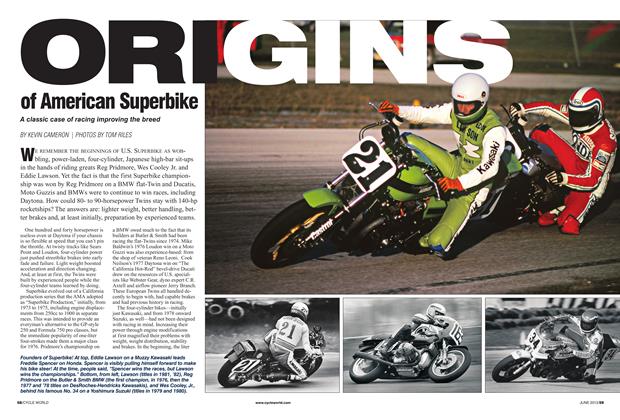

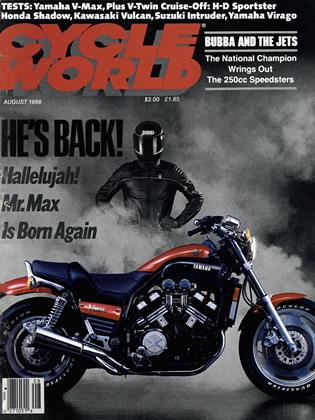

BUBBA AND THE 250S

Of small sportbikes, national champions and California wines

DAVID EDWARDS

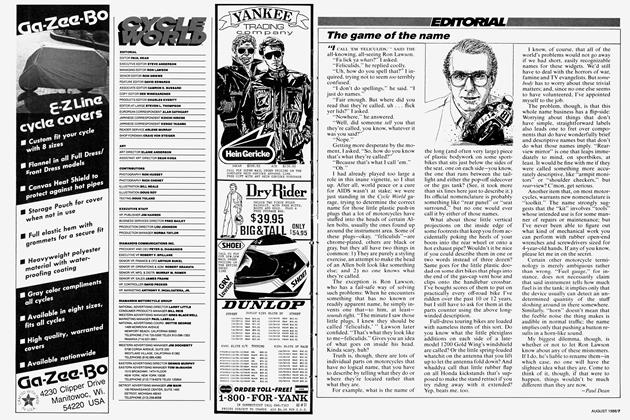

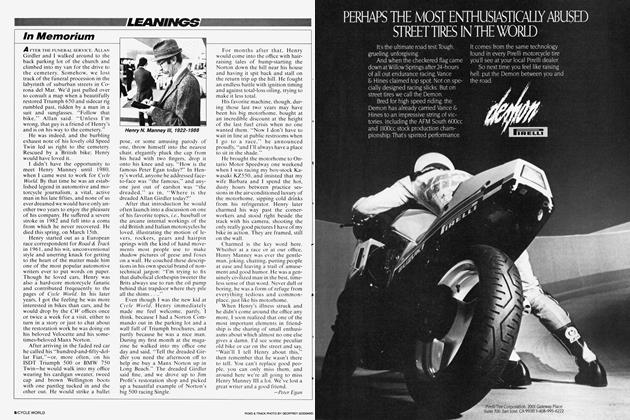

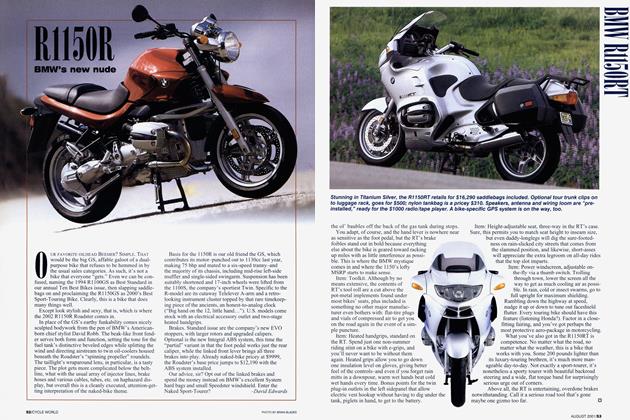

CLEARLY, BUBBA SHOBERT WAS NOT A HAPPY MAN. And I couldn't really blame him. It'll be great, we had told him. You've got three weeks between races and we've got these three 250cc sportbikes. We'll truck them up to your house and then we'll spend a half-day riding up the coast before turning east and heading for the Napa Valley. Great roads there and some of the best vineyards in America; we'll get to do a little winetasting, as well. Whaddya say?

