Discovering the truth in Turn One

EDITORIAL

OKAY. SO IT WASN'T THE MOST CONVEnient place for a revelation. But wide-eyed discoveries are like that: They just come to mind whenever the spirit moves them. That afternoon, on Yamaha's test track in Fukuroi, Japan, the spirit was working overtime.

It happened in Turn One, a long, lefthand. top-gear sweeper, with the throttle pegged wide-open and the hike heeled over far enough to have the centerstand hardy skimming the blacktop. I had been closing in on an other rider, one on a 600 Radian, as I recall, and thought I had the whole affair timed so I would slip past him on the inside as we both exited the turn. But just before the apex, he un expectedly hacked ofi the throttle for a split-second while I did not, and suddenly we were both trying to oc cup\ the same piece of track at the same time-a fine recipe for turning two perfectly good new Yamahas into salvage-yard stew.

More as an instinctive reaction than as a consciously act. I gave the handlebars a sharp tug, hoping to make the hike turn even harder to the left. As soon as I did that, what had been a light, intermittent scraping of the undercarriage sudden lv became a piercing graunch and a Fourth-OfJuly shower of sparks as the entire motorcycle yawed first in a counter clockwise direction, then clockwise, and then .

And then, iwI/l/ng. The hike sim ply regained its composure and con tinued around the turn, ahead of the Radian. No huge. hair-raising afterwobbles or wallows. No sliding tires or off-track excursions. Best of all. no hone-shattering. I 75-feet-per-second get-ofi. Just business as usual.

Such incidents are frequent occur rences on racetracks. Fukuroi was lu dicrous-and I would he hard-pressed to explain otherwise-it was the ab surdity of my actions that triggered the aforementioned revelation. Be cause immediately after my close call, somewhere on the short straight between Turn One and Turn 1 wo. it dawned on me that while riding a mammoth. Winnebago of a motorcy cle designed for more-or-less vertical sightseeing at rational speeds, I had just survived a racetrack incident that, not too many years ago. would have tested the mettle of even the finest sporting machines. And that, in turn, made me realize that motorcycles of all types and sizes had grown so amazingly competent over the past decade or so that testing them—which is what we motorcycle-magazine types do—had gotten to be damned hard.

That might seem like a contradiction, for a logical person would think that as motorcycles get better, the testing of them would get easier. But just the opposite is the case. Testing a motorcycle involves, among other things, finding its limits in all relevant areas of performance. And when the levels of performance dramatically and continually are raised, as the manufacturers have done over the past decade or so. those limits become ever-more-difficult to reach. Granted, new-and-improved bikes do make normal riding easier by steering more easily, turning more precisely, stopping more quickly and accelerating more effortlessly. But testing is almost the exact opposite of “normal” riding, and finding the dimensions of the performance envelope becomes more difficult every new-model year. More fun, usually, and safer, as well. But definitely harder.

Until that day at Fukuroi. though, I never really thought about all this, even though I've been involved in motorcycle-magazine test-riding for more than 1 3 years. But when I think back to when Í first began in this business. I recall that my fellow testers and I were able to find the performance limits of' just about any streetbike without ever making a tire print on a racetrack. A few hours of spirited charging on a good, twisty backroad invariably uncovered the strengths and weaknesses of even the best sport machines; and thanks to the low-tech suspensions, fiexy-flier frames and low-buck tires that were the trademarks of that era. the shortcomings of most other streetbikes were even easier to pinpoint, sometimes showing up when simply going around city street corners or turning into driveways.

These days, it’s a different story altogether. Tremendous advances in chassis design and tire technology allow today's worst-handling streetbikes to be better-behaved than most sport machines of 10 or 15 years ago—as my encounter on the Venture so graphically illustrated. And today's sport motorcycles, which are faster and better-handling than most of the sophisticated roadracing bikes of the early Seventies, are little more than pure race machines thinly disguised as streetbikes.

Consequently, when we need to know where the limits really are on most of today's motorcycles, we have little choice but to go to a racetrack; and once we get there, we generally have to ride so aggressively in search of those limits that we feel less like we're testing and more like we're auditioning for a factory roadrace team. Even at that, we usually have to take along some go-fast pro racer to help us locate those limits; and sometimes, even he has trouble finding them.

