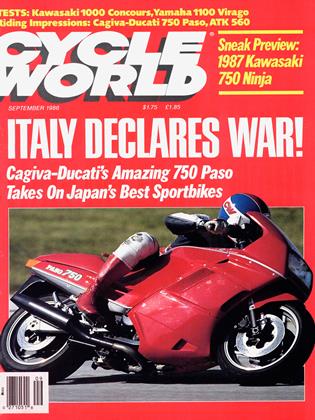

Massimo Tamburini On Pasos and Paganini

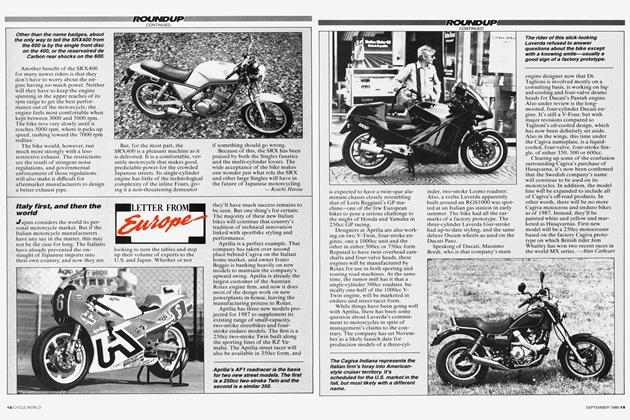

MASSIMO TAMBURINI IS A HAPPY MAN. But at the moment, his happiness isn't obvious. Surrounded by engineers and workmen, a frowning Tamburini is twisting and turning an engine-mounting bracket, trying to make it fit between Paso frame and Ducati engine. It won't. The frame and bracket are the first made from production tooling, and Tamburini doesn't force their mating. Unlike a mechanic, who would expect parts to fit, Tamburini isn't too surprised to find some that don't. Drawings are consulted. The boss on the frame isn’t correctly located; a frame jig must be changed.

Tamburini watches while the engineers add other parts to the frame, while the skeleton and ligaments and musculature of a Paso, the first to be made from production parts, take shape on the low work table. This testing of production tooling is the last stage of a project dear to Tamburini, the creation of his dreambike. The project has taken little more than 14 months, and will continue for a few more while final problems are solved. It’s this project, and his relationship with Cagiva, that has given Tamburini his glow of satisfaction.

Tamburini is hardly new to creating motorcycles. He is the “ta” in Bimota (named for its founders: Blanchi, MOrri, and TAmburini), and until a few years ago, was the chief designer there. The walls of his house are lined with photos of machines he has sculpted: the Kawasaki-engined Bimota KB1 and KB2 that had obvious influence on Kawasaki’s Ninjas; the Honda-powered HB1; the swoopy, Suzuki-engined bikes whose reflection can be seen in the Yamaha FJ1100. There are racing photos, as well, some of Randy Mamola on the Bimota-Yamaha that nearly won the Daytona 250 race and, later that season, launched Mamola’s GP career.

It was racing that led Tamburini away from Bimota, to the Gallina-Suzuki GP team, to experiments with exotic materials and chassis designs. That lasted only a year, until the Castiglionis, the owners of Cagiva, enticed him back to street motorcycle design.

Their methods of persuasion are evident. While Cagiva is located near the Swiss-Italian border in Varese, and Ducati centrally placed in Bologna, Tamburini’s roots and family are in Rimini, on Italy’s Adriatic coast. Rather than ask Tamburini to relocate, Cagiva built a design studio for him in this bright Italian resort.

But not just any studio: a motorcycle fabricator’s dream. A few offices, complete with drawing boards, open into a sunlit room behind, a room large enough to hangar an airliner. The walls are white, the floor immaculate, polished concrete. A few low, white dividers define the room: here a new milling machine; there a large, expensive lathe; over in the corner, a welding station with the best heli-arc equipment. A few motorcycles can be found in the front—Cagivas and Ducatis with styling modifications grafted on, a half-finished (and abandoned) chassis design for the big Ducati V-Twin. So much open space remains that 50 people could work here without ever bumping elbows. Instead, there are five: Tamburini, engineers Brutti and Paranti, and two machinists/fabricators.

These five are creating Cagiva-Ducati’s future, with Tamburini clearly setting the course. The design procedure is a bit different from that followed by Japanese companies. There were no preliminary styling sketches of the Paso; as explained by Paranti, “the design comes right from Mr. Tamburini’s head.”

First come the mechanicals: A complete rolling chassis is done on the drawing board, and then quickly fabricated in the shop. Only then do the styling studies begin, with three-dimensional mockups of bodywork, in fiberglass, plaster or wood, fitted to the chassis. These are perfected to suit Tamburini’s eye, and those of his clients: Gianfranco and Claudio Castiglioni. Only they can veto a Tamburini design. After approval, a running prototype is built. Testing then can lead to quickly implemented modifications, for better ergonomics, or aerodynamics, or handling.

