LEANINGS

Demise of the Partial Bang Theory

Peter Egan

“WE ARE A CURIOUS SPECIES,” I MUMbled to myself, pausing by the front door to pour sand out of my shoe. “We sandblast in order to ride.”

There was sand everywhere. Each of my ratty Brooks Chariots contained enough fine silica to fill a good hourglass, while my ears, hair and pockets held three-minute-egg-timer quantities of the stuff. I didn’t want to think about my lungs, which are, at this point in my life, probably so full of Bondo dust, Ferodo DS11 asbestos brake-pad material and British Racing Green acrylic enamel overspray that there’s no room left for sand anyway.

What does all this sand business have to do with riding a motorcycle? A good question, and one whose answer involves a broken promise made to myself: I swore, years ago, that I would never again do a total, groundup restoration on a motorcycle.

So much for private oaths.

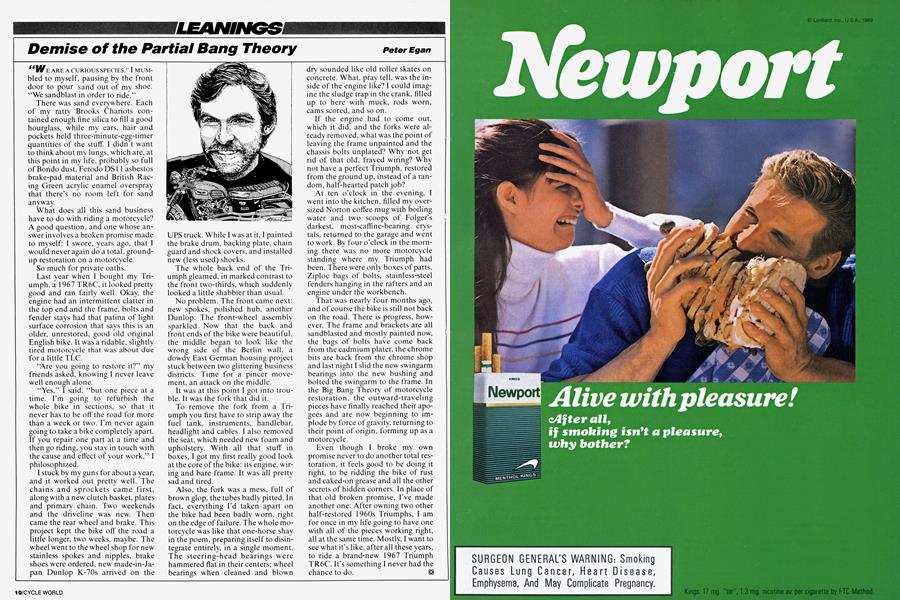

Last year when I bought my Triumph, a 1967 TR6C, it looked pretty good and ran fairly well. Okay, the engine had an intermittent clatter in the top end and the frame, bolts and fender stays had that patina of light surface corrosion that says this is an older, unrestored, good old original English bike. It was a ridable, slightly tired motorcycle that was about due for a little TLC.

“Are you going to restore it?” my friends asked, knowing I never leave well enough alone.

“Yes,” I said, “but one piece at a time. I’m going to refurbish the whole bike in sections, so that it never has to be off the road for more than a week or two. I’m never again going to take a bike completely apart. If you repair one part at a time and then go riding, you stay in touch with the cause and effect of your work,” I philosophized.

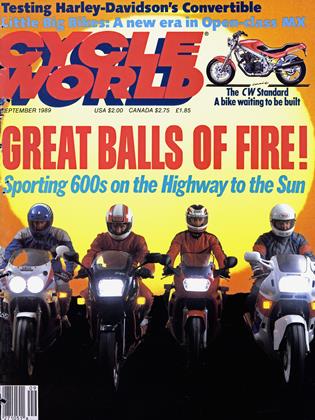

I stuck by my guns for about a year, and it worked out pretty well. The chains and sprockets came first, along with a new clutch basket, plates and primary chain. Two weekends and the driveline was new. Then came the rear wheel and brake. This project kept the bike off the road a little longer, two weeks, maybe. The wheel went to the wheel shop for new stainless spokes and nipples, brake shoes were ordered, new made-in-Japan Dunlop K-70s arrived on the UPS truck. While I was at it, I painted the brake drum, backing plate, chain guard and shock covers, and installed new (less used) shocks.

The whole back end of the Triumph gleamed, in marked contrast to the front two-thirds, which suddenly looked a little shabbier than usual.

No problem. The front came next: new spokes, polished hub, another Dunlop. The front-wheel assembly sparkled. Now that the back and front ends of the bike were beautiful, the middle began to look like the wrong side of the Berlin wall, a dowdy East German housing project stuck between two glittering business districts. Time for a pincer movement, an attack on the middle.

It was at this point I got into trouble. It was the fork that did it.

To remove the fork from a Triumph you first have to strip away the fuel tank, instruments, handlebar, headlight and cables. I also removed the seat, which needed new foam and upholstery. With all that stuff in boxes, I got my first really good look at the core of the bike: its engine, wiring and bare frame. It was all pretty sad and tired.