Shobert said yes, but by the time Associate Editor Camron Bussard and I pulled into his driveway, he was looking for a way to bow out. The weather had something to do with it: The heaviest rainstorm in a year had socked in most of California, and the three-day forecast called for more of the same.

Told that Plan B was to load everyone into our Ryder rental van, head straight for the Napa Valley and pray for blue skies, Shobert’s enthusiasm remained at low ebb. “Well, I’ve ridden in worse,” the three-time Grand National champion said, although looking around at his 16valve Mercedes 190 and his condo-sized motorhome, I knew it hadn’t been in the recent past.

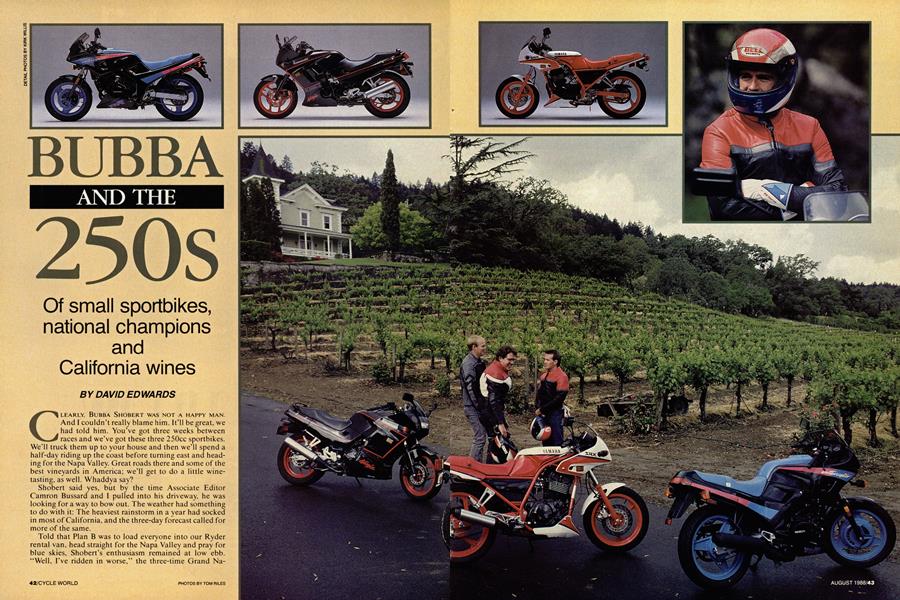

Four hours later, after a Taco Bell lunch and a stop-andgo slog through San Francisco, we were in the Napa Valley, still being assaulted by legions of raindrops. Grabbing his luggage from the back of the van, Shobert got his first good look at the three motorcycles we were supposed to be riding—a Honda Interceptor 250, a Kawasaki Ninja 250 and a Yamaha SRX250. Looking suitably dour, Shobert delivered a verbal knockout punch. “My first job for a magazine and you guys have me riding girls' bikes. I’m surprised they even have gas tanks; I thought they’d be step-throughs.”

He paused just long enough for Camron and me to start feeling uncomfortable, then burst into laughter and shot us a just-kidding-guys wink of the eye.

