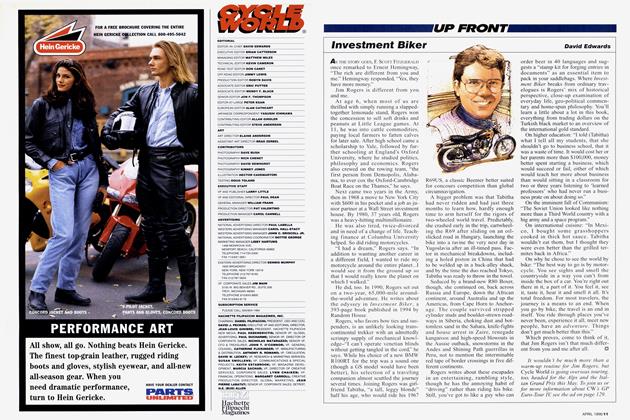

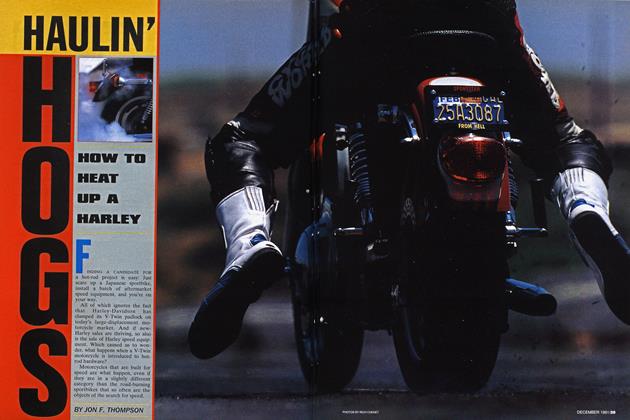

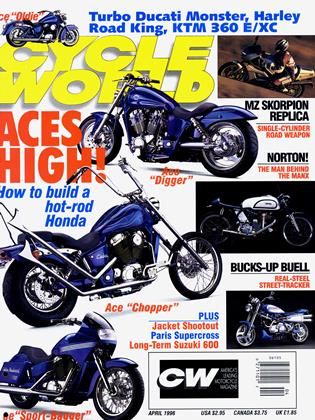

BOUTIQUE BUELL

A REAL-STEEL A HARLEY STREET-TRACKER

STEVE ANDERSON

DURING THE RENAISSANCE, THE newly wealthy merchant class, competing for status and prestige, commissioned paintings of themselves and their families, and thus supported a flowering of the visual arts that now fills museums. Several hundred years later, something similar is going on, but it's not happening with oil paintings-instead these new objets d'art are powered by Haney-Davidson.

If you don’t believe the analogy, we offer a solid bit of proof: this Buell XR, a motorcycle unlike any other, one that gathers crowds wherever it’s parked. It, too, is someday destined for a museum.

Its story begins with David Weinstein, a successful tax lawyer-surely the current equivalent of a Medici merchant prince— with his own firm in a prestigious location in L.A.’s Century City. Weinstein was new to motorcycling a few years ago; his first bike was an extensively customized Springer Softail. But after riding it for three years, he found that he was less and less comfortable with the black-leather image that was locked into the Softail’s genes, and that he was becoming a good enough rider to look for something a little more sporty. But not too sporty: “I just couldn’t see myself on something with Japanese laydown styling,” he says.

Enter Damian Gregory. Tall and ponytailed, Gregory could pass for the cold-eyed, too-clever-for-the-cops drug dealer Gregg Allman played in the movie Rush. And when he tells you the story about turning a routine pull-over into an impromptu brake test for the policeman chasing him, resulting in: 1) his trailer hitch being firmly implanted into the radiator of the police car; 2) the bad-guy officer drawing on him; 3) Gregory diving for the bushes as bullets whiz overhead; and 4) being rescued by the good-guy local sheriff, you start to think first impressions might carry some weight.

But there’s substance behind the attitude. In the early Eighties, Gregory worked for an engineering firm. He says, “I never intended to do this stuff. But I had someone put a gas tank on my XR1000, a four-and-a-half gallon one for Battle of the Twins racing, and it came adrift when I went to hang off in the first comer. I told him I could do better myself, and he said, ‘Yeah?’ So I did.” Work on his own BoTT Harley led to an offer to go to work for Bill Bartels’ Harley shop, helping convert a batch of XR750 dirt-trackers to street use. Soon enough, Gregory was running the roadrace department at Bartels’ and doing all the R&D. Later, he opened his own shop, Twin Sport (310/670-6423), where he did the engine and some detail work on Weinstein’s old Softail.

