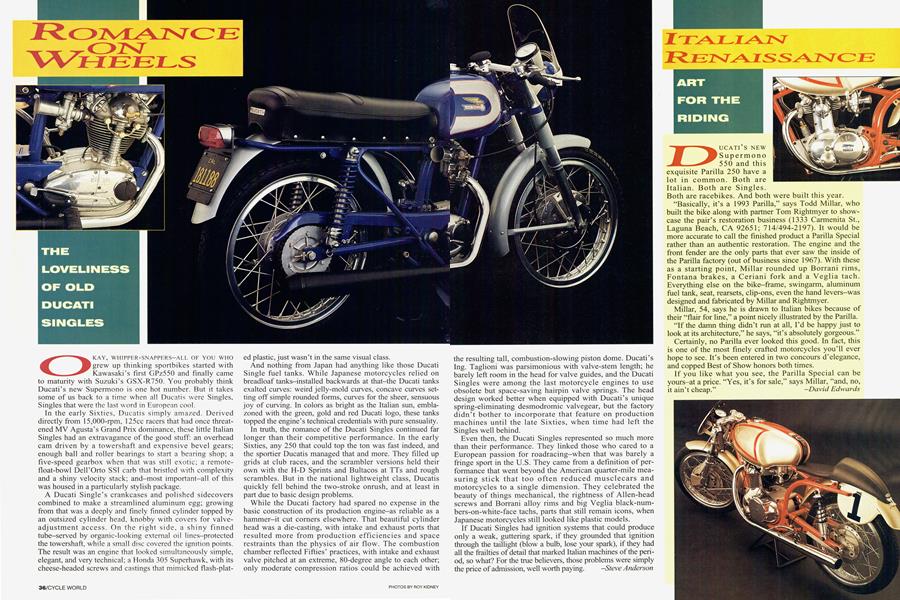

ROMANCE ON WHEELS

THE LOVELINESS OF OLD DUCATI SINGLES

OKAY, WHIPPER-SNAPPERS-ALL OF YOU WHO grew up thinking sportbikes started with Kawasaki's first GPz55O and finally came to maturity with Suzuki's GSX-R750. You probably think Ducati's new Supermono is one hot number. But it takes some of us back to a time when all Ducatis were Singles, Singles that were the last word in European cool.

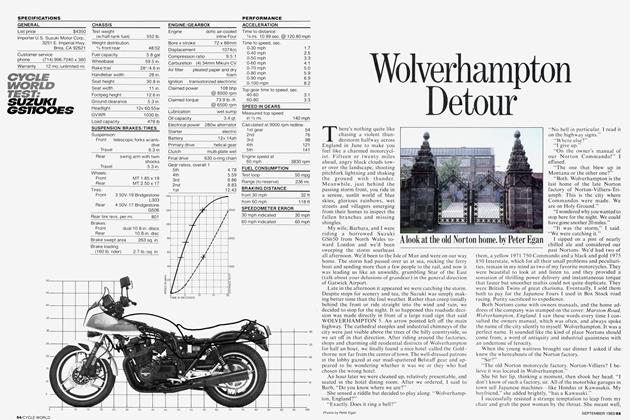

In the early Sixties, Ducatis simply amazed. Derived directly from 15,000-rpm, 125cc racers that had once threatened MV Agusta’s Grand Prix dominance, these little Italian Singles had an extravagance of the good stuff: an overhead cam driven by a towershaft and expensive bevel gears; enough ball and roller bearings to start a bearing shop; a five-speed gearbox when that was still exotic; a remotefloat-bowl Dell’Orto SSI carb that bristled with complexity and a shiny velocity stack; and-most important-all of this was housed in a particularly stylish package.