Also, the fork was a mess, full of brown glop, the tubes badly pitted. In fact, everything I’d taken apart on the bike had been badly worn, right on the edge of failure. The whole motorcycle was like that one-horse shay in the poem, preparing itself to disintegrate entirely, in a single moment. The steering-head bearings were hammered flat in their centers; wheel bearings when cleaned and blown dry sounded like old roller skates on concrete. What, pray tell, was the inside of the engine like? I could imagine the sludge trap in the crank, filled up to here with muck, rods worn, cams scored, and so on.

If the engine had to come out, which it did, and the forks were already removed, what was the point of leaving the frame unpainted and the chassis bolts unplated? Why not get rid of that old, frayed wiring? Why not have a perfect Triumph, restored from the ground up, instead of a random, half-hearted patch job?

At ten o’clock in the evening, I went into the kitchen, filled my oversized Norton coffee mug with boiling water and two scoops of Folger’s darkest, most-caffine-bearing crystals, returned to the garage and went to work. By four o’clock in the morning there was no more motorcycle standing where my Triumph had been. There were only boxes of parts, Ziploc bags of bolts, stainless-steel fenders hanging in the rafters and an engine under the workbench.

That was nearly four months ago, and of course the bike is still not back on the road. There is progress, however. The frame and brackets are all sandblasted and mostly painted now, the bags of bolts have come back from the cadmium plater, the chrome bits are back from the chrome shop and last night I slid the new swingarm bearings into the new bushing and bolted the swingarm to the frame. In the Big Bang Theory of motorcycle restoration, the outward-traveling pieces have finally reached their apogees and are now beginning to implode by force of gravity, returning to their point of origin, forming up as a motorcycle.

Even though I broke my own promise never to do another total restoration, it feels good to be doing it right, to be ridding the bike of rust and caked-on grease and all the other secrets of hidden corners. In place of that old broken promise, I’ve made another one: After owning two other half-restored 1960s Triumphs, I am for once in my life going to have one with all of the pieces working right, all at the same time. Mostly, I want to see what it’s like, after all these years, to ride a brand-new 1967 Triumph TR6C. It’s something I never had the chance to do.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

September 1989 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

September 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

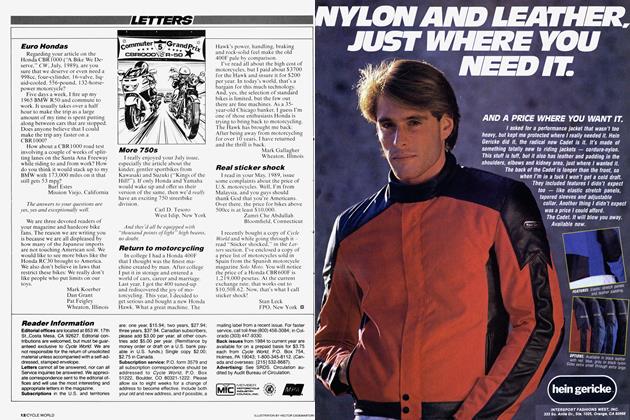

LettersLetters

September 1989 -

Roundup

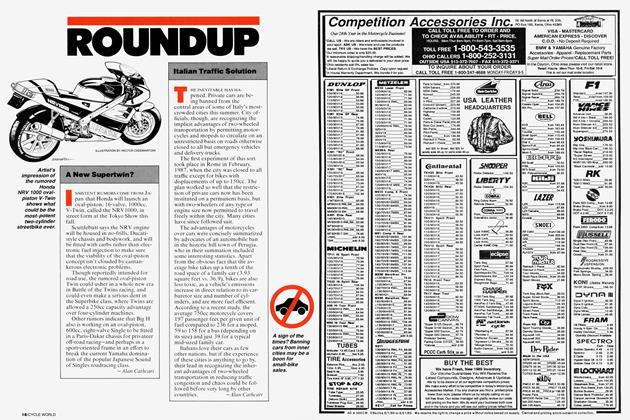

RoundupA New Supertwin?

September 1989 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupItalian Traffic Solution

September 1989 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

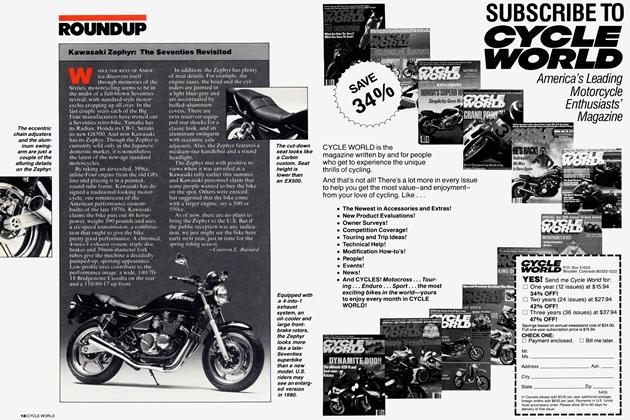

RoundupKawasaki Zephyr: the Seventies Revisited

September 1989 By Camron E. Bussard