The Tennant Creek Theory

AT LARGE

Steven L. Thompson

ACCORDING TO THE BOOK EXPLORING Australia, the town of Tennant Creek in the Northern Territory might well have been founded when a beer wagon broke down on the Stuart Track and the drivers stayed to drink the cargo. Since I was there with my own broken-down wagon (a Range Rover which had lost its windshield to a now-deceased vulture), this story sounded reasonable. Australia's like that, a place where anything's possible.

While my erstwhile traveling companions and I waited in the shade, the sunburnt Aussie who ran the “smash repairs” shop wrestled with replacing the windshield. As he worked, I wandered the shop’s yard. What about the handful of newish Toyota and Nissan trucks strewn around? 1 asked. Although they were only a couple of model years old, they were ruined, blasted hulks.

He grimaced and glanced at the nearest wreck. They were abandoned, he said. By Aboriginals who had been “given” the things by the government, then driven them until they broke and just left them. “Given?” I asked. “Bloody right,” he grated. In his opinion, because the Native Australians had not been forced to work to buy the trucks, they treated them as children treat their toys; they use them up, then simply toss them away.

If you measure every human value by the yardstick of racial prejudice, you’d probably have assumed the guy was a white bigot. You’d be wrong. He didn't blame the Aboriginals. He blamed the government. “It’s like rental cars,” he said. “If you haven’t worked for it, and you don't have to take care of it, you won't, will you?”

This was one of those little vignettes of insight that lodge in your mind like popcorn on a molar. Any arent knows the awful truth of this; ids have to be taught the Golden Rule, and Responsibility, and Sharing, and all that stuff that glues society together. It doesn’t come naturally to homo sap. Not like greed, lust and pride, say.

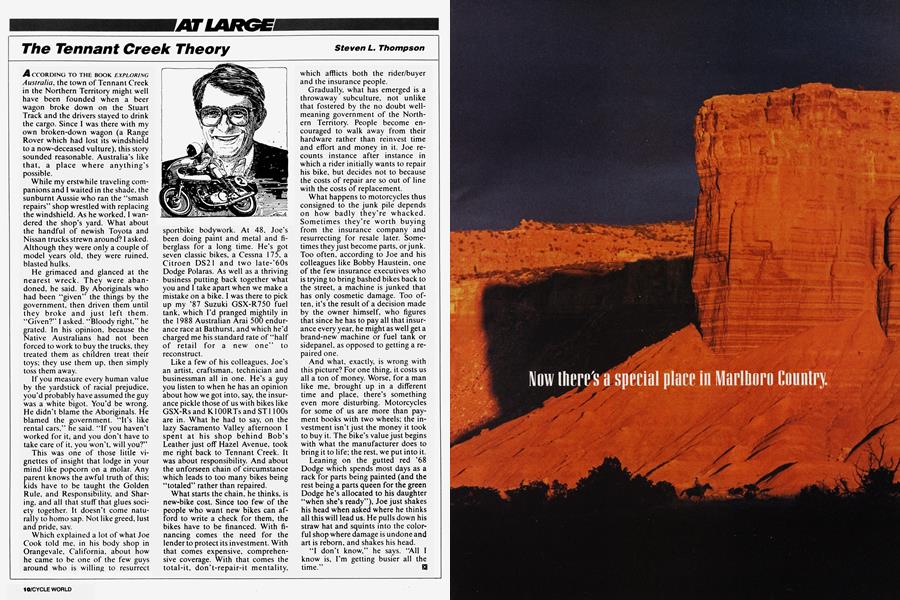

Which explained a lot of what Joe Cook told me, in his body shop in Orangevale, California, about how he came to be one of the few guys around who is willing to resurrect sportbike bodywork. At 48, Joe's been doing paint and metal and fiberglass for a long time. He’s got seven classic bikes, a Cessna 175, a Citroen DS21 and two late-’60s Dodge Polaras. As well as a thriving business putting back together what you and I take apart when we make a mistake on a bike. I was there to pick up my ’87 Suzuki GSX-R750 fuel tank, which I’d pranged mightily in the 1988 Australian Arai 500 endurance race at Bathurst, and which he'd charged me his standard rate of “half of retail for a new one'' to reconstruct.

Like a few of his colleagues, Joe’s an artist, craftsman, technician and businessman all in one. He’s a guy you listen to when he has an opinion about how we got into, say, the insurance pickle those of us with bikes like GSX-Rs and K1 OORTs and ST 1 100s are in. What he had to say, on the lazy Sacramento Valley afternoon I spent at his shop behind Bob’s Leather just off Hazel Avenue, took me right back to Tennant Creek. It was about responsibility. And about the unforseen chain of circumstance which leads to too many bikes being “totaled” rather than repaired.

What starts the chain, he thinks, is new-bike cost, Since too few of the people who want new bikes can afford to write a check for them, the bikes have to be financed. With financing comes the need for the lender to protect its investment. With that comes expensive, comprehensive coverage. With that comes the total-it, don't-repair-it mentality.

which afflicts both the rider/buyer and the insurance people.

Gradually, what has emerged is a throwaway subculture, not unlike that fostered by the no doubt wellmeaning government of the Northern Territory. People become encouraged to walk away from their hardware rather than reinvest time and effort and money in it. Joe recounts instance after instance in which a rider initially wants to repair his bike, but decides not to because the costs of repair are so out of line with the costs of replacement.

What happens to motorcycles thus consigned to the junk pile depends on how badly they’re whacked. Sometimes they’re worth buying from the insurance company and resurrecting for resale later. Sometimes they just become parts, or junk. Too often, according to Joe and his colleagues like Bobby Haustein, one of the few insurance executives who is trying to bring bashed bikes back to the street, a machine is junked that has only cosmetic damage. Too often, it’s the result of a decision made by the owner himself, who figures that since he has to pay all that insurance every year, he might as well get a brand-new machine or fuel tank or sidepanel, as opposed to getting a repaired one.

And what, exactly, is wrong with this picture? For one thing, it costs us all a ton of money. Worse, for a man like me, brought up in a different time and place, there’s something even more disturbing. Motorcycles for some of us are more than payment books with two wheels; the investment isn’t just the money it took to buy it. The bike’s value just begins with what the manufacturer does to bring it to life; the rest, we put into it.

Leaning on the gutted red ’68 Dodge which spends most days as a rack for parts being painted (and the rest being a parts queen for the green Dodge he’s allocated to his daughter “when she’s ready”), Joe just shakes his head when asked where he thinks all this will lead us. He pulls down his straw hat and squints into the colorful shop where damage is undone and art is reborn, and shakes his head.

“I don’t know.” he says. “All I know is. I’m getting busier all the time.” S