A Ducati Single’s crankcases and polished sidecovers combined to make a streamlined aluminum egg; growing from that was a deeply and finely finned cylinder topped by an outsized cylinder head, knobby with covers for valveadjustment access. On the right side, a shiny finned tube-served by organic-looking external oil lines-protected the towershaft, while a small disc covered the ignition points. The result was an engine that looked simultaneously simple, elegant, and very technical; a Honda 305 Superhawk, with its cheese-headed screws and castings that mimicked flash-plated plastic, just wasn’t in the same visual class.

And nothing from Japan had anything like those Ducati Single fuel tanks. While Japanese motorcycles relied on breadloaf tanks-installed backwards at that-the Ducati tanks exalted curves: weird jelly-mold curves, concave curves setting off simple rounded forms, curves for the sheer, sensuous joy of curving. In colors as bright as the Italian sun, emblazoned with the green, gold and red Ducati logo, these tanks topped the engine’s technical credentials with pure sensuality.

In truth, the romance of the Ducati Singles continued far longer than their competitive performance. In the early Sixties, any 250 that could top the ton was fast indeed, and the sportier Ducatis managed that and more. They filled up grids at club races, and the scrambler versions held their own with the H-D Sprints and Bultacos at TTs and rough scrambles. But in the national lightweight class, Ducatis quickly fell behind the two-stroke onrush, and at least in part due to basic design problems.

While the Ducati factory had spared no expense in the basic construction of its production engine-as reliable as a hammer-it cut corners elsewhere. That beautiful cylinder head was a die-casting, with intake and exhaust ports that resulted more from production efficiencies and space restraints than the physics of air flow. The combustion chamber reflected Fifties’ practices, with intake and exhaust valve pitched at an extreme, 80-degree angle to each other; only moderate compression ratios could be achieved with the resulting tall, combustion-slowing piston dome. Ducati’s Ing. Taglioni was parsimonious with valve-stem length; he barely left room in the head for valve guides, and the Ducati Singles were among the last motorcycle engines to use obsolete but space-saving hairpin valve springs. The head design worked better when equipped with Ducati’s unique spring-eliminating desmodromic valvegear, but the factory didn’t bother to incorporate that feature on production machines until the late Sixties, when time had left the Singles well behind.

Even then, the Ducati Singles represented so much more than their performance. They linked those who cared to a European passion for roadracing-when that was barely a fringe sport in the U.S. They came from a definition of performance that went beyond the American quarter-mile measuring stick that too often reduced musclecars and motorcycles to a single dimension. They celebrated the beauty of things mechanical, the rightness of Allen-head screws and Borrani alloy rims and big Veglia black-numbers-on-white-face tachs, parts that still remain icons, when Japanese motorcycles still looked like plastic models.

If Ducati Singles had ignition systems that could produce only a weak, guttering spark, if they grounded that ignition through the taillight (blow a bulb, lose your spark), if they had all the frailties of detail that marked Italian machines of the period, so what? For the true believers, those problems were simply the price of admission, well worth paying.

Steve Anderson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

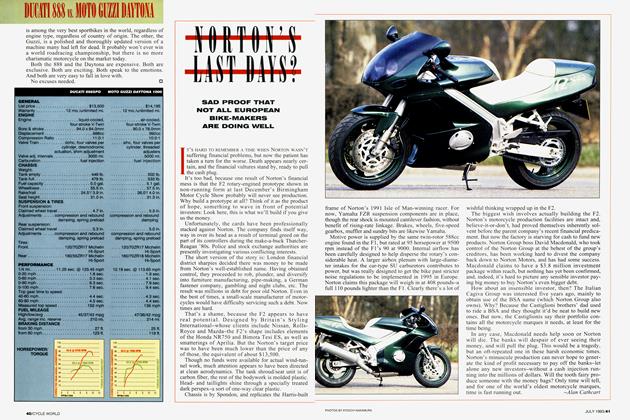

Up FrontTomb of the Unknown Harleys

September 1993 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsDo Loud Pipes Save Lives?

September 1993 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCVicious Cycles

September 1993 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1993 -

Roundup

RoundupBmw Sings A Song of Singles

September 1993 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupPick A Pair of Yamaha 600s

September 1993