HONDA SUPER 90, PAST AND PRESENT

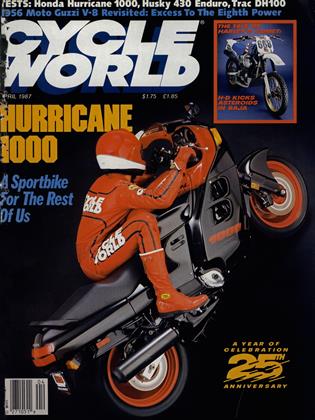

CYCLE WORLD'S 25TH ANNIVERSARY 1962-1987

Resurrecting an old friend

RON LAWSON

THERE’S NO SUCH THING AS an S90 that won't run"’ Paul was saying. There was an undercurrent of skepticism in the room as we all tried to evaluate the truth, or lack thereof, in his statement. This was one of those classic editorial meetings that had drifted away from magazine-related talk and degenerated into a full-on, teary-eyed bull-session. And when the topic is bull, Paul Dean is more than a match for any man alive. “At any rate,” he continued, sensing that his statement needed qualification, “when one won’t run, it doesn’t take much more than a butter knife and a hammer to make it work.”

That was how it all started. It wasn’t that anyone there really disputed what Paul was saying; quite the contrary. We all felt it was a point that had to be proven. And prove it we would. We decided that somewhere, somehow, we had to find an S90—one in any condition, as long as it was complete—and see just how much work it required to run. And, of course, in a process I have never been completely able to follow, the editorial “we” eventually became me.

If it were any other bike, nobody on staff would have cared. But the subject was the Honda Super 90, the one bike that had taught CYCLE WORLD, or at least the majority of the staff’s younger members, to ride. The S90 was the motorcycle on which I had learned the dark and mysterious ways of a manual clutch. It was the first bike owned and raced by CYCLE WORLD’S Western Advertising Manager, Greg Blackwell. It was the first bike owned by Associate Editor Camron Bussard. And it even played a part in the past of some CYCLE WORLD alumni, such as former Feature Editor Peter Egan, now at ROAD & TRACK. The S90 brought back many a tearful memory during that editorial meeting. And in the course of the next two weeks, the S90 would create some new memories that would be tearful for other reasons.

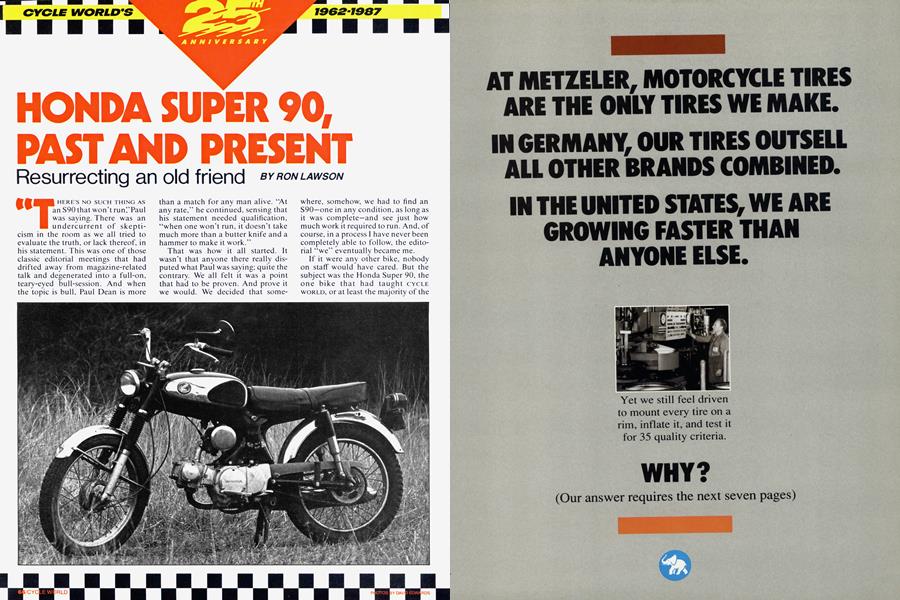

SYD MOVED A BOX OF TAILLIGHT lenses and leaned a CL70 against the wall, sending several small arthropods scurrying away from what had long been a home. After a few more minutes, his digging and shuffling revealed a genuine Honda S90. But this 90 wasn’t like any I remembered from my youth. It had only patches of red paint, broken by large splotches of rust. The seat, or the remnants of the seat, looked like two or three litters of kittens had been delivered on it, and finally became so nasty that no cat would go near it. The carburetor, the front fender, the controls and God knows what else were missing. “Isn’t she something?” asked Syd, the main man at Syd’s Sycle Salvage, who was waiting on me personally. “I was going to restore this puppy myownself. You know, I learned to ride on one of these.”

“I know,” I replied, still finding it difficult to believe that a motorcycle could decompose so completely. “How much?”

“Truth is that I really don’t even want to sell it. I just got a soft spot in my heart for these bikes.” Syd’s heart was about as soft as a lump of coal.

“How much?”

“Two hundred.”

I choked, not believing what I had heard. “Two hundred? Dollars? Are we talking about this motorcycle?”

Syd looked hurt. “Well, hell, I could get $500 just in parts. The engine’s worth $100, and that hub’s worth $80. And look, it’s even got original paint.”

