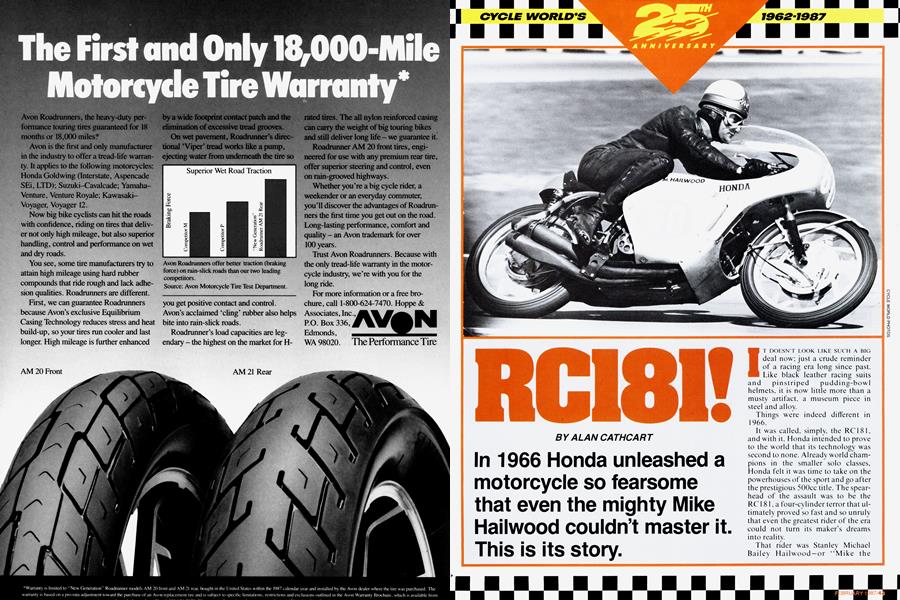

RC181!

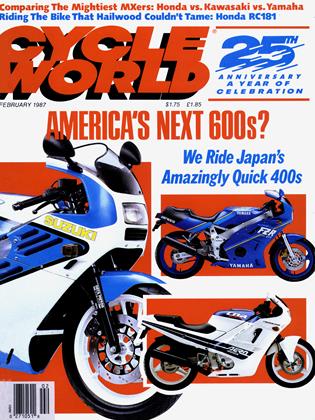

CYCLE WORLD'S 25TH ANNIVERSARY 1962-1987

In 1966 Honda unleashed a motorcycle so fearsome that even the mighty Mike Hailwood couldn’t master it. This is its story.

ALAN CATHCART

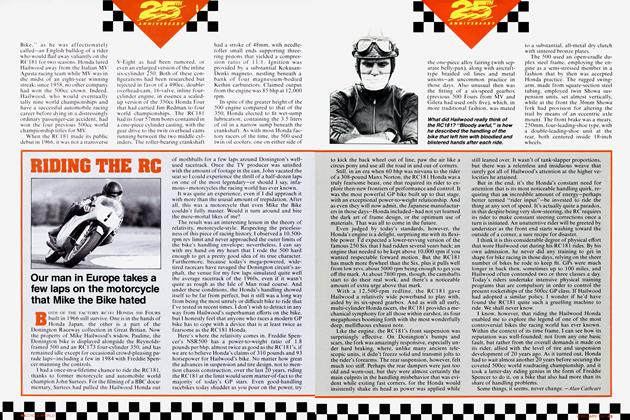

IT DOESN'T LOOK LIKE SUCH A BIG deal now; just a crude reminder of a racing era long since past. Like black leather racing suits and pinstriped pudding-bowl helmets, it is now little more than a musty artifact, a museum piece in steel and alloy. Things were indeed different in 1966. It was called, simply, the RC181, and with it, Honda intended to prove to the world that its technology was second to none. Already world champions in the smaller solo classes, Honda felt it was time to take on the powerhouses of the sport and go after the prestigious 500cc title. The spearhead of the assault was to be the RC181. a four-cylinder terror that ultimately proved so fast and so unruly that even the greatest rider of the era could not turn its maker's dreams into reality. That rider was Stanley Michael Bailey Hailwood—or “Mike the Bike," as he was affectionately called—an English bulldog of a rider who would flail away valiantly on the RC 1 8 1 for two seasons. Honda lured Hailwood away from the Italian MV Agusta racing team while MV was in the midst of an eight-year winning streak: since 1 958. no other company had won the 500cc crown. Indeed, Hailwood, who would eventually tally nine world championships and have a successful automobile racing career before dying in a distressingly ordinary passenger-car accident, had won the four previous 500cc world championship titles for MV

