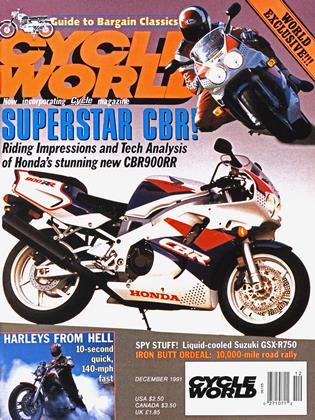

SUPER CBR

HONDA SHEDS SOME NEW LIGHT ON OPEN-CLASS

PAUL DEAN

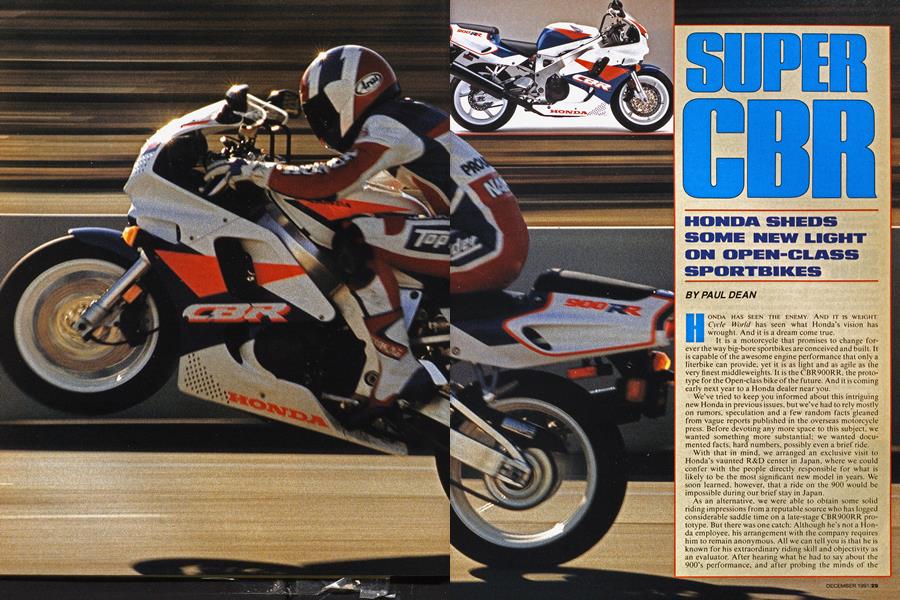

HONDA HAS SEEN THE ENEMY. AND IT IS WEIGHT. Cycle World has seen what Honda’s vision has wrought. And it is a dream come true.

It is a motorcycle that promises to change forever the way big-bore sportbikes are conceived and built. It is capable of the awesome engine performance that only a literbike can provide, yet it is as light and as agile as the very finest middleweights. It is the CBR900RR, the prototype for the Open-class bike of the future. And it is coming early next year to a Honda dealer near you.

We’ve tried to keep you informed about this intriguing new Honda in previous issues, but we’ve had to rely mostly on rumors, speculation and a few random facts gleaned from vague reports published in the overseas motorcycle press. Before devoting any more space to this subject, we wanted something more substantial: we wanted documented facts, hard numbers, possibly even a brief ride.

With that in mind, we arranged an exclusive visit to Honda's vaunted R&D center in Japan, where we could confer with the people directly responsible for what is likely to be the most significant new model in years. We soon learned, however, that a ride on the 900 would be impossible during our brief stay in Japan.

As an alternative, we were able to obtain some solid riding impressions from a reputable source who has logged considerable saddle time on a late-stage CBR900RR prototype. But there was one catch: Although he's not a Honda employee, his arrangement with the company requires to remain anonymous. All we can tell you is that he is known for his extraordinary riding skill and objectivity as an evaluator. After hearing what he had to say about the 900’s performance, and after probing the minds of the people who conceived and created it, we reached an inescapable conclusion: The CBR900RR is going to rewrite everyone's definition of Open-class performance.