Although women make up less than 10 percent of the U.S. motorcycling population, they purchase about 25 percent of the 250cc sportbikes. But you don’t have to be female to appreciate a good 250’s finer points, things like light weight, easy handling and a low seat. Even Bubba Shobert is a fan, and not just of the 1 50-mile-an-hour 250cc roadracers that carried him to fifth-place finishes at Daytona and Laguna Seca. He once owned a Honda NS250, a street-legal, two-stroke streaker sold only in Japan, and he is currently awaiting the delivery of a Honda NX250 dual-purpose bike. “It seems like when I put on a helmet. I'm going to work," says Shobert, his Lubbock, Texas, twang only slightly softened by two years in central California. (Shobert owns a house and 10 acres in Carmel Valley. 20 minutes inland of the Laguna Seca racetrack.) "So, when I go street riding, I do it strictly for recreation, just to see the scenery and enjoy the ride. I like small streetbikes, especially when you just want to jump on something and gO to the store; 750s are just too big for that," he says, referring to his limited-edition Honda RC3O, which he recently purchased for $15,000. "It's fun for someone who rides big bikes to step down and ride something to its full potential. On a 250 you can ride hard and still not be going too fast; everything happens at a reduced pace.”

Small streetbikes are making a strong comeback after years spent languishing; and while 250s are available as dual-purpose bikes and cruisers, it’s the sportbike derivatives—notably, the Ninja and the Interceptor—that have stirred the most interest. “Those bikes have a lot of style,” says a Honda/Yamaha/Kawasaki dealer whose shop is near the Cycle World offices. “They’re look-at-me motorcycles, perceived as high-tech, flashy and state-of-the-art.”

Also fueling the quarter-liter resurgence are the purchase prices and insurance costs of larger bikes. As 600cc sportbikes edge closer and closer to the $5000 mark and insurance premiums become unbearable, the 250s become more and more attractive. As our dealer puts it, “The 250 market is here to stay. I’m glad that the industry has finally realized it needs a product line that its market can afford.”

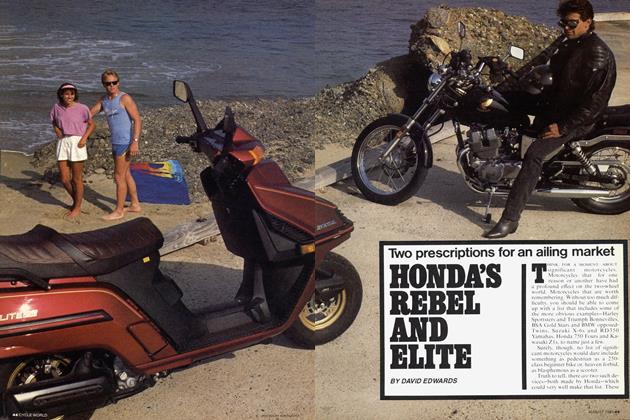

The most affordable of the sporting 250s is Yamaha’s SRX250. Introduced in 1987, the SRX isn’t offered as a 1988 model, but if you’re interested in the red-and-white beauty there are still plenty left in dealerships around the country. Our neighborhood dealer has more than a dozen left, each with $500 knocked off the original $2199 asking price. “I’m not running a museum here,” he says, “I've got to sell them.”

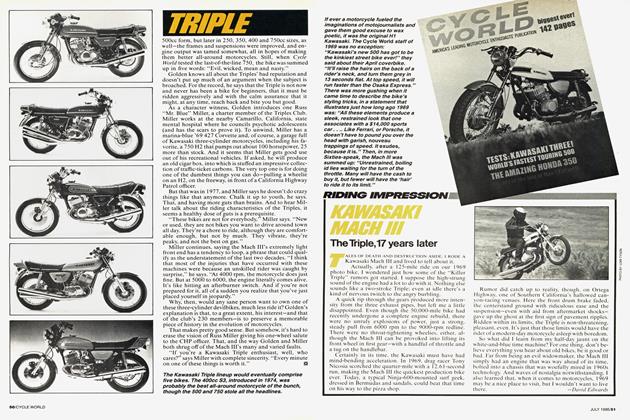

Part of the SRX’s problem can be traced to its performance, or lack thereof, at least compared to the other sport 250s. As Shobert put it, “The Yamaha is just in a different class altogether; it’s hard to compare it to the other two bikes.” When you do stack it up against the Ninja and Interceptor in the standard performance categories, it’s easy to see what Shobert means: Wrung out, the SRX will do 78 miles an hour, 20 miles an hour down on the competition; in the quarter-mile, it comes across the line about two-and-a-half seconds later and 1 5 miles an hour slower.

