Life under a liter

AT LARGE

WELL, I TOOK THE LAD'S MONEY, BUT it wasn't the right thing to do. I know' that now, and I know it'll irk me as long as I ride. Not because I fleeced him—quite the opposite, he got a bargain—but because the motorcycle was so good.

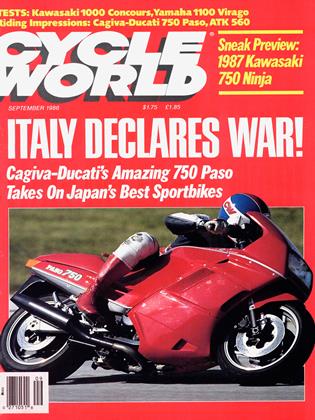

It was a 1984 Kawasaki GPz550. I bought it new in May of ’85 for $2832 and sold it for $1700, a year and 7700 miles later. In between, it won my heart and wowed me in a way that most of the bikes that come the way of a moto-magazine writer simply do not.

Technically, the 550 was to be my son's high-school graduation gift. The idea was that he'd ride the bike through the summer, then we'd sell it when he entered college in the fall. Swell plan, but it didn't take into account the performance, reliability and general winning ways of the 550. As it got used through the summer months—mostly by Andrew —I came more and more to appreciate the subtleties of the thing. I finally decided it was the ultimate development of the Understandable Motorcycle.

You may find that hard to believe. So would I, before I spent a year with the bike. It was a year of revelations. Such as: fuel consumption so good it seemed impossible, given the performance (about 55 mpg. I figure, for the year); performance so good it just flat seemed impossible, period; a fully adjustable, easy-to-tune suspension that let this sportbike ride like a touring rig over the choppy, slippery pavement so common in the middle Atlantic states, w hile ensuring stable, predictable lines through any and all corners, from full-lock hairpins to heart-in-mouth sweepers.

It commuted. It blitzed twisties. It toured, in one trip going 1600 miles from Washington. D.C., down the Blue Ridge Parkway to Charleston, South Carolina, and back along the Outer Banks—never missing a beat, never complaining about the load it carried, which consisted of fully jammed Eel ipse Saddlepacks, a Yoshimura Buddy Bag and a BagMan Tank Bag.

Total problems for the ownership period were confined to complaints about the seat, a tendency for the lefthand "clamp-on" handlebar to work slightly loose, and an annoying habit of the fuel tank to burp out a little fuel when full, slightly staining the metallic silver paint. I replaced the absurd stock mirrors—which only showed great views of the rider's shoulders—with Napoleon bar-ends. And it used up its stock Mag Mopus rear tire, which was replaced at 6000 miles with a Metzeier ME99.

Impatient for ultimates, this kind of performance seems to many of us not so impressive. Partly it's because the GPz550 is not unique, these days, in its willingness to give yeoman service for a pittance, and partly it's because the ultimates are so far out and so rapidly changing. But I never tired of riding that lithe, narrow bike, which reminded me, oddly, of the world's best Triumph Bonneville—a Bonnie that might have been, had the bovs in Meriden had the time and J money and commitment from their bosses to build the plants capable of building the bike. The GPz is, after all. still little more than an aircooled. steel-tube-framed motorbike, curiously old-fashioned in this era of Wonder Rockets From Mars.

I came to appreciate small things, such as the way the engineers arranged the information and systemsdiagnostic displays. Those displays impressed me with their thoroughness and "layering" of data. The big, round gauges at the lower center of your vision window told you what you needed most—speed and engine rpm (or voltage, at the push of a button)—while the warning-light panel, at the very bottom of your peripheral vision, used large, bright red, orange, green and blue lights to signal system status. The red warning light I especially liked, since it monitored the systems in the third array of displays, the liquid-crystal oil, fuel, battery and sidestand status. Any of those systems dropping out of normal parameters would fire the warning light and call your attention to the systemstatus LCD. which would be flashing the suspect item on and off. But the bonus was that none of the geegaws came at the expense of lightness or performance or caused needless complexity.

Reflecting on this, I realized one day that the GPz's performance and handling were so good—not "good for a streetbike," but just plain good— that the proud yellow Norton Production Racer that stood in restored splendor next to it wilted by comparsion. On a good day, that 748cc air-cooled Twin we had raced in England during 1972 could manage a mid-12-second quarter, and would top out, given the right longcourse gears, in the 1 30-mph range. But there was and is no comparison in handling; the GPz's sophisticated Uni-Trak and tunable fork would have allowed me to best the Norton’s times at any circuit from the TT Mountain Course to Brands Hatch. Realizing that was quite a shock, especially when I recall the slavish devotion of the emerging crop of Commando fanatics back in '72. and the almost disdainful attitude of the bulk of today's riders to the attainments of the GPz550.

I knew that this was the right comparison when I watched the young man gleefully ride his/my GPz out of my driveway, and recognized the same sinking feeling I'd felt back in 1972, when in a moment of utter foolishness, I’d sold the Commando P-Racer. People who worship OneLiter Wonder Rockets From Mars will not agree, but I think this sinking feeling means only one thing: Some day, that little GPz is going to be recognized as a Classic Bike. I just hope I can afford to buy it back then. What I have to hope for is that the same blindness that has made bikes like it so undervalued on today’s markets will prevail then. too.

It’s not much to hope for. but it’s all I’ve got. Because the GPz is gone. If not forgotten.— Steven L. Thompson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialDiscovering the Truth In Turn One

September 1986 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1986 -

Roundup

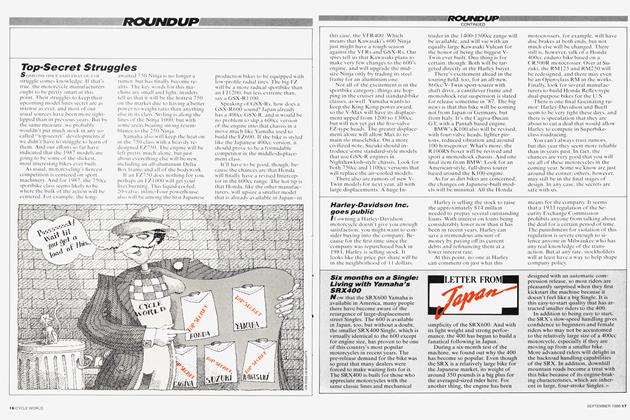

RoundupTop-Secret Struggles

September 1986 -

Roundup

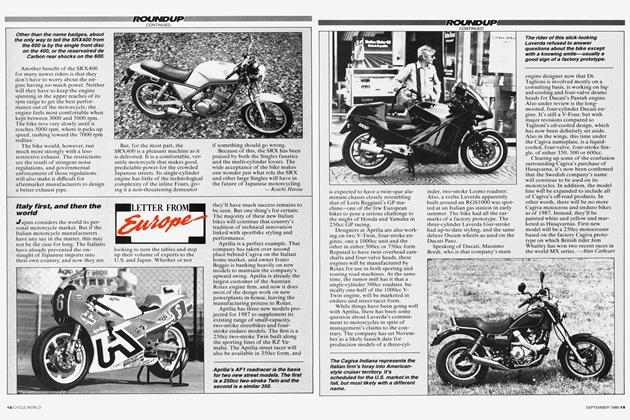

RoundupItaly First, And Then the World

September 1986 By Alan Cathcart -

Features

FeaturesMassimo Tamburini On Pasos And Paganini

September 1986 By Steve Anderson -

Features

FeaturesDr.Taglioni Designer of "Difficult Bicycles"

September 1986 By Steve Anderson