But look, don't feel sorry for us testers—or for me, at least; I love every minute I spend in search of the outer limits of performance. Why. I'm even looking forward to herding a big touring rig around a racetrack once again. But I will tell you this: Il I need to pass a 600 Radian, this time I’m going to give it a wide, wide berth. Paul Dean

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

At Large

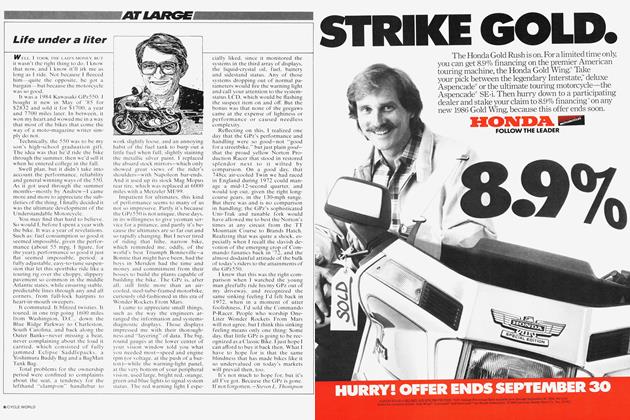

At LargeLife Under A Liter

September 1986 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1986 -

Roundup

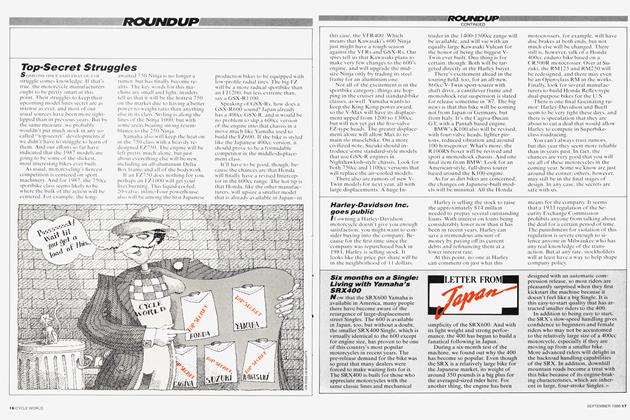

RoundupTop-Secret Struggles

September 1986 -

Roundup

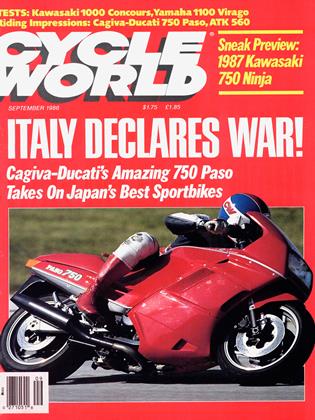

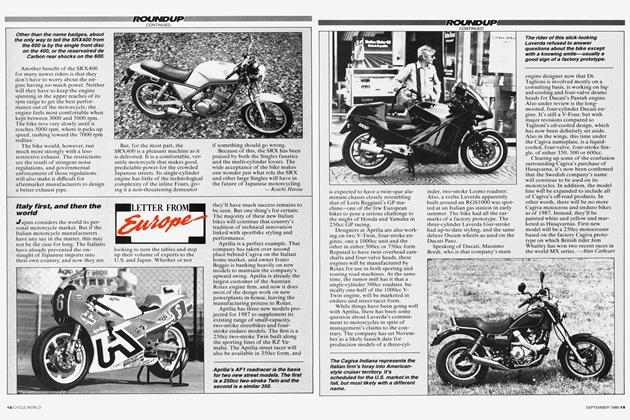

RoundupItaly First, And Then the World

September 1986 By Alan Cathcart -

Features

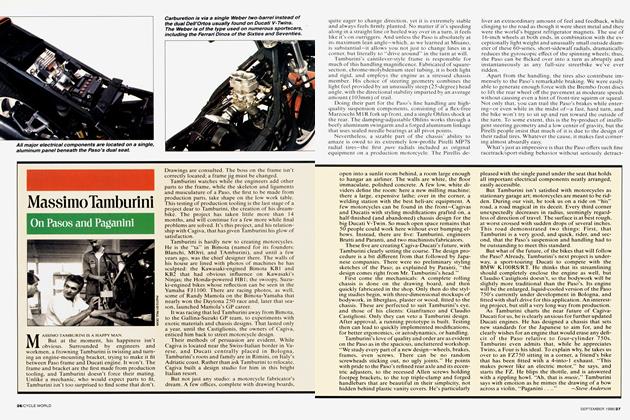

FeaturesMassimo Tamburini On Pasos And Paganini

September 1986 By Steve Anderson -

Features

FeaturesDr.Taglioni Designer of "Difficult Bicycles"

September 1986 By Steve Anderson