompted Honda to restyle the bike as a sporttouring model in 1980, but that approach also failed. Today the CBX is but a collector’s item.

1980

1981

Despite those early Ten Best faux pas, however, Cycle World entered the Eighties with its awards program a well-respected part of the motorcycle industry, as well as an important part of the magazine. But, as usual, the 1980 list had its hits and misses. One absolute bulls-eye was Kawasaki’s KZ550, a lightweight but exceptionally powerful street rocket. The 550 Kawasaki marked the start of a new era of high-performance small-bores that would leave lasting impressions on all who rode them. The biggest miss of the year was the Can-Am MX-6 250cc motocrosser. For some inexplicable reason, Cycle Worlds test Can-Am was an impressive performer, but the staff later learned that production units were proving less than competitive.

Another 1980 award winner was neither a hit nor a miss, but merely an unremarkable motorcycle. The editors said that Honda’s 400cc Hawk earned the distinction of being the best machine in its class as much “by default as through excellence.” At that time, the Hawk had taken the class award three years in a row. But this wasn’t because Honda was the only company making a 400cc streetbike; it was, according to the editors, simply that the other machines all had more flaws.

Until this point, no single manufacturer had ever dominated the awards. But that ended in 198 l when Suzuki took six of the 10 classes. All three of the motocrossers were RM Suzukis, and 1981 was t-he second year for the GSllOO as top Superbike; before that, the GS1000 had held the honor. In fact, between the GS 1000, the GS 1100 and the Katana 1000, Suzuki would hold a grip on the Superbike class for six years.

Of those six winners, the choice of the Katana 1000 in 1982 was the most controversial. The Katana was a perfect example of beauty truly being in the eye of the beholder. Although the bike was disarmingly fast, it also was brutally suspended and punishing to ride, and was really more of a styling exercise than a performance trend-setter. But by then, the staff of Cycle World had come to accept the fact that they weren’t always going to be right in their Ten Best choices.

In 1983, Honda, not Suzuki, won the lion’s share of awards. The 750 Interceptor certainly accounted for much of the glory, but Honda also had the best motocrossers, the best dual-purpose bike and the best enduro bike. But perhaps the biggest upset that year was what Honda didn't win: Yamaha’s Venture Royale stole the best touring bike award away from the Honda Gold Wing.

1982

1983

Yamaha’s other 1983 victory was the 550 Vision. When Cycle World named it the best 451-to-650cc streetbike, even the biggies at Yamaha were surprised, for they thought they had built a dud. As it turned out, they had, but at least it was a wellrounded dud powered by an excellent V-Twin engine. But due to its futureshock styling and lack of clear purpose, the Vision also had an embossed invitation to obscurity, which it validated before the year was out. Once again, Cycle World discovered that you can’t be right all the time.

Cruisers didn’t take their place in the awards until last year. Chopperstyled motorcycles—either the real thing or Japanese-built clones—traditionally were unloved by magazine editors; but by 1984, these kinds of machines had become such an integral part of American motorcycling that they could no longer be ignored. So the Best Cruiser category replaced the ever-dwindling Under-500cc class, and Harley-Davidson’s Disc Glide became the first cruiser to win in the Ten Best awards.

Last year also had its share of controversy, with Kawasaki’s Ninja not only displacing Suzuki in the Superbike category, but also edging Yamaha’s much-heralded FJ1100. Though not as good an all-around streetbike as the FJ, the Ninja was commended by Cycle World for being the most uncompromised, most single-purpose, most fun superbike ever to come out of Japan.

So as you can see, the first 10 installments of Cycle World's Ten Best awards have had their ups and downs. To be sure, some of the choices over the years have been dead-wrong; but that’s not suprising, considering that the editors have had to choose from as many as 300 different models each year. Which means that to come up with those 101 Ten Best winners since 1976, they’ve had to cull through 3000 bikes.

Perhaps more important is the overall track record of the Ten Best awards. If you isolate the small percentage of unfortunate choices, you find that the rest of the selections fall into two basic categories: motorcycles that were undisputedly the best bikes in their respective categories, and the rest that were at least arguably the best. And those selections had to be made each year before sales success could officially crown a motorcycle a winner, or before service records could demonstrate that it was anything but dead-reliable.

Sure, it’s a tough job; but then, no one really has to do it. But someone should. And Cycle World does. ES

1984

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

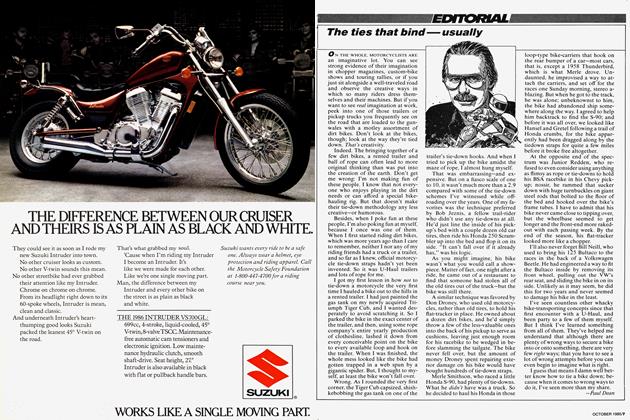

EditorialThe Ties That Bind Usually

October 1985 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeFighting Back

October 1985 By Steve Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1985 -

Roundup

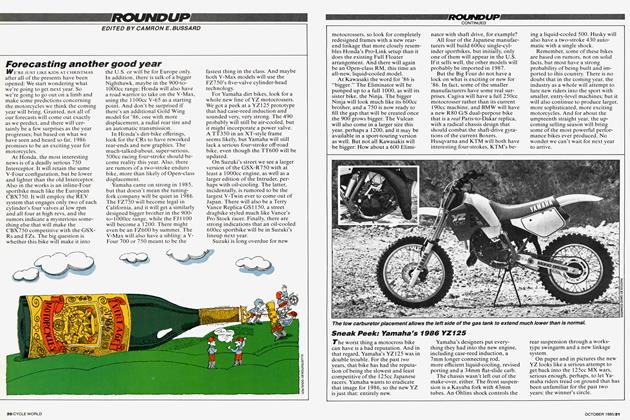

RoundupForecasting Another Good Year

October 1985 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

October 1985 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

October 1985 By Alan Cathcart