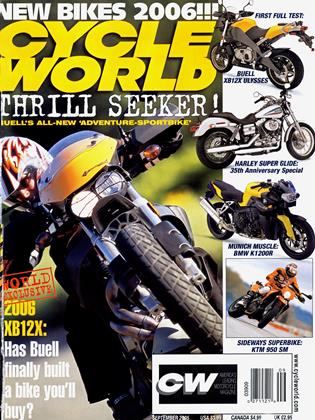

THE NEW BUELL

Long way from a Mukwanago garage

Perhaps the most impressive thing Erik Buell has built isn’t a motorcycle, but an organization. A visit to the Buell Motorcycle Company reveals a small outfit that has grown rapidly in the last decade, and is filled with exceptionally bright and enthusiastic staffers.

Buell Motorcycle occupies two modern and efficient 40,000square-foot industrial buildings on the edge of the small town of East Troy, Wisconsin, just off the freeway and about 30 miles from Milwaukee. Either building would hold in a small corner the original garage Buell started in 20 years ago, but they’re also a world away from parent company Harley-Davidson. A meeting with the young engineering staff explains why.

Harley product design, of course, is driven by Willie G. Davidson and Louie Netz of its styling department. That’s not Buell. Tony Stefanelli, the engineer in charge of the XB platform explains, “What Erik has done is to instill a friendliness for new ideas. If it didn’t work out the first time, for God’s sake do it differently—find out what science tells you to do, then do it.”

This is a relatively different approach to motorcycle chassis design, which at most companies is strongly driven by traditional solutions. It’s led Buell to radically different designs that Erik and crew defend with passion. Take the controversial under-engine muffler, for example. “It’s four times more expensive than the simple round can you see on many sportbikes,” says Buell. But the elaborate baffling and powervalve give the XBs more power, and the location “is in absolutely the right place from a mass centralization standpoint.” To emphasize the low yaw inertia of the Buell design, Erik has you hold competitors’ muffler systems in hand as if you’re at the vertical axis of the bike and then try to move them quickly. The clumsiness of the others compared with the Buell system quickly makes his point.

Similarly, he gives comparative weights of front brake, tire and wheel assemblies. The XB’s design, with its featherweight wheel and inside-out brake, is a third again lighter than competitive machines. And contrary to what you might read in certain motorcycle magazines given to wild theorizing, the rotor/wheel assembly has substantially less rotary inertia than conventional sportbike setups, even with the larger-diameter disc.

Abe Ashkenazi, head of Buell’s Analytical Engineering Department, describes product test procedures similarly: “Erik has instilled this spirit here at Buell that you have to look at fundamentals. When we do new things, we have to do it the right way.” Burned by problems with the old tube-frame bikes, Ashkenazi and John Bunne of Test Engineering have gone out of their way to develop the best testing science around, using statistical methods, brutal field evaluations and accelerated lab tests to qualify new products. The results show up in the initial quality of new products, with the idea that the customer shouldn’t be the beta tester for a new motorcycle.

But perhaps the most impressive thing about the young Buell engineering staff (12 design engineers, two analytical, three powertrain) is that they almost uniformly ride motorcycles-and quickly at that. There aren’t many motorcycle companies that when you go on a ride with the engineering wonks, you have to ride quickly to keep up. But perhaps that’s explained in part by the competitive spirit that clearly blazes at Buell. Listen to Stefanelli, who only came to work for Buell when his racecar ride for the next season fell through: “In these two buildings are seven world or national champions, everything from motorcycling to snowmobiling to gokarts. That tells you a lot about who we are.”

Steve Anderson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontHauiin'

September 2005 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsIn Praise of Cop Bikes

September 2005 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCMarket Value

September 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

September 2005 -

Roundup

RoundupFuture Road-Burner Revealed?

September 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupVictory's Jackpot

September 2005 By Calvin Kim