Behind Pit Wall

RACE WATCH

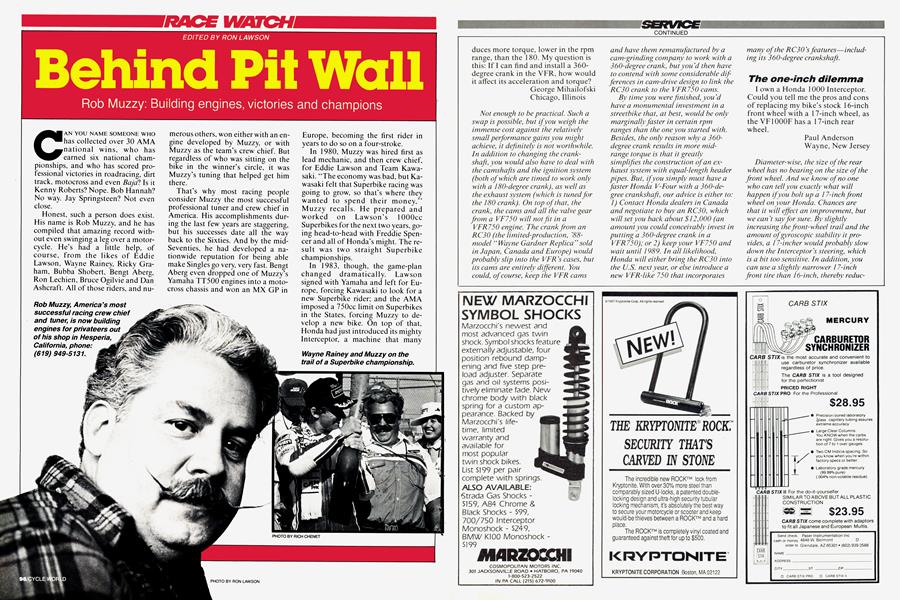

Rob Muzzy: Building engines, victories and champions

RON LAWSON

CAN YOU NAME SOMEONE WHO has collected over 30 AMA national wins, who has earned six national championships, and who has scored professional victories in roadracing, dirt track, motocross and even Baja? Is it Kenny Roberts? Nope. Bob Hannah? No way. Jay Springsteen? Not even close.

Honest, such a person does exist. His name is Rob Muzzy, and he has compiled that amazing record without even swinging a leg over a motorcycle. He’s had a little help, of course, from the likes of Eddie Lawson, Wayne Rainey, Ricky Graham, Bubba Shobert, Bengt Aberg, Ron Lechien, Bruce Ogilvie and Dan Ashcraft. All of those riders, and numerous others, won either with an engine developed by Muzzy, or with Muzzy as the team’s crew chief. But regardless of who was sitting on the bike in the winner’s circle, it was Muzzy’s tuning that helped get him there.

That’s why most racing people consider Muzzy the most successful professional tuner and crew chief in America. His accomplishments during the last few years are staggering, but his successes date all the way back to the Sixties. And by the midSeventies, he had developed a nationwide reputation for being able make Singles go very, very fast. Bengt Aberg even dropped one of Muzzy’s Yamaha TT500 engines into a motocross chassis and won an MX GP in Europe, becoming the first rider in years to do so on a four-stroke.

In 1980, Muzzy was hired first as lead mechanic, and then crew chief, for Eddie Lawson and Team Kawasaki. “The economy was bad, but Kawasaki felt that Superbike racing was going to grow, so that’s where they wanted to spend their money,’’ Muzzy recalls. He prepared and worked on Lawson’s lOOOcc Superbikes for the next two years, going head-to-head with Freddie Spencer and all of Honda’s might. The result was two straight Superbike championships.

In 1983, though, the game-plan changed dramatically. Lawson signed with Yamaha and left for Europe, forcing Kawasaki to look for a new Superbike rider; and the AMA imposed a 750cc limit on Superbikes in the States, forcing Muzzy to develop a new bike. On top of that, Honda had just introduced its mighty Interceptor, a machine that many thought would make an unbeatable racebike. It was going to be a tough season, indeed.