“It doesn’t have any paint. All I brought was $100. I didn’t think I’d need half that.”

My bargaining powers didn’t impress Syd. He made a living by knowing what he could get away with. “I just couldn’t part with her for that.” And with that he dropped the box of taillights back on top of the Honda and walked away, dusting his hands. I left in disbelief.

Two hours later I returned with the required amount of money. Syd smiled. The Honda was mine.

HONDA S90S WEREN’T MUCH, mechanically. An S90 engine consisted of a single overhead cam, a manual clutch that was mounted directly on the end of the crank, and a fourspeed transmission. Honda claimed the bike produced a “notable” eight horsepower at 9500 rpm, and was “capable of speeds up to 65 mph.” What made the Honda so significant wasn’t any technical wizardry, but rather its timing. It was the right motorcycle at the right moment in history. The bike was introduced in 1965, and it sold out so quickly that CYCLE WORLD couldn’t even get one for a test. The price was $370, which made it just about the cheapest “real” motorcycle you could buy. And with the impending motorcycle boom of the late Sixties and early Seventies, the S90 had no choice: It was destined to become the first bike for a generation of new riders.

And, of course, those of us who were in that generation have many fond S90 memories. All of the S90s in CYCLE WORLD’S combined past were purchased used. In 1971, Camron Bussard was able to find one for $100. Greg Blackwell’s father paid $ 100 for his S90, and then ransomed it for good grades. Peter Egan paid $ 180, and although it wasn’t his first bike, it was the first that he could “go places on.” “Places” usually referred to his girlfriend’s house, 60 miles away. “You could actually pass things and not be passed back,” Egan remembers.

The S90 was imported to the U.S. for five years. By the early Seventies, though, it had become too small to satisfy America’s ever-increasing hunger for power. But the machine lived on after that in different forms. The engine that had been designed for the S90 would go on to change the industry when it was placed in a three-wheeler called the US90—the first ATC. And the bike in its original chassis still was popular in other countries well into the Eighties. Today, a restyled S90 is being manufactured by DMC of South Korea, under license from Honda. The Trac DH100, as it’s called, is now returning to the U.S., perhaps to signal the start of a new age in American motorcycling. Or perhaps to start the return of an old age.

TOO MANY PARTS WERE MISSING, too many odds and ends that just couldn’t be found. The resurrection of the 90 was looking doubtful. I ended up going to another salvage yard and getting another partial motorcycle, just for parts.“I had to buy a second one,” I told Paul, who hadn’t really appreciated the bargain I got on the first. “And it only cost $100.” He shook his head and walked away. Expense is a relative thing.

The staff members who were so intrigued by the idea in the first place were now turning on me. Camron and Greg were merciless. “Eve got a really cherry Rambler.” Greg offered.

“Only $ 10,000,” added Cam.

I just kept on working, trading wheels from one to the other, switching front ends. I had a ’67 model and a ’68 model, and I was astonished at how many differences there were. The hubs were different, the side covers on the engines were different, the forks were different. The only thing they really had in common was rust.

But after two days of swapping, I had one complete Super 90 and one pile of parts. Aside from the initial cost of the two bikes, I hadn’t spent a dime on Honda parts. I figured the point would be lost if any new parts were used at all. Besides, most of the kids who work behind parts counters today think an S90 is a generator.

Well, okay, I did have to buy a new battery. And there was some expense incurred in getting the rust out of the fuel tank. But I didn’t use any new mechanical parts, just what had sat at Syd’s for years. And now those parts were assembled in roughly the same shape they had been in 20 years ago, back when Camron, Greg, Peter and I were just entering the world of motorcycling; back when CYCLE WORLD was only five years old, and the S90 was one of the most important motorcycles made.

It didn’t fire with the first kick. Nor with the second or third. There hadn’t been an explosion inside that tiny combustion chamber for ages— the license tag hadn’t even been renewed since 1971. But it did eventually fire up. And it ran.

Memory is a funny thing. Ever go back to a neighborhood you hadn’t visited since childhood? It’s always different. Riding the renewed S90 was a lot like that. It seemed so much larger back then. It seemed so much more powerful then. Riding the bike down Ortega Highway was quite an experience. The bike maxed out around 45 mph, primarily because it was geared much lower than stock. I was in constant fear of being run over by a scooter with a 30 mph closing speed. Cars and trucks were terrifying. The 90’s acceleration was poor. The brakes were worse. And there was mechanical clattering coming from the vicinity of the cam chain. Riding the bike really wasn’t fun at all, nostalgia or no nostalgia. But it did run, and I considered that a major victory. Paul had been right: Making the S90 start had required little more than a butter knife and a hammer. The hardest part was just finding all the parts.

I don’t mean to imply that no Honda Super 90 ever suffered a terminal breakdown. But by and large, they were, and still are, machines that could withstand both time and neglect. They were machines worthy to introduce so many riders to motorcycling.

So, if you ever do run across an S90 that just won’t run, give me a call. I know where’s there’s a good supply of spare parts.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialThe Best of Rides, the Worst of Bikes

April 1987 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeAmerican Style In France And Finland

April 1987 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupLending History A Helping Hand

April 1987 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

April 1987 By Kengo Yagawa -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

April 1987 By Alan Cathcart