Considering the SRX’s engine, that speed deficit shouldn’t come as too much of a surprise. It’s a slogger of an air-cooled Single, whereas the two other bikes are highspinning, liquid-cooled Twins; and not even a little technical help from double overhead cams and four valves can bring the SRX’s performance up on par with the others.

Still, the Yamaha has some points in its favor. At 303 pounds dry, it feels 10-speed light around town. Thanks to the engine’s counterbalance^ it’ll run comfortably at freeway speeds. With compliant suspension and surprisingly roomy ergonomics (only the too-thin seat causes bother), it’s a pleasant, if somewhat slow, place to spend an afternoon. And even when ridden with a heavy throttle hand, the SRX gets nearly 70 miles to a gallon of fuel.

The SRX250’s most important advantage over the Ninja and Interceptor, though, may be an outgrowth of its cold reception in the marketplace. For riders who aren’t looking for the latest in 250-class rocketships, who just want a good small motorcycle, almost any Yamaha dealer will be glad to part with an SRX for about half of what a Honda or Kawasaki dealer would want for his 250.

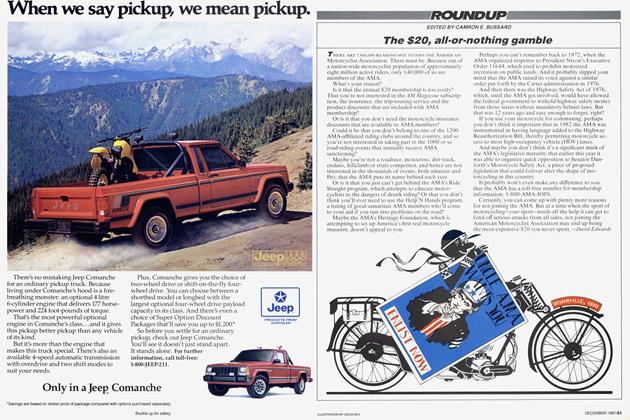

In 1986, Kawasaki took a gamble. It introduced a $2300 250cc sportbike at a time when Honda’s 250 Rebel cruisers were selling like hotcakes at $1500. Two years later, Kawasaki is still reaping the jackpot, even though the new Ninja 250’s suggested pricetag has swelled $500 to $2799. “The Kawasaki is a dynamite seller,” says our local dealer. “In the past three months I’ve sold two Interceptor 250s and maybe 30 Ninjas.” If you can even find an ’88 Ninja 250 these days, expect to pay at least $200 over list for it.

Styling has a lot to do with the Ninja’s success. For 1988, the baby Ninja was redesigned to have a fuller fairing and different bodywork, and it now passes for a 600 or even a 750 at a quick glance.

Mechanically, the bike has been altered, as well, but

with mixed results. The 1988 model’s suspension has been softened, making the ride around town (where studies show most 250cc motorcycles spend their time) downcomforter soft. But if you buy your Ninja for spirited flings in the back country, you’ll have to deal with a front end that dives, a rear shock that isn’t quite up to the task and a sidestand that zings the asphalt a bit too easily.

Kawasaki’s redesign team may not have dug deep enough in the suspension department, but they made up for it with the engine. The ’86 and ’87 versions of the Ninja were powered by a paradox of an inline-Twin: redlined at 14,000 but as seemingly slow-revving and unexciting as a trials bike’s engine. Well, forget all that for 1988. Thanks to a higher compression ratio, straighter intake tracts, a less-restrictive exhaust system and a lighter crankshaft, the new Ninja makes three horsepower more than the old and is as rev-happy as anything sold on two wheels.