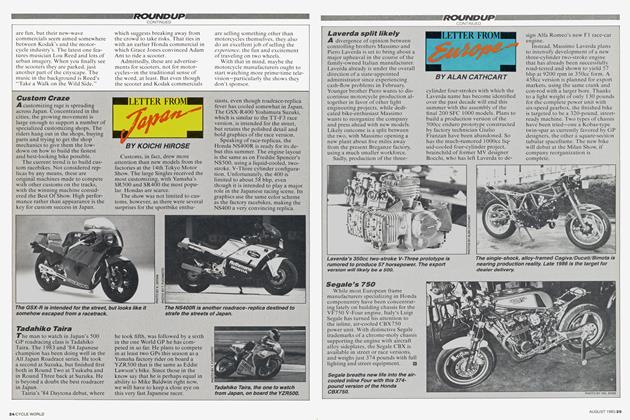

When the RC181 made its public debut in 1 966. it was not a transverse V-Eight as had been rumored, or even an enlarged version of the inline six-cylinder 250. Both of these configurations had been researched but rejected in favor of a 490cc, doubleoverhead-cam, 16-valve, inline fourcylinder engine, in essence a scaledup version of the 350cc Honda Four that had carried Jim Redman to four world championships. The RC181 had its four 57mm bores contained in a one-piece cylinder casting, with the gear drive to the twin overhead cams running between the two middle cylinders. The roller-bearing crankshaft had a stroke of 48mm, with needleroller small ends supporting threering pistons that yielded a compression ratio of 11:1. Ignition was provided by a substantial KokusanDenki magneto, nestling beneath a bank of four magnesium-bodied Keihin carburetors. Claimed output from the engine was 85 bhp at 12,000 rpm.

In spite of the greater height of the 500 engine compared to that of the 350, Honda elected to fit wet-sump lubrication, containing the 3.5 liters of oil in a narrow sump beneath the crankshaft. As with most Honda factory racers of the time, the 500 used twin oil coolers, one on either side of ithe one-piece alloy fairing (with separate belly-pan), along with aircrafttype braided oil lines and metal unions—an uncommon practice in those days. Also unusual then was the fitting of a six-speed gearbox (previous 500 Fours from MV and Gilera had used only five), which, in more traditional fashion, was mated to a substantial, all-metal dry clutch with sintered bronze plates.

The 500 used an open-cradle duplex steel frame, employing the engine as a semi-stressed member in a fashion that by then was accepted Honda practice. The rugged swingarm. made from square-section steel tubing, employed twin Showa suspension units, set almost vertically, while at the front the 36mm Showa fork had provision for altering the trail by means of an eccentric axle mount. The front brake was a meaty, 250mm, four-leading-shoe type, with a double-leading-shoe unit at the rear, both centered inside 18-inch wheels.

In spite of the liberal use of titanium for bolts and fasteners, and even for the wheel axles (a practice since outlawed by the FIM), the RC181 machine scaled a hefty 340 pounds at its debut. With some dedicated work, however, the weight was reduced for 1967 to 310 pounds, thanks largely to the introduction of a revised engine that incorporated many magnesium components.

But that weight reduction was in the future when Redman debuted the RC181 at the German GP at Hockenheim in May of 1966. Hailwood, busy with his 250cc and 350cc rides, did not contest the 500 class that day. Amazingly, Redman won. The 500’s next outing was at Assen in the Dutch TT, where Hailwood had his first race on the bike. He was in scintillating form, leading from the start on the 500 Honda and breaking his own MV lap record by four seconds before selecting a false neutral and falling off while well in the lead. Redman, on the other RC181, initially had been outdistanced by a new MV 420cc Triple ridden by rising Italian star Giacomo Agostini, but sped up and caught Ago on the last lap to score a narrow win. The score was now Honda 2, MV 0.

