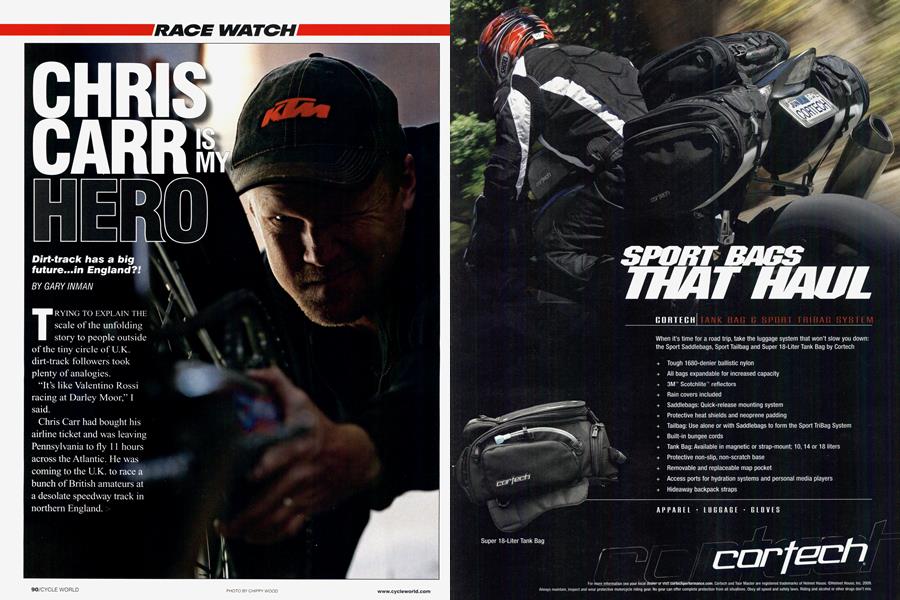

CHRIS CARR IS MY HERO

RACE WATCH

Dirt-track has a big future...in England?!

GARY INMAN

TRYING TO EXPLAIN THE scale of the unfolding story to people outside of the tiny circle of U.K. dirt-track followers took plenty of analogies.

“It’s like Valentino Rossi racing at Darley Moor,” I said.

Chris Carr had bought his airline ticket and was leaving Pennsylvania to fly 11 hours across the Atlantic. He was coming to the U.K. to race a bunch of British amateurs at a desolate speedway track in northern England.

And the Rossi analogy isn’t stretching the truth. Carr is in the running to be greatest dirt-tracker of all time. His seven AMA Grand National Championships put him in every pundit’s top-five. He won the two biggest races on the dirt-track calendar in 2008: the Springfield and Indy Miles. Being the wrong side of 40 might mean he’s unlikely to add to his seven titles, but that doesn’t mean he isn’t still a massive threat, a massive name and a massive draw in the U.S. When it comes to paydays, well, the British flat-track scene had little to give back.

What was Carr thinking?

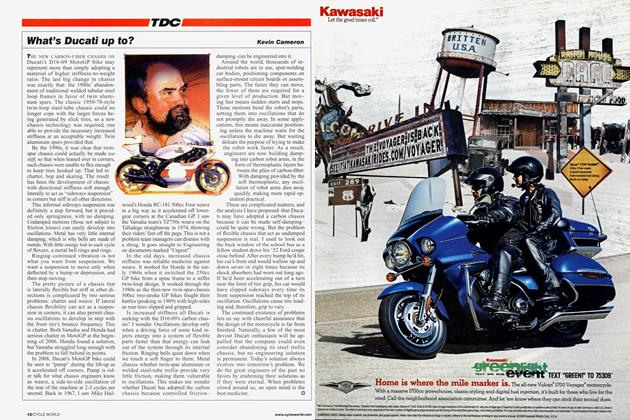

Saturday morning. A thin, blue, midOctober sky is struggling to brighten Eddie Wright Raceway in Scunthorpe.

A Bahamian sun, hula girls and a fistful of ecstasy would have a job livening up this place. The home of the Scunthorpe Scorpions Premier League speedway team is unremittingly bleak. Past the steelworks, through the morass of gaudy, credit-crunched car dealers and Baghdad-style driveways sits the track. Ex-works panel vans and Euro-size RVs crowd the paddock. A slight figure bulked up with layers of hoodies and canvas jackets walks toward the open, corrugated steel-roofed sheds that act as the pit buildings. Chris Carr really is here. And today, he’s going to tutor a race school, sharing some of his experience with two dozen U.K. racers, me included.

In the fantastically named Ozchem Billabong, a pre-fab bar and clubhouse, Carr is introduced to his pupils. Spontaneous applause erupts.