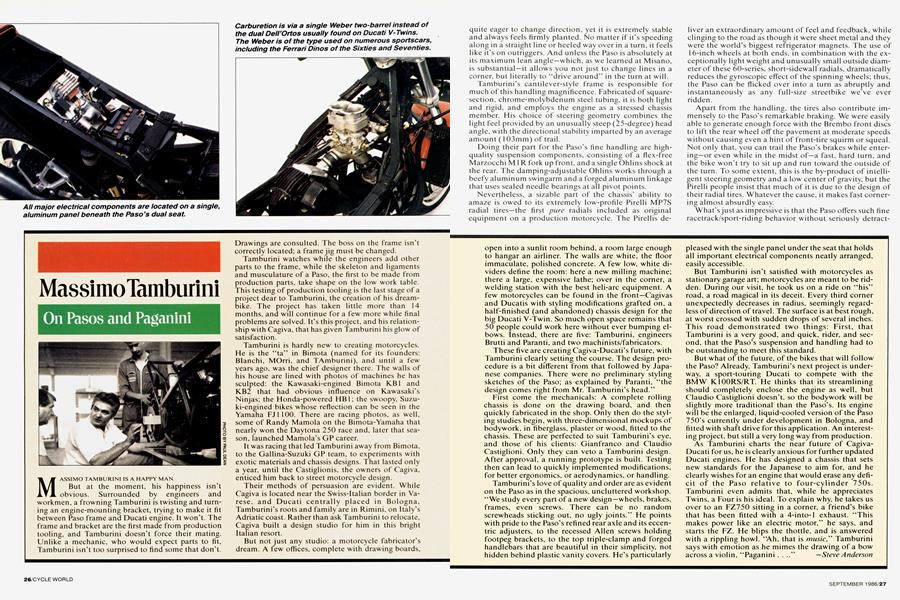

Tamburini’s love of quality and order are as evident on the Paso as in the spacious, uncluttered workshop. “We study every part of a new design—wheels, brakes, frames, even screws. There can be no random screwheads sticking out, no ugly joints.” He points with pride to the Paso’s refined rear axle and its eccentric adjusters, to the recessed Allen screws holding footpeg brackets, to the top triple-clamp and forged handlebars that are beautiful in their simplicity, not hidden behind plastic vanity covers. He’s particularly

pleased with the single panel under the seat that holds all important electrical components neatly arranged, easily accessible.

But Tamburini isn’t satisfied with motorcycles as stationary garage art; motorcycles are meant to be ridden. During our visit, he took us on a ride on “his” road, a road magical in its deceit. Every third corner unexpectedly decreases in radius, seemingly regardless of direction of travel. The surface is at best rough, at worst crossed with sudden drops of several inches. This road demonstrated two things: First, that Tamburini is a very good, and quick, rider, and second, that the Paso’s suspension and handling had to be outstanding to meet this standard.

But what of the future, of the bikes that will follow the Paso? Already, Tamburini’s next project is underway, a sport-touring Ducati to compete with the BMW K100RS/RT. He thinks that its streamlining should completely enclose the engine as well, but Claudio Castiglioni doesn’t, so the bodywork will be slightly more traditional than the Paso’s. Its engine will be the enlarged, liquid-cooled version of the Paso 750’s currently under development in Bologna, and fitted with shaft drive for this application. An interesting project, but still a very long way from production. As Tamburini charts the near future of Cagiva-

Ducati for us, he is clearly anxious for further updated Ducati engines. He has designed a chassis that sets new standards for the Japanese to aim for, and he clearly wishes for an engine that would erase any deficit of the Paso relative to four-cylinder 750s. Tamburini even admits that, while he appreciates Twins, a Four is his ideal. To explain why, he takes us over to an FZ750 sitting in a corner, a friend’s bike that has been fitted with a 4-into-l exhaust. “This makes power like an electric motor,” he says, and starts the FZ. He blips the thottle, and is answered with a rippling howl. “Ah, that is music," Tamburini says with emotion as he mimes the drawing of a bow across a violin, “Paganini . . ..” —Steve Anderson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialDiscovering the Truth In Turn One

September 1986 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeLife Under A Liter

September 1986 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1986 -

Roundup

RoundupTop-Secret Struggles

September 1986 -

Roundup

RoundupItaly First, And Then the World

September 1986 By Alan Cathcart -

Features

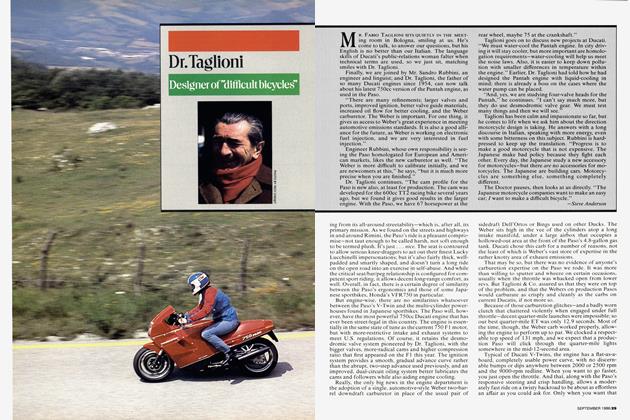

FeaturesDr.Taglioni Designer of "Difficult Bicycles"

September 1986 By Steve Anderson