Actually, the Ninja doesn’t just like to spin its tach needle, it has to. The powerband remains tucked-in and snoring most of the time and doesn’t even take wake-up calls until 10,000 rpm. An accomplished rider can play that powerband like a Stradivarius, but Shobert raised a good point about the Ninja’s engine characteristics. “I really like the bike, but I don’t feel that the power range is in the right place for a beginning rider. A learner’s not going to feel good about running at that high an rpm.”

Of course, entry-level riders aren’t the only ones buying the Ninja. Kawasaki’s registration records indicate that the average 250 Ninja buyer already has five to six years of riding experience. If the Ninja’s sales success is any indication, maybe all motorcycles should come with just as narrow—and as entertaining—a powerband.

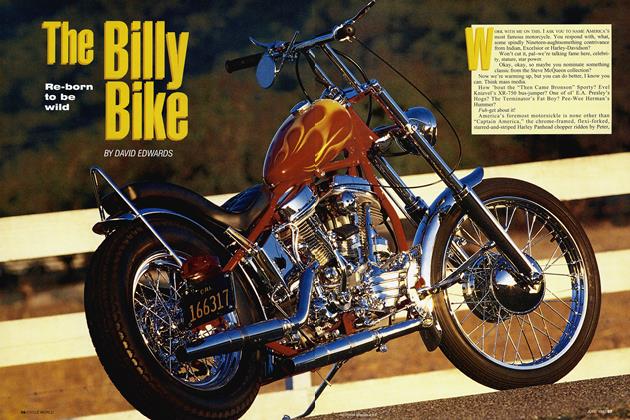

The Honda representative was being unusually frank. “We learned something from Kawasaki,” he admitted. “The Ninja proved there is a market for 250 sportbikes in the U.S.” The Interceptor VTR250 is Honda’s response.

The 250 Interceptor has been sold in Japan for five years, so Honda didn’t have to spend long hours at the drawing board to come up with its Ninja-battler—although it did send a team of marketing researchers scouring the country, asking 16to 25-year-olds their opinions on different color schemes. The two most popular choices— black with pink-and-blue accents, and white with blue accents—set the Honda apart from the more traditionally colored Ninja and SRX. “It’s almost like a fashion accessory,” states a Honda official, “It says, ‘I’m fast and I’m cool.’ ”

Powered by a 90-degree V-Twin, the Interceptor is very close to the Ninja in terms of outright performance (97 vs. 98 miles per hour in top speed, 14.87 vs. 14.86 seconds in the quarter-mile), despite weighing 16 pounds more (347 vs. 331 pounds). It’s in the area of powerbands, though, where the VTR is a peg up on the Ninja. Redlined at 13,500 rpm, the Honda, like the Kawasaki, needs to be spun into the five-figure range to make serious horsepower; but unlike Brand K’s 250, the Interceptor doesn’t mind a little lugging. It’ll pull with some urgency as low as 6000 rpm, and in top-gear roll-on contests from cruising speeds, the Honda quickly puts distance on the Kawasaki.

That powerband translates into a less-frantic, more-relaxing in-town experience for the Interceptor rider, although his bike’s suspension is tuned to be just a little stiffer than the Ninja’s and doesn’t provide quite as Seville-like a ride. That added tautness is evident when tossing the bike hard into corners, where the VTR is more at home than the Ninja. Only the Honda’s unusual, inboarddisc front brake isn’t up to snuff; it feels vague and doesn’t generate the stopping power of the Ninja’s more-conventional front binder. Shobert agreed, saying, “The Interceptor felt real good, except for the front brake. But, then, for a first-time rider, the bike’s got all the front brake he or she really needs.”

The price to be paid for the Honda’s all-around abilities hits an Interceptor buyer right in the checkbook. At $3298, VTR is $500 dearer than the Ninja, although as previously noted, the Kawasaki’s popularity means that almost no one is selling Ninja 250s for list price. So if you don’t mind digging just a little deeper into the savings account, Honda will be glad to provide you with a 250 that is trendy, exciting and versatile.