“I just want to start by thanking you all,” begins the confident Carr, “for racing dirt-track and for taking the sport somewhere new. You are the pioneers. Hopefully, in years to come, people will look back and acknowledge you as the racers who helped dirt-track grow in Europe.”

As intros go, this one is solid gold. Some men will later admit they were almost moved to tears. And Carr wasn’t just throwing out a line. He’s left behind his wife and family to come here, and he did it because he loves his sport. He’s the pros’ pro, yet he’s here for little more than expenses.

“I’ve been watching the progress of the Short Track U.K. championships and Mefo Cup in Europe, and I have a lot of admiration for the progress that’s been made here,” he continues. “I’ve always been about making the sport bigger and better, not what I get out of it. I think if the whole sport grows, I’ll earn more out of it eventually, anyway.”

Carr tells us what we’re going to do and gives us some hard truths. “I’ve looked at some photos of you guys racing, and there are some strange body positions going on. So today we’re mainly going to work on what I call body English.”

Jeez, we’re not even sitting on our bikes correctly.

The morning consists of doing donuts on Chinese minibikes, then riding the same bikes around the tiny kids’ oval, sometimes with one hand on top of the gas tank. Light bulbs are flashing over the heads of virtually every pupil’s head. We haven’t gone more than 20 mph, but we’re learning some fundamentals for the first time.

I look around and realize we’re the marsupials of the flat-track world.

We’re cut off from the source, so we’ve developed our own style. Squint and we could pass for normal mammals, but no one told us we shouldn’t carry our kids around in a pouch.

“When I see you guys and the tracks you ride, I see that you’ve developed a speedway style of riding. I’m teaching you how to ride like a flat-tracker,” Carr tells a silent audience. “You are all sliding and gassing it way too hard. When we race, our area of danger is about this much,” he says, pointing to a six-foot space at the entry of the comer. “Your area of danger is three-quarters of the track!”

At the end of the day, Carr receives 24 heartfelt thanks and as many firm handshakes. He accepts every one like it’s his first. >

Then the biggest name in dirt-track spends the night before the race in the spare room at the home of Peter Boast, a top racer and father of U.K. Short Track. “It’s rural, it’s quiet, but I live in rural Pennsylvania, so it’s not strange,” Carr says. “Five-star hotels are okay if someone else is paying, but this is no different than going to houses of flat-trackers in America. We do that all the time.”

During his visit, Carr has become quite a fixture in the local pub, where he tries cider and Guinness, answers questions from locals about his 350mph land-speed-record run and, according to his host, “gets quite merry.”

Sunday morning and the pits are buzzing. New awnings have been brought in to give the paddock area a more professional look. Carr has inspired the biggest entry of the year. The series is run on a shoestring. Boast and his partner, Jackie, like so many true enthusiasts, put in time and effort that few could match. And the only reward is that Boast gets to compete in a sport he loves. A handful of extra entries

makes a big difference. And this season has been tough. Terrible weather has kept spectators away, so many races have run at a loss, the money leaching directly out of Boast's bank account. But it looks like this month will be kind to the flat-trackers.

When Carr arrived at Manchester Airport, he looked like a Tarantino hit man, striding through with a rifle case. Inside were the tools of his trade: modified KTM fork and shock. That’s all he really needed to make a KTM 450 competitive.

“We took delivery of the bike on Wednesday,” he says. “We put the fork and shock on the bike. Pete got me a 19-inch front wheel, we put a Maxxis dirt-track front tire on it, a 19-inch rear wheel, then filled it up with gas. The fork is from a 2007 KTM, shortened by 4 inches. The shock is a WP drop-out shock; it’s got a bit of give at the bottom, and it’s been shortened about 1.5 inches. Other than that, I haven’t made a chassis adjustment all the time I’ve been here.”

Riders are checking tire pressures, chatting with Carr, filling tanks, everyone is smiling. The shout goes up for the riders’ meeting. The procedures and timetable are explained. Carr stands shoulder-to-shoulder with the amateurs. Finally, he’s introduced.

“I’ve had a great week, but that doesn’t mean I’m going to take it easy on you,” he says. >

We all laugh and lap it up. We’re here to be taught a lesson. We want to be humiliated. I’m sure there are some riders who think, who dream, that perhaps they can beat Chris Carr because he’s on a borrowed bike, on unfamiliar tracks. For the rest of us, we want our arses kicked by a master.

The next time Carr appears, he is in his Brain leathers. The American will race two bikes today, the mildly modified KTM and, in the Thunderbike class, a pure short-tracker-an old, twin-shock, Ron Wood-framed Rotax.

