AT LARGE

Lesson at Luray

Steven L. Thompson

LURAY, VIRGINIA: IT IS NOT THE OPENing day Joe Harty had in mind. The vendor tent is up. The event tent is spread, the many rows of comfy haystack seats neatly arranged, the hardwood floor ready for the clog dancers and the disco. The registration center is staffed and organized. As the event impresario, Harty himself is in constant contact with event headquarters via his handheld radio. Nothing now can stop his Second Annual Blue Ridge Mountain Rendezvous.

Except the weather. As the skies split open over nearby Washington, D.C., to provide the Nation’s Capital with the most spectacular and destructive two days of thunderstorms in living memory, they also drench the lush grass and carefully prepared campsites of the Country Waye Campground—and all the roads within 200 miles.

At 50, Joe Harty has enough miles as a motorcyclist to know what that means: All over the Mid-Atlantic, many of the hundreds of people who pre-registered to come to his motorcycle rally will be peering through frowns and rain-streaked windows at glowering skies and calculating whether his rally—any rally—will be worth the soggy, miserable ride necessary just to get to it.

By late afternoon, a few-score hearty souls are already erecting rainflys over their dome tents, determined to make this weekend pay off, in spite of the weather. I wander among their campsites, exchanging weather-hopeful greetings with them and wondering at the power of fellowship, which is what drives us to gather in these touring-bike clans, all over the country.

That power is not to be underestimated. It is why Harty seems not as worried as another sort of event promoter might be. If the rain continues, he knows a certain percentage of the riders will not show—but another, much larger percentage will. Touring riders are like that.

It’s fashionable among sport riders to sneer at Mom and Pop and their Gold Wings and Royales and Cavalcades and Voyagers. But what is fashionable is also often foolish, and it’s clearly foolish to denigrate as nonserious motorcyclists people who literally think nothing of riding a few hundred miles just to get some breakfast. “These folks,” a vendor told me in wonder at the 1984 Americade rally, “go coast-to-coast the way you and I go to the store.”

An exaggeration, but like all good ones, based on truth. Equipped with hardware like a Gold Wing, a willing co-rider, the time and the money, who wouldn’t slip on a helmet and make for the nearest—or farthestconvocation of like-minded souls?

By evening, the rain has slackened, and Harty is looking more relaxed. People continue to arrive in their multicolored raingear, and though far from full, the campground is nevertheless looking more lively. Music emanates from the event tent, and couples wander around, beverages in hand, renewing old acquaintances, making new ones, talking motorcycles or just plain talking. The PA system announces free coffee in the hospitality tent, and the advent of the first seminar speaker.

As it happens, I’m that speaker, but I haven’t come here to talk—just to listen. As the evening deepens and the rain is replaced with the soft Shenandoah summer breeze, I get an earful.

In the boardrooms of the motorcycle industry, there are worried scowls and knotted stomachs aplenty. In countless dealerships across America, there is midnight oil being burnt to make profits possible. But if you ever wondered what the last decade of astonishing technological improvements and ineluctable social development has meant to motorcycling, go to a gathering like the Blue Ridge Mountain Rendezvous, listen and watch.

Touring America is having a great time. Maybe the greatest time ever. Worried marketing guys lose sleep over expanding the motorcycle world while people on Gold Wings quietly go about doing it, just by being there, as friendly folks sharing their good (and bad) times with anyone who’ll listen. At Luray, I listen to a grandmother who rides a Gold Wing shyly describe her granddaughter’s easy transition into the motorcycle world. I listen to people unconcerned about the once-bitter divisions among the clans—the divisions based on the murky allegiances of motorcycle marques—and suddenly, in the middle of that tent, I realize I am seeing the future of motorcycling.

Those who make it their business to agonize about such things as the continuing schism between motorcyclists and nonriders in the largest social sense also tend to worry about how the schism might be bridged. Journalists have editorialized, the industry has run expensive pro-motorcycling ad campaigns designed to clean up our image and things have remained pretty much the same. Motorcyclists still seem to be the nation’s bad guys.

But things do change, inevitably, even in this seemingly deadlocked battle of the bad image. At Luray, I saw how much the times have changed us, and how we’re changing them—the nonriders. It’s this simple: When grandmothers ride, other grandmothers—and their daughters— pay attention. And when they pay attention, and actually change their views, then the stigma associated with motorcycling begins at last to fade.

So my lesson at Luray is simple, but profound: slowly, agonizingly slowly, minds are being changed, and people from the mainstream are indeed discovering the joys of motorcycling. It’s an ironic and breathtaking realization. But not nearly as ironic as the realization of who are the revolutionaries changing all those minds.

That we owe it to Mom and Pop and their continent-spanning motorcycles may upset some people. At Luray, it just makes me smile. Even when it begins to rain again.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

September 1989 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

September 1989 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1989 -

Roundup

RoundupA New Supertwin?

September 1989 By Alan Cathcart -

Roundup

RoundupItalian Traffic Solution

September 1989 By Alan Cathcart -

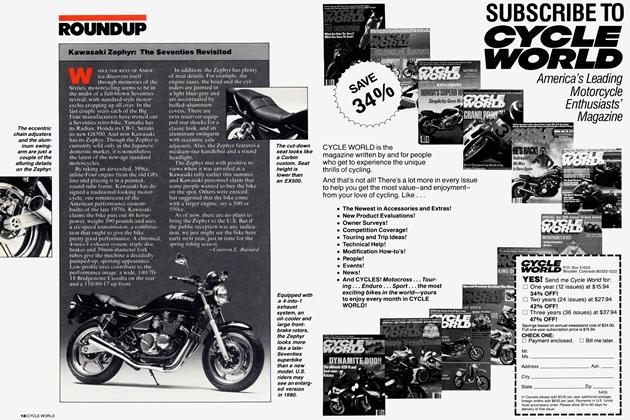

Roundup

RoundupKawasaki Zephyr: the Seventies Revisited

September 1989 By Camron E. Bussard