All was not well beneath the surface, though, for while the RC181’s engine was undoubtedly powerful, its handling was troublesome, to put it politely. “Bloody awful,” was Mike the Bike’s less-genteel assessment of it. Various experiments were conducted with different tire widths,

Redman even trying a skinny, 3.00 x 18 rear Dunlop during practice sessions; but the bike was a real handful at best and terrifying at worst, eating deeply into its ultra-experienced riders’ reserves of skill and bravery.

“It seemed to have a mind of its own when you really tried to take it to the limit,” Hailwood once said. “People used to say that it would use all the road going through a corner, but to me it felt like it was using both sides at once and the curbs as well. I dreaded riding it, to be truthful, but I had a contract which said I had to. And the way I saw it, I had to make the best of it until they could improve it. They just never did. Part of it was a pride thing, too; I didn’t want to get beaten by the MV, which would sort of imply that I’d made the wrong move switching to Honda. If it had been anybody except old Ago on the MV, I might have got away with it; but by then he was pretty damn> good, and though we had some nailbiting races during the two years we raced each other in the 500 class, the Honda really was just too much of a handful to beat him for the championship."

The RC181’s wayward handling could not, however, be blamed for what happened the week after Assen when, after being timed at an incredible 172 mph along the Masta Straight in practice for the Belgian GP at Spa, both Hondas retired from the race with mechanical woes. Hailwood left after leading briefly — he suffering from exposure in the cold, wet conditions, and the RC 1 8 1 sidelined by gearbox problems. Redman aquaplaned off the course and crashed, breaking an arm. Agostini won, giving the new MV its first GP victory, while Redman, perhaps realizing that taming the RC 1 8 1 was not a task he wanted to be involved in any longer, retired from racing then and there, and returned to South Africa.

This left Hailwood in sole charge of the pair of 500 Hondas, with a forlorn chance of catching Agostini for the title. He did his best, of course, but in spite of winning in Czechoslovakia, Ulster and the Isle of Man (each time with the MV in second), his best was not enough. Agostini reversed the finishing order in Finland, where Hailwood was slowed vet

again with gearbox problems. They both failed to finish in East Germany, and in the final race of the year at Monza, with the world championship aready decided in Ago's favor, the Honda again led the race only to rattle to a halt with broken exhaust valves.

Hailwood hoped he'd be able to persuade Honda to radically improve the bike's handling over the winteras he had already done with the sixcylinder 250 on which he had won every GP he contested that season en route to winning both the 250cc and 350cc world titles. But Honda was already scaling down its GP motorcycle-racing efforts, returning for the 1967 season with a team of just two riders, Hailwood and the veteran Ralph Bryans. An increasingly heavy expenditure on FI car racing was the principal reason, as Honda diverted resources from two to four wheels in readiness for its debut in the passenger car market.

Winter development concentrated on upping the power output of the RC l 8 l to 93 bhp at 12,650 rpm. But instead of making the bike more competitive, the added power only made the bike even more of an animal to ride. For instead of producing the much-needed and long-promised new frame. Honda simply beefed up the RCl8Fs existing chassis with a series of ugly, sheet-metal gussets and plates in allegedly strategic places, bringing the weight up without solving the machine’s inherent handling deficiencies.

When he flew to Japan to test the '67-season racebikes, Hailwood was distraught to discover that the promised new chassis had not been developed. But somehow, he persuaded Honda to entrust him with a spare RC l 8 l engine that he brought back home with him so he could commission the building of a chassis that might resolve the problem. The resulting machine, the HRS 500 (Hail wood Racing Special), was manufactured in Italy by Belletti, but designed by Rhodesian Colin Lyster, a friend of Hailwood’s who also experimented with disc brakes on the bike. Though the HRS won both of its first two races (non-championship events at Rimini and Brands Hatch), Hailwood was still forbidden to ride it in a GP as an official Honda factory entry.

Imagine the consternation, then, when Hailwood insisted upon practicing on the HRS for the German GP at Hockenheim, the first GP of l 967—although for the actual race, he reverted to his factory model, which had a revised frame alleged to be 30 percent more rigid than its predecessor. But while leading the event, Hailwood was again put out of action, this time with a broken crankshaft.