It belongs to Colin Batchford and turns up in the back of a decommissioned ambulance. Batchford normally races it, but he broke his wrist on it earlier in the season. The irony of his mode of transport isn’t lost on anyone.

In his first heat, Carr isn’t into the first corner first but he rides round the outside, somehow takes four bikelengths out of everyone and leads until a redflag incident. He’s braking a yard deeper than the very best in Europe, getting the bike stopped and turned in a ridiculously short space of time. The riders on the fence are asking, “How is he doing that?” At the restart, he wins again.

In his next qualifying heat, Carr takes out the Wood-Rotax. This time, I line up with him on my own Wood-Rotax. He could have been talking directly to me when he was assessing the riding he saw yesterday. “I don’t see a lot of bikes limiting riders, but I see a lot of riders limiting bikes,” he’d said. I’ve known all along that the right rider could win on my bike. I can’t, though.

Still, I’m into the first corner second behind Steve Coles on his modified Honda Hawk, and I come out third behind Carr. After a lap or so, Carr pulls to the outside of the track with a problem. I keep chasing Coles. With one bend to go on the last lap, Carr comes around the outside of me. I finish third in the 12-man heat. Carr is second.

A British rider on a cobbled-together roadbike has beaten him. I’m happy to have been beaten by Carr. If he’d have chugged over the line with a sick bike, it would’ve been a hollow victory. As it> is, it’s noble defeat. Coles is applauded as he returns to the pits.

“The safety switch was askew,” Carr explains as he watches the next heat. “The bike is good. I grew up on that bike. The first 500 I raced was a Ron Wood Rotax.”

Then he notices a DTX-style Honda enduro. “It’s funny to see a race bike with a brakelight. I get a giggle out of it.”

Marsupials. Every one of us.

Carr races more heats on the Rotax, winning them all, but is being kept honest by the best European racers. Then he wins his semi in the Short Track class. Conclusions have rarely been more foregone.

Between now and the Short Track final, he will have a battle with Boast, on his Suzuki SV650 in a one-off frame, and John Lee, riding a homebuilt, bigbore Honda Transalp in a KTM MX chassis, in the Thunderbike final.

Then it’s the event for which everyone has been waiting. The 12 finalists have their bikes pushed out onto the track. The best qualifier is allowed to pick his position on the front row. Carr picks gate three. He lines up with Boast and Marco Belli-both in with a chance of winning the 2009 title-plus a bunch of pro speedway aces, top-class supermoto riders and racers from other disciplines attracted by the low cost and camaraderie of the series.

After a warm-up lap, everyone hunkers over their wide bars and stares at the starting tapes fluttering in the cold wind.

‘Tve never raced with speedway tapes,” Carr had said earlier.

Perhaps it’s the tapes, but he doesn’t get off the line the quickest. Still, within half a lap, he’s in the lead. Boast tucks in behind, but he can’t quite match the pace. Behind him, Belli is riding with a shoulder dislocated the day before.

“He epitomizes flat-track racing,” Carr says of the Italian. “I saw the wreck and I saw the pain. It’s admirable.”

With a few laps of the 12-lap final remaining, Carr is into the backmarkers, riders who are no mugs by our standards. This is a very fast final. He gently picks his way through, not needing, or wanting, to barge. It’s a master class in racing minimalism. Last year, Brandon Robinson, a young American at the beginning of what will be a big career, came to the U.K. to race and he > blew everyone away with his audacity. Carr’s performance is as dominant but completely different.

He takes the flag, pulls a huge wheelie then literally takes the flag to do a lap of honor with the checkers fluttering in one hand. Boast came second, Belli third, enough to win the championship.

“The pressure I was under was the pressure I put on myself to win,” says Carr as he packs his gearbag. “It’s inner pride. Flag, lights or tapes, when it goes up, I’m racing.”

Carr came here, rightly billed, as a champion. If he hadn’t won, he’d have felt like he was short-changing everyone involved. He was honest, respectful, not patronizing and gave a gift of a Chris Carr beer-can cooler to every racer.

Later, at a very low-key end-of-season awards ceremony in the Ozchem Billabong, Carr cements his position in the hearts of the U.K. dirt-trackers. Back in his hoodie, jacket and baseball cap, the dirt-track maestro is surrounded by new friends with dirty faces and wild, sweaty hair. He has a pint of lager in each hand.

“I’ve met people during this week that I’ll be friends with for a long time,” he says. Then, perhaps not wanting to sound too soft, he adds, “The bar’s open!”

The relief is painted on Boast’s face. He personally invested a lot to bring Carr over, and if it had rained, it would’ve all been lost. But it didn’t. “When Chris Carr raced here, he made people’s dream come true,” Boast says.

He’s not exaggerating. How often does something like this happen? How about never? U