At a claimed 408 pounds and w ith a wheelbase of just 55.1 inches, the 900 is a mere w isp of a big-bore sportbike, matching even the lightest 600-class machines in weight and overall size. And although the 120-horsepower output of its 893ce engine falls I 5 or 20 ponies short of what the hottest Open-class iron currently pumps out. simple arithmetic tells you what's reu/lv important: that each horsepower must propel just 3.4 pounds, giving the 900 a power-to-w eight ratio w hich equals or exceeds that of any production streetbike of any size.

Everything the test rider told us confirmed what the numbers suggested. As he put it, “It's hard to describe just how' capable this motorcycle really is. But try to imagine a bike that physically feels no bigger than a Honda CBR600F2. that accelerates much like a Kawasaki ZX-II, and that has the chassis composure of a Honda RC30. If your imagination can conceive of anything so far-fetched, you'll end up with a pretty good idea of what the 900 is like to ride.''

Wow! Those are unbelievably high marks, considering that the bikes he chose for comparison reside at the very top of their respective classes. It makes you wonder what radical new technology had to be employed to produce such an astounding motorcycle. Has Honda made some breakthroughs in engine design, chassis configuration or materials application? Is the CBR900RR a techno-mechanical tour lie force whose stunning performance has demanded abnormally high levels of complexity and manufacturing costs?

Our visit to Honda R&D provided a clear answer: absolutely. positively not. In fact, the most amazing aspect of the CBR900RR may be that its designers achieved such phenomenal performance without resorting to exotic means. This, folks, is about as straightforward asa modern motorcycle gets, incorporating little that isn't in regular use on other machines.

The engine, for example—an oversquare, dohc. liquidcooled, 16-valve inline-Four—is contemporary but certainly not exceptional, either in design or in power output. And the chassis is built around an aluminum perimeter frame fitted with single-shock rear suspension and a double-sided swingarm, all of which are fairly conventional. You can, admittedly, spot some unusual bits and pieces poking out here and there, but they play only minor roles in this bike’s potentially award-winning performance.

Really, the only major difference between this motorcycle and other Open-class streetbikes is in weight. If Honda's claimed dry-weight figure of 408 pounds is reasonably accurate, the 900 will roll out of the showroom between 100 and 140 pounds lighter than any other bike in its class. Not even Suzuki's revolutionary GSX-R750 of 1985 chopped such massive amounts of weight from the class norm: and producing that landmark Suzuki required the introduction of new technologies to the world of streetbikes. But Honda favored more practical methods in its development of this ultra-light Open bike, allowing the CBR900RR to achieve its feathery state without exotic materials and radical designs.

It's a well-known fact that weight is the factor most detrimental to overall performance. The more a motorcycle weighs, the more reluctantlt is to accelerate, to stop, to change direction or to lean into a corner. In just about every conceivable area of motorcycle dynamics, weight is indeed the enemy. Which makes big-bore sportbikes—the heaviest performance motorcycles of all —the category needing the most attention.

This fact became the driving force behind the 900 the moment Honda decided to make a full assault on the Open-class weight problem. Using the very latest in computerized modal analysis, the engineers determined the best size, shape and material requirements of virtually every component on the 900. Even the little pieces that usually are taken for granted, including all nuts, bolts and washers, were closely analyzed to determine precisely how light each could be made while still providing sufficient strength, durability and cost-effectiveness.

Every new model goes through a certain amount of such analysis during its development, but the program for the 900 was one of the most intense and thorough ever conducted for a non-racing motorcycle. The end result is an act that other manufacturers will find tough to follow.

Of the many reasons why the CBR900RR project has been such a tremendous success, two in particular stand out as perhaps the most important. One of them is time: The development of the 900 was ongoing for four years, about twice the time usually allotted for taking a new model from drawing board to production line. This allowed the engineers to be much more painstaking in the refinement of' the 900.

The other significant reason is an engineer at Honda R&D named Tadao Baba, the bike's LPL (Large Project Leader. Honda-speak for the person in charge of developing a new model). Typically, project leaders at Japanese motorcycle companies come from purely engineering backgrounds and often have little riding experience. But Baba is an exception; he came from the testing department. where for years he was R&D's chief test rider. And those thousands of hours of saddle time of ten proved invaluable to him and his team in finding solutions to difficult development problems.

This is not to imply that engineers w ho lack riding experience are incapable of developing superb motorcycles; history has proven otherwise. But Baba's experience as a professional evaluator of both on-and off-road machinery gives him a very useful advantage as a motorcycle designer: He has that special feel, that intimate appreciation for the subtleties of motorcycle dynamics, that only an accomplished rider can fully understand.

Baba's background had to have been especially helpful, then, as the team pursued one of the project’s primary goals: to produce the most agile Open-class motorcycle ever built. Success in this area meant not onlv minimizing overall weight, but also distributing much ofthat weight as close as possible to the bike's center of gravity. “Mass centralization." Honda calls it. This concentration of mass reduces a bike's yaw moment, which means it becomes more willing to turn and quickly change direction: it also reduces the roll moment, making the bike easier to bank over into a corner and flick side-to-side.

According to our test-riding consultant. Baba and his crew did their homework here. “The 900 is so much more nimble and responsive than any other Open bike," he said, “that you can't really compare them." He insists that you have to compare the 900's handling to that of a smaller bike such as the CBR600F2, the most-agile and slickesthandling middleweight of all. “The two are very similar in their handling characteristics," he said, “with the 900 just the tiniest bit slower in steering quickness. But in the amount of effort required to initiate a turn and the neutrality of their steering at all lean angles, the two bikes are practicallv indistinguishable."

One of the stiffest challenges the development team faced in its quest for unparalleled lightness and agility was designing an Open-class engine small and light enough. The engine is by far the biggest lump of weight on any bike; and unless that engine is uncommonly light, it is impossible to remove enough weight elsewhere to end up with an uncommonly light motorcycle. Likew ise, if an engine is not made exceptionally short (in height) and narrow. the motorcycle in w hich it resides is not likely to have the roll-moment characteristics necessary for exceptionally quick and nimble handling.

Once again. Honda found the solutions in an intensive, state-of-the-art computer analysis that thoroughly scrutinized every single element of engine design and metallurgy. With that kind of information to guide them, the designers were able to craft the narrowest, lightest, mostcompact Open-class inline-Four ever built.

We were surprised to learn, though, that the ('BR600F2 engine was built with technology developed for the 900. rather than the other way around. The 900 program (which actually started out to build a 750) was well underway when the company discovered it was in desperate need of an all-new machine for the highly competitive— and profitable—600 class. Management decided that work on the 900 would continue uninterrupted, but that the smaller bike would have to be put into production first. I he 600\s designers simply took advantage of the lightweight engine technology that the CBR900RR project had already produced.

That R&D leap-f rogging helps explain how the long, four-year development period of the 900 came to pass. 0 also explains the extreme similarities between the 600 and 900 engines: cam-chain drive at the right side of the motor rather than in the middle, thus allowing a narrower ermine by eliminating one main-bearing journal; cylinder block cast as an integral part of the upper crankcase; an extremely narrow included valve angle of 16 degrees, yielding a very compact combustion chamber; and forwardinclined cylinders with straight-shot intake ports fed bv flat-slide downdraf t carburetors.

One significant difference is in the shape of the 900's intake ports. After completing the 600 engine, R&D found that intake flow and fuel atomization were improved if the “floor (the side closest to the rear of the engine) of the near-vertical intake ports was made relatively flat. I his port shape has been incorporated into the 900. but came too late to be included on the current 600.

Despite the 900 engine's 50-percent greater displacement and 20-percent higher power output compared to the 6001 2's. it is only 10 percent heavier (147 vs. 134 pounds), two inches wider and less than one inch taller. I hat's quite an accomplishment, considering that the F2 engine is the lightest and most compact in the 600 class.

But despite its tiny external dimensions—and a noticeable absence of flywheel inertia, which makes it exceptionally quick-revving—the 900 engine offers authentic big-engine punch, according to the test rider. It churns out potent power at all rpm. not unlike a big Twin, with enough low-rpm urge to make shifting the six-speed gearbox often seem like a waste of time. The engine does not feel peaky at all. although it does perk up a bit between about 4500 rpm and 8500. followed by an even stronger power surge that extends from 8500 up’to the I 1.000-rpm redline. And when kept in its upper-rpm range, the 900 vanishes down the road as only a liter-class bike can — maybe not with quite the relentless ferocity of a ZX-1 I. but certainly at a rate that'll give the big GSX-Rs and FZRsall they can possibly handle.

Besides. I londa's stated goal with the CBR900RR is not to post the industry's fastest top speed or quickest quartermile time; instead, the C'BR is meant to be the quickest thing on two wheels between Point A and Point B when there are lots of corners in between.

Superior handling, in other words, which is something the 900 has in abundance. It can be effortlessly flicked into and out of corners like the 600cc middleweight it so closely resembles. It rails through fast turns with the ease and aplomb that few other bikes can even approach, let alone equal. Says our guest tester. “The 900 offers the secure handling feel of some pretty sophisticated, purpose-built machinery like the Honda RG30 or the FZR 1000-powered Bimota Dieci. But it has far better suspension compliance and steers into corners more easily than the Bimota. feels less top-heavy than the RC30. and has a less-cramped riding position than either of the two."

I his extreme handling competence is no accident.

C omputer studies of the stresses and resonances that a frame must endure helped R&D design an extremely rizzid aluminum main structure. It's a composite of cast, forged and extruded pieces that weighs just 23 pounds—not counting the detachable aluminum rear subframe. The engine is solidly mounted in three places to f unction as a stressed frame member; computer analysis also resulted in a fourth pair of engine mounts—cm the upper crankcase, above the gearbox —being rubber-cushioned to dampen the effects of engine vibration.

There's no innovation to speak of'at the rear end of the 900. where a super-wide but conventional I80/55-VR17 Bridgestone Battlax radial rides on a 5.5-inch-wide wheel. The linkage rear suspension uses a CBR600F'2-style single shock with the usual preload, compression and rebound adjustments. And the swingarm is unremarkable, save for the square-tube, triangulated brace that adds rigidity to the lightweight, tw in-beam structure. I he brace itself is much like those used on various roadracers. but the method of its manufacture is unique to Honda. Instead cd' being bent after extrusion, the brace is formed during extrusion, a technology Honda developed for the Aeura NSX sports car. This technique supposedly allows the finished product to be both stronger and lighter.

At the front end of the 900. there is plenty to talk about. Most obvious is the fork, w hich is of conventional, riizhtside-up design, but with the largest stanchions on record: 45mm in diameter. 2mm larger than what most other performance bikes use. The bigger diameter allows the use of thinner-wali tubing, which nets a gain in strength and a loss in weight. Plus, the increased clamping area of the fatter tubes, combined with a new type of extruded-aluminum slider that allows closer tolerances, provides a greater resistance to radial flexing.

Honda claims that the 900’s complete fork assembly isa few ounces lighter and 10 percent more rigid than the 43mm unit on an RC30, and is slightly less costly to manufacture. Our test consultant fully endorses those claims of exceptional rigidity. He says that when he had the CBR in the midst of all-out braking entering fast, bumpy corners, he never sensed even the slightest amount of fork deflection in any direction.

Another unconventional feature is the CBR’s 16-inch front wheel—a size we all thought had been made obsolete by 17-inch wheels. Mr. Baba said that he started out with the usual 12()mm-wide. low-profile 17-inch radial tire on the front, but was unhappy with the amount of cornering traction it provided, so he tried a 1 30mm width. That gave the needed traction, but the added rubber around the circumference increased the rotational inertia just enough to make the steering a bit heavy and sluggish. He switched to a 1 6-inch wheel (which has less rotational inertia than a I 7 because the mass of the rim is closer to the axle) to lighten the steering, then asked Bridgestone to build a tire that had the desired I 30mm width and the same outside diameter and handling characteristics as a 1 7-incher.

It took a few failed attempts, but Bridgestone finally supplied a relatively high-profile (70-series), 16-inch semi-radial that performs just as well as a low-profile 1 7incher. At this point, though, neither Bridgestone nor Baba is willing to disclose how that feat was accomplished.

However it was done, it apparently works. According to our test adviser, the 900 knifes through fast corners without a trace of front-tire slippage or other unsettling quirkiness. And he claims the Bridgestones stick more tenaciously than any tires he has ever sampled besides softcompound racing slicks. “Even when I had the 900 heeled over so far that there was barely room for my knee between the fairing and the ground,” he said, “the tires clung to the road like electromagnets to a steel plate.”