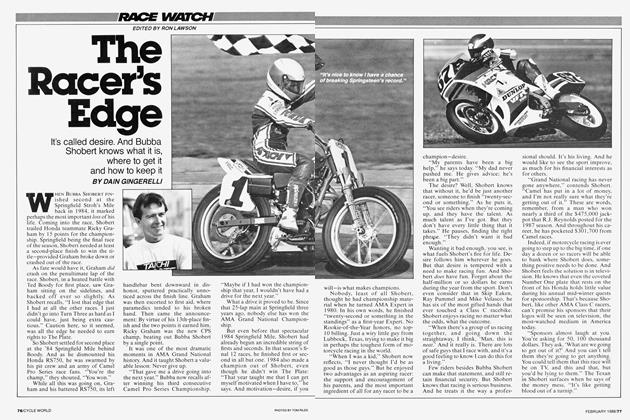

Eventually, it all came together, even though the rider chosen to carry Kawasaki’s colors was Wayne Rainey, a dirt-tracker who had just turned roadracer, and even though Muzzy had to try to make the seemingly dated GPz750 into a winner. “I never worked so hard in my life, and I never want to work that hard again,” laughs Muzzy today. “At the beginning of the year we had a bike that handled, but we were down on power. By mid-year, though, we got the power to where it was competitive. We already had a bike that handled better, so we caught Honda with their pants down. In that part of the year there’s a race almost every weekend, so they didn’t have much time to improve the bike. It worked to our advantage. Between Wayne’s tenacity and the fact that we never gave up, we caught and passed Honda.”

Much to Muzzy’s dismay, Kawasaki rewarded that effort by dismantling the race team in 1984. “It was a corporate decision. Even Kawasaki couldn’t believe that we won the championship. They figured that we had no chance of pulling it off again, so with the poor economy, they killed the race effort.”

Muzzy was prepared to settle down into a new job at Kawasaki as ATV coordinator. But Honda, wanting to get serious about dirt-track racing, had been impressed with Muzzy’s abilities and made him an offer he couldn’t refuse. So, after just a week in his new position at Kawasaki, Muzzy pulled up stakes and switched camps.

Muzzy became Crew Chief, Honda Research and Development, and began immediately to develop the powerful but flawed Honda dirttrack V-Twin. At that point, everyone knew the Honda had potential, but it was hard to handle, and its race results were spotty. “It was a good engine, very well designed,” Muzzy says. “Actually, it was a pretty easy project; it needed smoother power and more flywheel.” With Ricky Graham and Bubba Shobert on board, the Hondas took first and second in the Camel Pro Series that year.

Muzzy still prefers working on roadracers, though. “With dirt-trackers, you have to worry about traction; roadracers are more fun. You really get to go for the power.”

His stay at Honda had him applying his talents to a wide variety of projects. In addition to his dirt-track success, Muzzy developed the 125cc motocross engine that Ron Lechien used to win the 125 national motocross championship in 1985. That being the last year in which one-off works bikes would be allowed, Honda wanted to get a head start on making the production 125 competitive, so Lechien raced a works chassis with a production-based motor developed by Muzzy. The Muzzy magic was then applied to the XR600 motor, which was used in dirt track racing.

During Muzzy’s last two seasons at Honda he was a contract employee, supervising Wayne Rainey’s bid for the Superbike championship. And with Rainey winning the title in 1987, Muzzy saw history repeat itself: The racing program was dismantled, and Rainey left to ride in Europe. “I was prepared for it,” says Muzzy. “Over the last few years I’ve been collecting machine tools, because I knew that eventually I would have to go into business for myself.”

Which is exactly what Muzzy is doing at present. His career has come full circle, and now he finds himself doing much the same kind of work he did before his seven-year stint at creating champions for the Japanese companies. But one thing is different. “I do things the Japanese way now,” he says. “You can see it in every mechanic who has left a Japanese company; it’s a different way of doing things, a better way. Where I would once make a bracket out of scrap steel, now I’ll carve one out of aluminum on the mill.”

Muzzy’s goal is to offer a “factory” level of preparation to the privateer. “I used to hear it all the timepeople would point at us and say ‘how can we compete against them, they’re factory.’ But there’s nothing I did at Honda or Kawasaki that I couldn’t do right here. Some things are harder, like gear-ratio changes, but for the most part, I could build any of those racing engines out of a shop this size.”

So, most of his time now is spent working on projects for the “privateer” classes in racing, such as the Supersport class. Muzzy is working on kits for the Honda Hurricane 600 and the Suzuki Katana 600, and he also has a “Baja” kit for the XR600R. So although Muzzy won’t be working for Honda or Kawasaki on the Nationals this year, he’s still going to figure into the year’s outcome. The only difference is that now he’s working for Rob Muzzy. 0

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsEditorial

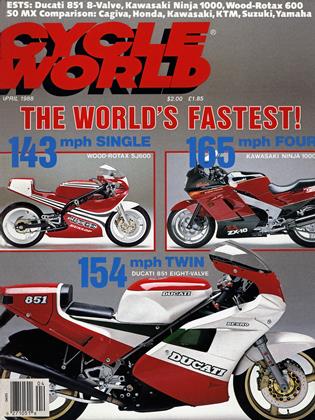

April 1988 By Paul Dean -

Departments

DepartmentsAt Large

April 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

Departments

DepartmentsLeanings

April 1988 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1988 -

Roundup

RoundupYen And the Art of Motorcycle Marketing

April 1988 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

April 1988 By Kengo Yagawa