So it was natural the two should talk about Weinstein’s next bike. They discussed the merits of a streetable XR750, but dismissed that-too much vibration and far too maintenance-intensive. “Ride an XR750 for a weekend, and you’ll be working on it for a week,” warns Gregory. He suggested a Buell instead. But Weinstein didn’t like the roadracer look or riding position. He asked, “Can’t you make a Buell look like an XR750?” That simple question launched the project.

In May, 1994, Gregory started by buying a Buell RR1200 that had been gathering dust in a corner of Bartels’, a lightweight RR that had been built specially for the dealership’s roadracing effort. Trucking it back to his shop, Gregory recounts, “I took all the bodywork off and shot it. I took the photos to Kinkos and made some worksheets, then started making overlays.”

Very little of the original Buell would survive. Gregory stripped the frame of tabs and subframe, finger-molded the joints and began moving parts around. The battery migrated to its current spot low and in front of the engine, hiding behind a chin fairing Gregory made from scratch. That left room for equal-length exhaust headers to loop around to the left side of the bike and feed high-mounted, shallowly tapered megaphones, just like an XR. Gregory fabricated a new subframe and molded an XR-lookalike seat. Matching the minimal dimensions of an XR fuel tank would have been impossible given the Buell’s wide spaceframe, so Gregory carved a styrofoam plug that echoed the XR tank appearance (if not its scale) and shipped it to fabricator Jack Hagemann, who had once made the tanks for Kenny Roberts’ works Yamahas. Hagemann expertly translated Gregory’s styrofoam shape into hand-formed aluminum-all for a sum that would come close to paying for a new 883 Sportster.

And that was just the start. Gregory would work full-time on the Buell for almost half a year, putting more than 600 hours into the project. The detailing didn’t, couldn’t stop. Explains Gregory, “Everything is scaled like an XR on steroids. Three-quarter-inch handlebars looked like little weenies, and even 1-inch bars did, so I used l!4-inch tubing and made my own bars, stepping them down to 1-inch for the controls. I even made the instrument housings bigger—spinning them from sheet-to be in scale. This way, the upside-down fork doesn’t look so big. The bike looks like a 750 at a distance, but when you get close, something’s wrong. When people see the bike, they want to touch the handlebars, check and see if their eyes are fooling them.” But perhaps the most telling details are the front tumsignals, little polished bits of amber jewelry set into the tubes that act as fairing mounts on other Buells. “Someone asked me at a bike show,” says Weinstein, “where Damian got the front signals. I told him, ‘He made them.’ And the guy said, ‘Yeah, I know, but what did he start with? He must have cut them down from something.’ And I told him that he made them-that he machined the reflectors, and made molds, and cast the lens, and tinted them-that he made the tumsignals!” The signals are intensely bright, projecting a sharp, amber, 4-foot circle on a wall 10 feet from the bike.

The upside-down fork and rear shock are WP units, similar to those used on current Buells. They were set-up by suspension expert Stig Pettersson, who had earlier developed Öhlins shocks to work on BoTT Buells-one of the first shocks that worked well with Buell’s unusual pullshock suspension design. Similarly, the 1200 engine for this bike drew heavily on Gregory’s prior experience with Bartels’ racebikes. It’s a balanced and blueprinted 1200, one that Gregory describes as “happy at 7500 rpm.” A three-stage DPD oil pump with a 5:1 ratio of scavenge-topressure flow turns the Sportster powerplant into one with a truly dry sump, and helps maintain a power-boosting negative crankcase pressure at all times. Gregory personally ported the heads and modified the combustion chambers, and fitted an out-of-production Mikuni 40mm flat-slide, “because it gives better throttle response” than the current 42mm carb Mikuni offers for Harleys. After an initial try with Redline racing cams, Gregory slipped in a set of Andrews N4s-a mild grind-to give the bike the streetability Weinstein wanted. With 15 discs in the SuperTrapp mufflers, Gregory estimates that the engine puts out 80 to 85 horsepower at the rear wheel.

In any case, now that it’s in Weinstein’s hands, the attorney is thrilled. “It’s unbelievable,” he says, “especially coming from a traditional Harley. There’s almost no vibration. And the handling: I haven’t gotten close to 50 percent of its limit. I’m always trying to lean over further, accelerate a little bit harder-it’s going to take years for me to learn how to get close to its limits. The bike only weighs 430 pounds; it’s monstrously fast.”

And for now, we’ll have to take his word for that. After sinking enough money into the Buell XR to make a reasonable down payment on beach-front property, or buy a handful of close friends their own Buell Sis, Weinstein only shares his ride with Gregory.

The patron is more than happy with his real-steel artist. Weinstein explains, “The criteria were to make it look like a dirt-track bike, to make it fun to ride, and to make it something I could park and leave and not worry about.”

He pauses, and you can almost hear his smile over the phone: “We hit two out of three.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue