North Star Rising

RACE WATCH

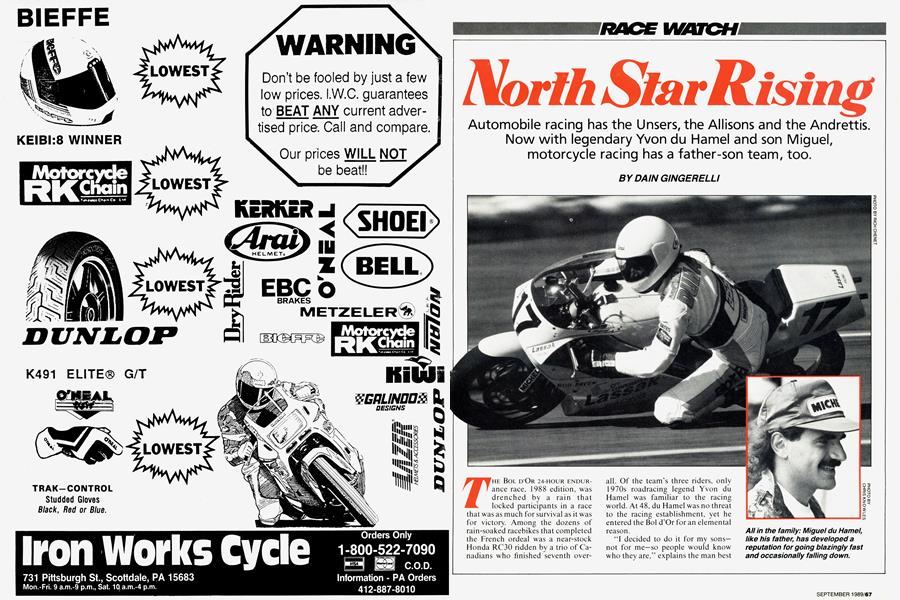

Automobile racing has the Unsers, the Allisons and the Andrettis. Now with legendary Yvon du Hamel and son Miguel, motorcycle racing has a father-son team, too.

DAIN GINGERELLI

THE BOL D’OR 24-HOUR ENDURance race, 1988 edition, was drenched by a rain that locked participants in a race that was as much for survival as it was for victory. Among the dozens of rain-soaked racebikes that completed the French ordeal was a near-stock Honda RC30 ridden by a trio of Canadians who finished seventh overall. Of the team’s three riders, only 1970s roadracing legend Yvon du Hamel was familiar to the racing world. At 48, du Hamel was no threat to the racing establishment, yet he entered the Bol d’Or for an elemental reason.

“I decided to do it for my sons— not for me—so people would know who they are,” explains the man best remembered by American race fans for his exploits—and crashes—aboard the searing Team Kawasaki Triples of the mid-1970s.

Du Hamel’s teammates at Bol d’Or were sons Mario and Miguel. A year later, Miguel, the faster of the two offspring, now is considered by some to be Canada’s best chance for its first-ever world champion roadracer.

Prior to last year’s Bol d’Or, nobody would have considered the youngest du Hamel a threat. He was young and had been roadracing only since mid-1986. Either of those two strikes could quickly lead to strike three: A career-ending, high-speed get-off—not uncommon among enthusiastic riders with big dreams and little experience.

But Miguel doesn't lack talent. Within the span of 1 1 years, after his start as a motocrosser at age 9, he captured several amateur Canadian championships. He turned professional as a teen, and then brother Mario tried roadracing. “He said it was fun,” recalls du Hamel, “so I got involved, too.” He obtained a competition license and, aboard an RZ350, won his first race and

crashed out of his second, the last of the season.

The 1986-87 winter hiatus gave du Hamel adequate time to realize that roadracing—his father’s forte—was also his, and so he prepped his Yamaha for the forthcoming Canadian RZ Cup Championship. He won that title and at season’s end, turned professional.

Du Hamel then landed a ride with> a team campaigning a Kawasaki in Canada’s Superbike championship, but while his sponsors gave him plenty of encouragement and support, they did not understand the long hours of pre-race preparation necessary to produce a winner. By mid-season, the Kawasaki 750 was still the same slow motorcycle du Hamel had started the season with. Indeed, its cylinder heads had never been removed for inspection, and it was through sheer determination and hard riding that du Hamel finished consistently in the top five.

Finally, one of the team owners recognized the need to give the Kaw some high-speed hay. A race kit was added for the final race of the season and du Hamel promptly went out and beat Canada’s best, including Superbike champ Rueben McMurter.

About that time, the du Hamels made their impression on the Bol d’Or crowd, and suddenly the name Miguel du Hamel became worth watching.

The first to acknowledge du Hamel’s potential as Canada’s future roadrace star was former AMA expert Alan LaBrosse, general manager of RACE, a Canadian motorcycleracing sanctioning body, who offered his services as manager for the young du HamelCTalent was what drew my attention to him; plus he’s young and can be well-marketed,”says LaBrosse, who admits that Miguel’s surname has its advantages.“People remember Yvon,” he adds.

The first order of business was to land a 250cc GP ride. Since du Hamel had never ridden a two-stroke roadracer of any consequence, LaBrosse knew none of the top teams would even consider him. So he did the next best thing and contacted John Lassak of Lassak Racing, a privateer team in America. A plumbing contractor by trade, Lassak, like so many other American team owners, must treat his racing endeavors as a weekend hobby instead of as a profession. Even so, his riders get results, including the only non-Team Roberts win in the AMA 250cc Castrol Series last year.

LaBrosse cut a deal for du Hamel to ride a Lassak-prepared 250 at Daytona and the Laguna Seca USGP Because of a parts mix-up, Lassak had to put du Hamel on the team’s 1988 Yamaha TZ250 for both races, leav-> ing a more-competitive Rotaxpowered Aprilia on the sidelines. Despite riding what could be labeled obsolete equipment, du Hamel responded with a steady performance at The Beach, netting eighth place.

At Laguna Seca, du Hamel’s qualifying time was not fast enough to put him into the race, so along with other non-qualifying riders, he was relegated to the Consolation Final—a race among slow guys. Du Hamel won that race, his first victory for Lassak Racing, but would have been happier with a spot in the main event.

A few weeks later, riding the same bike at the Road Atlanta AMA National, du Hamel made amends. As Lassak retells the story, “It was the last lap. He was in fourth place and (former 250 champ) Donnie Greene and (number-one Lassak Racing rider) Alan Carter caught and passed him. I figured that was it. But when they came around for the checkered flag, Miguel was leading them again.

I couldn’t figure out how or where he passed them both, because once you’re on the far side of the track at Road Atlanta, it’s hard to overtake somebody. But he did.”

And now it is two-time AMA 250 champion and Laguna Seca 250 GP winner John Kocinski that du Hamel wants to measure himself against. During the Canada vs. America challenge series at Shannonville Motorsport Park the week after Road Atlanta, du Hamel was looking forward to a showdown with Kocinski. That confrontation was postponed, however, when Kocinski broke a wrist in a crash at Road Atlanta.

Still, by the end of practice at Shannonville, du Hamel was obviously the fastest rider in the 250 class and he won the event’s two 10-lap races. But the real news was that not only did he lower the track record for the 250 class, but his 1:47.63 lap time established an outright track record as well. Aboard a 1988 TZ250, du Hamel shattered the track record— formerly held by a Superbike rider— by 1.6 seconds.

Immediately after the Shannonville races, Suzuki of Canada signed du Hamel to contest that country’s Superbike championship with the latest edition GSX-R750 R-model. Shortly thereafter, du Hamel accepted an offer from Honda HRC to ride in a 200-kilometer endurance race in Japan, where he finished sixth. He then teamed with brother Mario and Australian endurance ace Mel Campbell to finish fourth at the prestigious 24 Hours of Le Mans (see Race Watch, Cycle World, August, 1989).

Not resting on those laurels, du Hamel put in an impressive performance in the 250 class at the Loudon AMA National. With only four laps of practice, all in the rain, du Hamel rode to third place behind the only two riders to win AMA 250cc championships in the past five years—John Kocinski and Donnie Greene.

What remains to be seen is how well the youngest du Hamel will do in upcoming seasons. Can he rise to the echelon occupied by the 500cc GP riders, and if he does, can he learn to cope with the bone-wrenching power of bikes so powerful and fast that only a handful of men can ride them to their full potential?

Du Hamel seems to think so. “After a month of practice (on a 500), I think I can adjust. I like to have lots of horsepower.” Indeed, du Hamel shows no fear of any racebike, even if it puts its power to the rear wheel with all the delicacy of Conan the Barbarian. As he puts it, “It’s fun to ride the big bikes. It’s fun to slide around.”

Perhaps the key word here is fun. Because as history has proven, the racers who have the most fun on the track often are the most successful. Just ask Yvon du Hamel, to this date the greatest pavement racer ever to come out of Canada. But that ranking could soon change. Because Miguel du Hamel is on the rise.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

September 1989 By David Edwards -

Columns

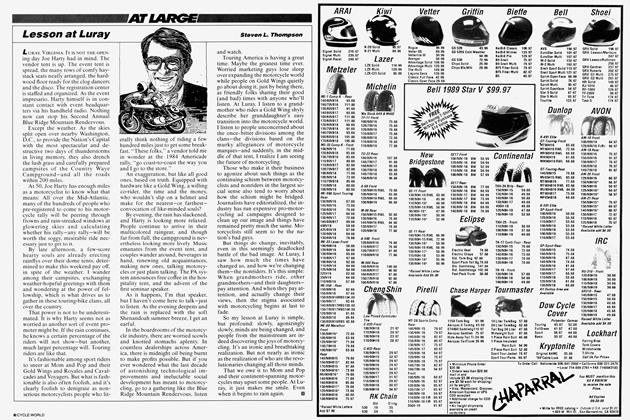

ColumnsAt Large

September 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

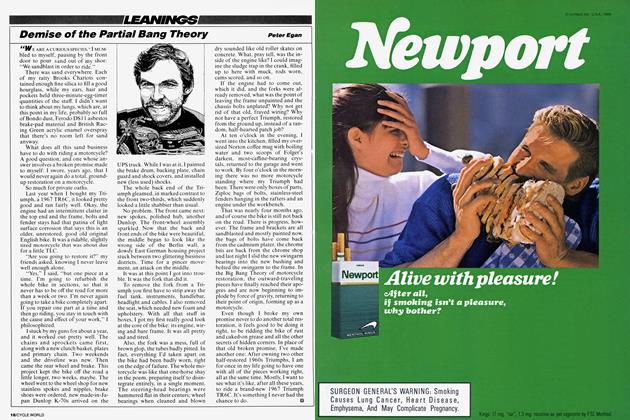

ColumnsLeanings

September 1989 By Peter Egan -

Letters

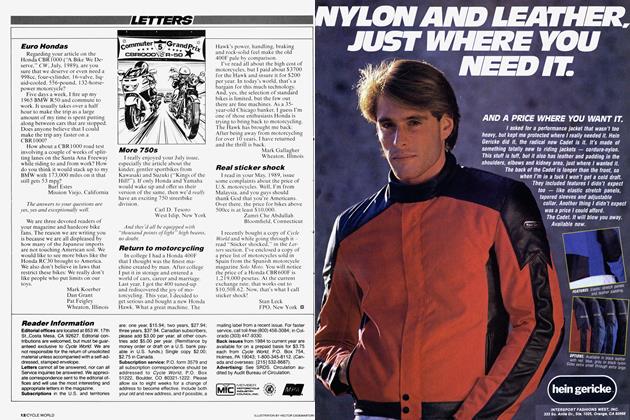

LettersLetters

September 1989 -

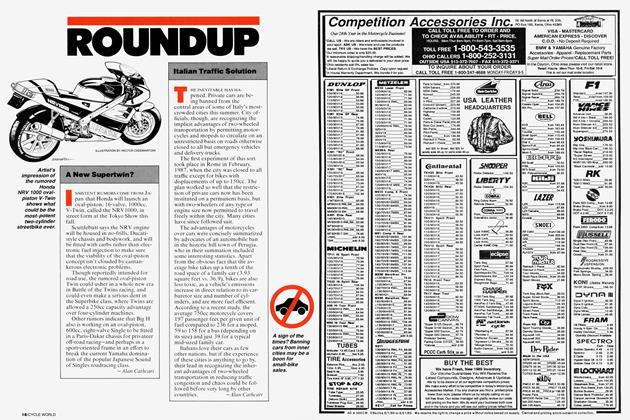

Roundup

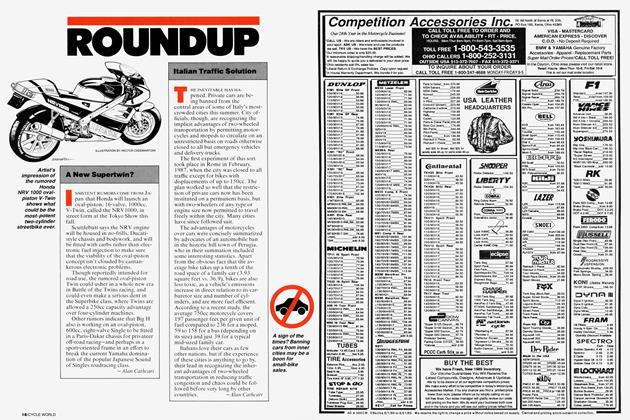

RoundupA New Supertwin?

September 1989 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupItalian Traffic Solution

September 1989 By Alan Cathcart