Trial by Fire

RACE WATCH

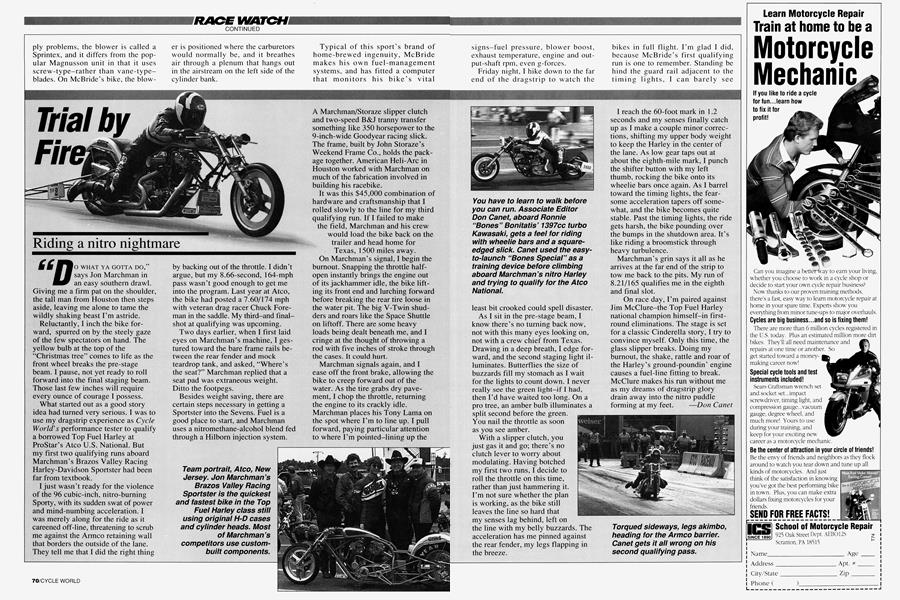

Riding a nitro nightmare

"DO WHAT YA GOTTA DO," says Jon Marchman in an easy southern drawl. Giving me a firm pat on the shoulder, the tall man from Houston then steps aside, leaving me alone to tame the wildly shaking beast I’m astride.

Reluctantly, I inch the bike forward, spurred on by the steely gaze of the few spectators on hand. The yellow bulb at the top of the “Christmas tree” comes to life as the front wheel breaks the pre-stage beam. I pause, not yet ready to roll forward into the final staging beam. Those last few inches will require every ounce of courage I possess.

What started out as a good story idea had turned very serious. I was to use my dragstrip experience as Cycle World’s performance tester to qualify a borrowed Top Fuel Harley at ProStar’s Ateo U.S. National. But my first two qualifying runs aboard Marchman’s Brazos Valley Racing Harley-Davidson Sportster had been far from textbook.

I just wasn’t ready for the violence of the 96 cubic-inch, nitro-burning Sporty, with its sudden swat of power and mind-numbing acceleration. I was merely along for the ride as it careened off-line, threatening to scrub me against the Armco retaining wall that borders the outside of the lane. They tell me that I did the right thing by backing out of the throttle. I didn’t argue, but my 8.66-second, 164-mph pass wasn’t good enough to get me into the program. Last year at Ateo, the bike had posted a 7.60/174 mph with veteran drag racer Chuck Foreman in the saddle. My third-and finalshot at qualifying was upcoming.

Two days earlier, when I first laid eyes on Marchman’s machine, I gestured toward the bare frame rails between the rear fender and mock teardrop tank, and asked, “Where’s the seat?” Marchman replied that a seat pad was extraneous weight. Ditto the footpegs.

Besides weight saving, there are certain steps necessary in getting a Sportster into the Sevens. Fuel is a good place to start, and Marchman uses a nitromethane-alcohol blend fed through a Hilborn injection system. A Marchman/Storaze slipper clutch and two-speed B&J tranny transfer something like 350 horsepower to the 9-inch-wide Goodyear racing slick. The frame, built by John Storaze’s Weekend Frame Co., holds the package together. American Heli-Arc in Houston worked with Marchman on much of the fabrication involved in building his racebike.

It was this $45,000 combination of hardware and craftsmanship that I rolled slowly to the line for my third qualifying run. If I failed to make the field, Marchman and his crew would load the bike back on the trailer and head home for Texas, 1500 miles away.

On Marchman’s signal, I begin the burnout. Snapping the throttle halfopen instantly brings the engine out of its jackhammer idle, the bike lifting its front end and lurching forward before breaking the rear tire loose in the water pit. The big V-Twin shudders and roars like the Space Shuttle on liftoff. There are some heavy loads being dealt beneath me, and I cringe at the thought of throwing a rod with five inches of stroke through the cases. It could hurt.

Marchman signals again, and I ease off the front brake, allowing the bike to creep forward out of the water. As the tire grabs dry pavement, 1 chop the throttle, returning the engine to its crackly idle. Marchman places his Tony Lama on the spot where I’m to line up. I pull forward, paying particular attention to where I’m pointed-lining up the least bit crooked could spell disaster.

As I sit in the pre-stage beam, I know there’s no turning back now, not with this many eyes looking on, not with a crew chief from Texas. Drawing in a deep breath, I edge forward, and the second staging light illuminates. Butterflies the size of buzzards fill my stomach as I wait for the lights to count down. I never really see the green light—if I had, then I’d have waited too long. On a pro tree, an amber bulb illuminates a split second before the green. You nail the throttle as soon as you see amber.

With a slipper clutch, you just gas it and go; there’s no clutch lever to worry about modulating. Having botched my first two runs, I decide to roll the throttle on this time, rather than just hammering it. I’m not sure whether the plan is working, as the bike still leaves the line so hard that my senses lag behind, left on the line with my belly buzzards. The acceleration has me pinned against the rear fender, my legs flapping in the breeze.

I reach the 60-foot mark in 1.2 seconds and my senses finally catch up as I make a couple minor corrections, shifting my upper body weight to keep the Harley in the center of the lane. As low gear taps out at about the eighth-mile mark, I punch the shifter button with my left thumb, rocking the bike onto its wheelie bars once again. As I barrel toward the timing lights, the fearsome acceleration tapers off somewhat, and the bike becomes quite stable. Past the timing lights, the ride gets harsh, the bike pounding over the bumps in the shutdown area. It’s like riding a broomstick through heavy turbulence.

Marchman’s grin says it all as he arrives at the far end of the strip to tow me back to the pits. My run of 8.21/165 qualifies me in the eighth and final slot.

On race day, I’m paired against Jim McClure-the Top Fuel Harley national champion himself-in firstround eliminations. The stage is set for a classic Cinderella story, 1 try to convince myself. Only this time, the glass slipper breaks. Doing my burnout, the shake, rattle and roar of the Harley’s ground-poundin’ engine causes a fuel-line fitting to break. McClure makes his run without me as my dreams of dragstrip glory drain away into the nitro puddle forming at my feet.

Don Canet

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontSex Lessons

FEBRUARY 1992 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsBoots And Saddles

FEBRUARY 1992 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCThe Cannon Connection

FEBRUARY 1992 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

FEBRUARY 1992 -

Roundup

RoundupAll-New Bmw Twin: Tradition Takes A Turn

FEBRUARY 1992 By Jon F. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki's Little Engine That Thinks Big

FEBRUARY 1992 By Yasushi Ichikawa