Though he was bitterly disappointed at again having to play catchup all year, Hailwood did feel that the new frame was a slight improvement over the old. He wanted to persevere with the Lyster frame, but rumor has it that a cable from Mr. Honda himself expressly forbade this, and so the Italian-built chassis was not seen again.

The next appearance of the RC l 8 l in 1967 was at the Isle of Man TT. where—in a race that has gone down as one of the most exciting ever staged on that island—the two “dear enemies” (as Agostini called Hailwood) swapped the lead back and forth for five of the six laps around the 37.9-mile course until the MV’s chain broke at Windy Corner. Hailwood then cruised to victory, setting an incredible lap record of 108.77 mph, which stood for almost a decade.

At that point, Agostini and Hailwood were equal on points; and after winning at Assen, the Honda took the championship lead. But the very next weekend, the improved MV Three surprised everyone by outpacing the Honda to win the ultrafast Belgian GP at record speed. And the two were equal once again. But at the next round in East Germany, the Honda once more retired with gearbox problems; and in Finland, Hailwood aquaplaned off a soaked track and crashed, although he did counter those DNFs with wins at Ulster and Brno.

Ultimately, the 500 title came to hinge on the crucial GP at Monza. And there, with just three laps to go and a l 6-second lead over Agostini, Hailwood looked finally to have achieved Honda's prized ambition. But then, cruelly, the Honda slowed, stuck in top gear. Ago scorched past to take the checkered flag—and the 500 title for the second consecutive year. A final victory by Hailwood at the last GP of the year in Canada was irrelevant: Honda had lost.

In February of 1968, Honda announced its retirement from GP racing, a decision that would not be rescinded until the debut of the NR500 more than a decade later. Honda did recognize, however, that it was too late in the year for Hailwood to seek alternative employment for the season, so the company sent him a fleet of racebikes, including a 500 Four, with which to contest the lucrative non-championship events in Europe. But by then, Hailwood had had enough of the bucking bronco; he took the spare engine that had been sent with the RC181 and gave it to Ken Sprayson of Reynolds for the construction of a more suitable chassis—ideally, a full-loop affair with inherent torsional rigidity that did not require the engine to act as a stressed member.

The resultant machine took second place in its first-ever race at Rimini in 1968 but never got properly sorted out. And by that time, Hailwood had concluded that his favorite racing bike, the 297cc Honda Six, was not only much more of a crowd pleaser (and hence would bring increased start money) but also more competitive on the tighter circuits on which the non-GP races invariably were run. So after the Brands Hatch race in May of l 968, where he finished fourth in the wet behind a trio of British Singles, Hailwood did not ride the RC181 again; and apart from a couple of outings by fellow Englishman John Cooper, who borrowed the bike at the start of the 1969 season, the RC181 was never again seen in a competitive event.

Instead, the RC181 Honda 500 Four of the l 960s has gone down in history as the stallion which even the legendary Mike the Bike couldn’t completely tame. That being the case, it's doubtful anyone could have.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialSeoul-Searching

February 1987 By Paul Dean -

Letters

LettersLetters

February 1987 -

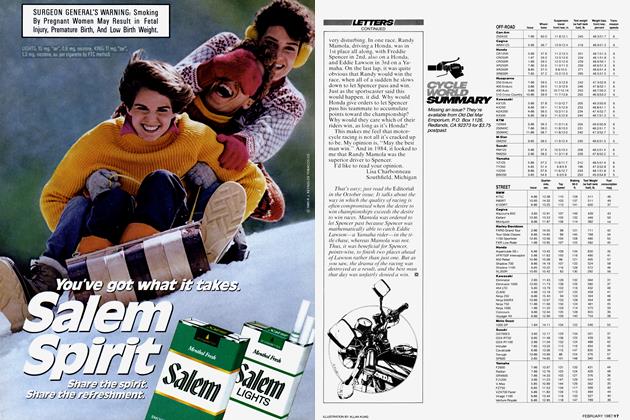

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Summary

February 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupWill Japan's Cure For A Stagnant Market Work In America?

February 1987 By Camron E. Bussard -

Roundup

RoundupWhen School Is Meant To Be A Drag

February 1987 -

Roundup

RoundupHonda's Entry-Level Sportbike: Destined For America?

February 1987 By Koichi Hirose