UP FRONT

Adventures in riding

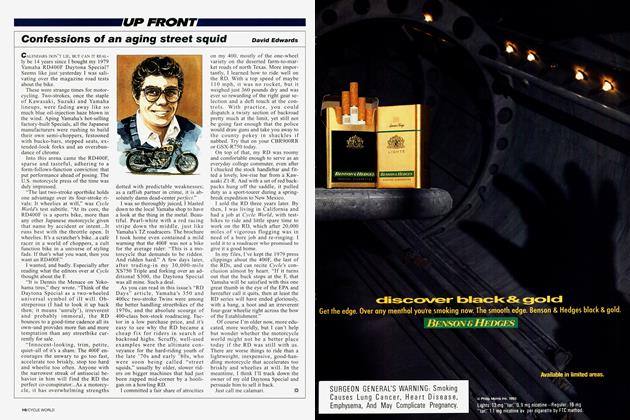

David Edwards

THIS TIME, I WAS HAND-IN-THE-cookie-jar, lock-him-up-and-throw-away-the-key guilty. Not only had I just executed a blatantly felonious pass on a dawdling Dodge van, but I’d done it in plain view of a California Highway Patrol officer and, worse, the motorcycle I’d done it on wasn’t even legal on U.S. streets.

‘it wouldn’t help to say I was sorry,” I feebly offered to the approaching officer.

“Sorry? You do know what a double yellow line means, don’t you?” came the stern reply.

“Well, yeah, but that guy was really going slow, and . . ..”

The ensuing lecture on the protocol of passing was bad enough, but I knew it would pale in comparison to the sermon I’d get when the officer radioed in the bike’s license plate number and found out that while it had been issued to a lowly, 250cc dual-purpose bike, it was now bolted to something much different: a Canadian-spec Honda RC30.

To my astonishment, though, the officer didn’t ask for the bike’s papers, which, of course, I didn’t have. Instead, I was handed back my driver’s license, with an admonishment to, “Take it easy, relax, enjoy the scenery. After all, that’s why you took this road wasn’t it?”

“Uh, yes,” I lied.

“No you didn’t; you came up here to haul ass. Just be careful where you do it.”

If ever there was a road made for hauling ass, California’s Pacific Coast Highway is it. Built 50 years ago with great effort, the road snuggles against the jagged California coastline, offering sweeping corners and splendid vistas.