Shobert sized up his prey coolly, as if getting ready to pull off a last-lap pass at the San Jose Mile, then made his move. “Ladies, may we offer you some champagne? We’re celebrating our first mud bath.”

Indeed, an hour earlier we had been encased in the smelly, mineral-laced goop for which the Napa Valley town of Calistoga is famous. The women seated at the table next to us fell heavily for Shobert’s Texas-tinged opening line and said yes.

Calistoga may have its mud, but the rest of the area is famous for a somewhat tastier liquid. More than 50 wineries make their home in the 30-mile-long valley located about an hour’s drive north of San Francisco. We’d set aside a half-day for wine-tasting, and since motorcycles and alcohol don’t mix (but limousines and company credit cards do), we did our vineyard-hopping nestled safely in the back of a black stretch Volvo.

Actually, our first visit to a vineyard took place earlier in the day when photographer Tom Riles tentatively rang the bell at the St. Clement winery to ask if we could use their gothic-style house as a backdrop. Instead of being shooed away by an underling, we were welcomed with open arms by James Heinemann, the sales manager and a long-time dirt-bike rider. After the photo shoot, Heinemann took us on a private tour that ended in the cellar, where he explained the intricacies of wine tasting. Shobert was eager to put the newfound information to good use: “The next time I’m in victory circle I’m going to open the champagne, look at the cork, and then send the bottle back.”

The Chateau Montelena winery, famous for its cabernet sauvignon, was next on our tour, and Van Williamson, the cellarman, treated us to a glass of the hearty red wine as he explained his company’s philosophy. “The quality of the grape is everything,” he said, “Extraordinary wines can only be made from extraordinary grapes.” The sun, soil and water of the Napa Valley are so conducive to growing extraordinary grapes that a prime acre can fetch as much as $40,000, claims Williamson.

Our last stop was at the Stony Hill winery, a small operation with a reputation for making great chardonnay. Run by Mike Chelini, who lists among his hobbies ATV riding, Stony Hill isn’t open to the public, but St. Clement’s Heinemann thought a visit by a couple of magazine guys and a racer might be appreciated.

He was right. After we sampled some wine in the storage room, Chelini invited us up to his 100-year-old farmhouse where we uncorked an impressive number of wine bottles, being careful, of course, to cleanse our palates with shots of tequilla and cans of Budweiser. When Riles, Bussard and I finally wobbled out to take the limousine back, Shobert was in such fine fettle that he decided to stay. He didn’t get back to the hotel until 4 a.m.

On an early-morning photo shoot just a few hours later, Shobert was looking decidedly green around the gills, and a quote from the 19th-century English poet Lord Byron came to mind:

Let us have wine and women, mirth and laughter.

Sermons and soda water the day after.

Shobert wasn’t quite as lyrical when I mentioned that we might have time to take in another winery or two before leaving. “No more,” he pleaded, “I’d rather ride the SRX in next year’s Daytona 200 than have another glass of wine.”

All three of the 250cc sportbikes currently being sold in America have their strengths and weaknesses. The Yamaha SRX just isn’t modern enough or quick enough for a market that still craves performance. What the bike does have going for it is a very low price, lower even than that of most 200cc scooters. The Kawasaki Ninja has its hot-rod heart wrapped in Sunday-go-to-meetin’ suspension rates, but with a relatively inexpensive upgrade of tires, fork and shock, it could be the all-time king of tight roads. The Honda Interceptor 250, stock for stock, is the best 250 sportbike to be had. Its engine makes it better in-town, and its suspension makes it better in the canyons than the Ninja, although $3300 is a lot to pay for those advantages.

The real winner here, though, is the American motorcyclist. For the first time since the sport took off in the Sixties and Seventies, it’s possible to buy and ride a sub500cc bike and not feel like Charlie Brown peering into his trick-or-treat bag on Halloween (“I got a rock”).

Shobert summed the class up nicely when he said, “None of these machines are what you’d call high-performance motorcycles, but they do give you that look and that feel. They’re pretty neat.” E3

View Full Issue

View Full Issue