He also feels that the tires contribute quite a lot to the 900's outstanding ride. The suspension is just taut enough to keep the bike dead-stable during wide-open cornering, and just compliant enough to absorb the punishment of most normal road imperfections. Only the RC30 has a suspension that can match the 900's for that kind of do-itall versatility.

Baba explained that the 45mm stanchion tubes are partly responsible for the fork's exemplary w heel control. The increased diameter of each tube means the damping cartridge inside also can be larger. That results in a greater volume of damping oil which, in turn, allows larger orifices in the damper rods. And larger holes make for smoother and more-consistent damping.

For the most part, the 900's comfort level is not seriously compromised by its ergonomics, which rank somewhere between the mild roadrace tuck of the CBR600F2 and. say. the fairly upright sport-touring position of 1 londa's own VFR750. “I sometimes spent the better part of a f ull day at the controls of the 900,” stated the test rider, “and 1 never got as tired as 1 would have on a GSXR I 100. an FZR 1000 or even an RC30.”

So. based on everything we know about the 900 to this point, the engineers at I londa appear to have succeeded in creating exactly what they intended: the most rational and intelligently designed big-bore performance machine ever built. Instead of taking the conventional route and bolting on a ton of power, they set their sights on loftier goals, ideals such as light weight, mechanical simplicity and. perhaps most admirable of all. balance.

Indeed, this is no off-the-shelf 600 that has had a monster motor shoehorned into it. Despite its light weight and compact size, this is a motorcycle w ith a 120-horsepower chassis to match its 120-horsepower engine: a motorcycle w hose advantages can be enjoyed no matter if it's ridden at low speeds or high: a motorcycle that uses finesse rather than force to get the job done.

Of course, w hether or not the motorcycle you'll be able to buy this coming spring is as magnificent as the one we've described here depends upon how accurately the production-line 900 duplicates the prototype our secret tester enjoyed for five days. If it turns out to be a faithful reproduction, the Open class will never be the same.

And the most notorious enemy of big-bore high performance will have taken the first step down the road to obsolescence.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

December 1991 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

December 1991 By Peter Egan -

Columns

ColumnsTdc

December 1991 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1991 -

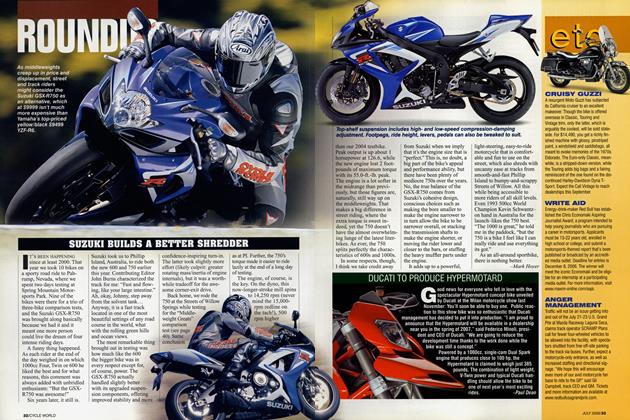

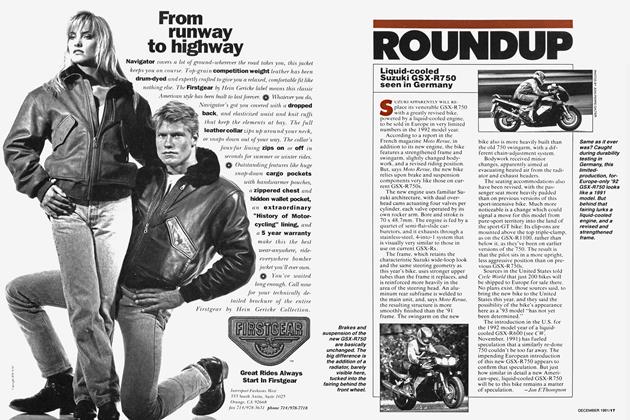

Roundup

RoundupLiquid-Cooled Suzuki Gsx-R750 Seen In Germany

December 1991 By Jon F.Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki Reinvents the Rokon

December 1991 By Jon F. Thompson