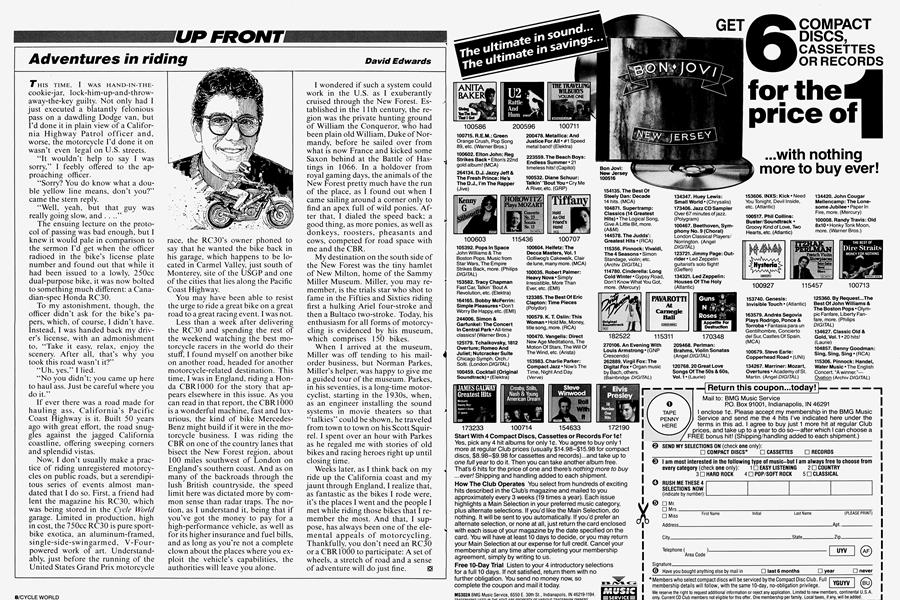

Now, I don’t usually make a practice of riding unregistered motorcycles on public roads, but a serendipitous series of events almost mandated that I do so. First, a friend had lent the magazine his RC30, which was being stored in the Cycle World garage. Limited in production, high in cost, the 750cc RC30 is pure sportbike exotica, an aluminum-framed, single-side-swingarmed, V-Fourpowered work of art. Understandably, just before the running of the United States Grand Prix motorcycle race, the RC30’s owner phoned to say that he wanted the bike back in his garage, which happens to be located in Carmel Valley, just south of Monterey, site of the USGP and one of the cities that lies along the Pacific Coast Highway.

You may have been able to resist the urge to ride a great bike on a great road to a great racing event. I was not.

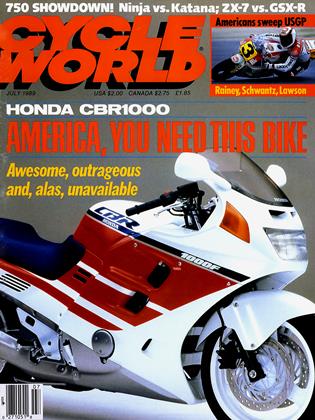

Less than a week after delivering the RC30 and spending the rest of the weekend watching the best motorcycle racers in the world do their stuff, I found myself on another bike on another road, headed for another motorcycle-related destination. This time, I was in England, riding a Honda CBR1000 for the story that appears elsewhere in this issue. As you can read in that report, the CBR 1000 is a wonderful machine, fast and luxurious, the kind of bike MercedesBenz might build if it were in the motorcycle business. I was riding the CBR on one of the country lanes that bisect the New Forest region, about 100 miles southwest of London on England’s southern coast. And as on many of the backroads through the lush British countryside, the speed limit here was dictated more by common sense than radar traps. The notion, as I understand it, being that if you’ve got the money to pay for a high-performance vehicle, as well as for its higher insurance and fuel bills, and as long as you’re not a complete clown about the places where you exploit the vehicle’s capabilities, the authorities will leave you alone. I wondered if such a system could work in the U.S. as I exuberantly cruised through the New Forest. Established in the 11th century, the region was the private hunting ground of William the Conqueror, who had been plain old William, Duke of Normandy, before he sailed over from what is now France and kicked some Saxon behind at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. In a holdover from royal gaming days, the animals of the New Forest pretty much have the run of the place, as I found out when I came sailing around a corner only to find an apex full of wild ponies. After that, I dialed the speed back; a good thing, as more ponies, as well as donkeys, roosters, pheasants and cows, competed for road space with me and the CBR.

My destination on the south side of the New Forest was the tiny hamlet of New Milton, home of the Sammy Miller Museum. Miller, you may remember, is the trials star who shot to fame in the Fifties and Sixties riding first a hulking Ariel four-stroke and then a Bultaco two-stroke. Today, his enthusiasm for all forms of motorcycling is evidenced by his museum, which comprises 150 bikes.

When I arrived at the museum, Miller was off tending to his mailorder business, but Norman Parkes, Miller’s helper, was happy to give me a guided tour of the museum. Parkes, in his seventies, is a long-time motorcyclist, starting in the 1930s, when, as an engineer installing the sound systems in movie theaters so that “talkies” could be shown, he traveled from town to town on his Scott Squirrel. I spent over an hour with Parkes as he regaled me with stories of old bikes and racing heroes right up until closing time.

Weeks later, as I think back on my ride up the California coast and my jaunt through England, I realize that, as fantastic as the bikes I rode were, it’s the places I went and the people I met while riding those bikes that I remember the most. And that, I suppose, has always been one of the elemental appeals of motorcycling. Thankfully, you don’t need an RC30 or a CBR 1000 to participate: A set of wheels, a stretch of road and a sense of adventure will do just fine.