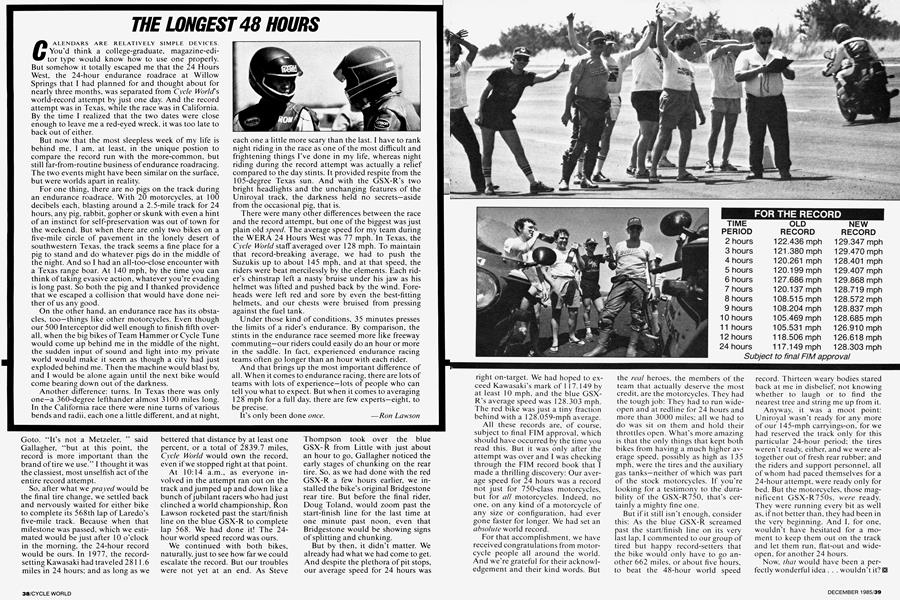

THE LONGEST 48 HOURS

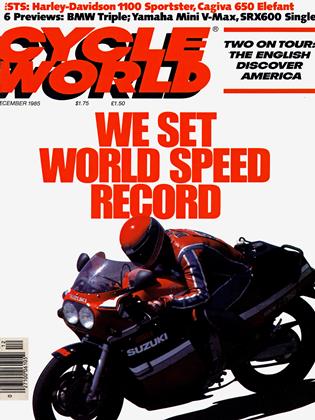

CALENDARS ARE RELATIVELY SIMPLE DEVICES. You’d think a college-graduate, magazine-editor type would know how to use one properly. But somehow it totally escaped me that the 24 Hours West, the 24-hour endurance roadrace at Willow Springs that I had planned for and thought about for nearly three months, was separated from Cycle World's world-record attempt by just one day. And the record attempt was in Texas, while the race was in California. By the time I realized that the two dates were close enough to leave me a red-eyed wreck, it was too late to back out of either.

But now that the most sleepless week of my life is behind me, I am, at least, in the unique postion to compare the record run with the more-common, but still far-from-routine business of endurance roadracing. The two events might have been similar on the surface, but were worlds apart in reality.

For one thing, there are no pigs on the track during an endurance roadrace. With 20 motorcycles, at 100 decibels each, blasting around a 2.5-mile track for 24 hours, any pig, rabbit, gopher or skunk with even a hint of an instinct for self-preservation was out of town for the weekend. But when there are only two bikes on a five-mile circle of pavement in the lonely desert of southwestern Texas, the track seems a fine place for a pig to stand and do whatever pigs do in the middle of the night. And so I had an all-too-close encounter with a Texas range boar. At 140 mph, by the time you can think of taking evasive action, whatever you’re evading is long past. So both the pig and I thanked providence that we escaped a collision that would have done neither of us any good.

On the other hand, an endurance race has its obstacles, too—things like other motorcycles. Even though our 500 Interceptor did well enough to finish fifth overall, when the big bikes of Team Hammer or Cycle Tune would come up behind me in the middle of the night, the sudden input of sound and light into my private world would make it seem as though a city had just exploded behind me. Then the machine would blast by, and I would be alone again until the next bike would come bearing down out of the darkness.

Another difference: turns. In Texas there was only one—a 360-degree lefthander almost 3100 miles long. In the California race there were nine turns of various bends and radii, each one a little different, and at night, each one a little more scary than the last. I have to rank night riding in the race as one of the most difficult and frightening things I’ve done in my life, whereas night riding during the record attempt was actually a relief compared to the day stints. It provided respite from the 105-degree Texas sun. And with the GSX-R’s two bright headlights and the unchanging features of the Uniroyal track, the darkness held no secrets—aside from the occasional pig, that is.

There were many other differences between the race and the record attempt, but one of the biggest was just plain old speed. The average speed for my team during the WERA 24 Hours West was 77 mph. In Texas, the Cycle World staff averaged over 128 mph. To maintain that record-breaking average, we had to push the Suzukis up to about 145 mph, and at that speed, the riders were beat mercilessly by the elements. Each rider’s chinstrap left a nasty bruise under his jaw as his helmet was lifted and pushed back by the wind. Foreheads were left red and sore by even the best-fitting helmets, and our chests were bruised from pressing against the fuel tank.

Under those kind of conditions, 35 minutes presses the limits of a rider’s endurance. By comparison, the stints in the endurance race seemed more like freeway commuting—our riders could easily do an hour or more in the saddle. In fact, experienced endurance racing teams often go longer than an hour with each rider.

And that brings up the most important difference of all. When it comes to endurance racing, there are lots of teams with lots of experience—lots of people who can tell you what to expect. But when it comes to averaging 128 mph for a full day, there are few experts—eight, to be precise.

It’s only been done once.

Ron Lawson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialThe Making of A Record

DECEMBER 1985 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeBattle of the Talking Tees

DECEMBER 1985 By Steven L. Thompson -

Letters

LettersLetters

DECEMBER 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupThe Walkman Cometh

DECEMBER 1985 -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Japan

DECEMBER 1985 By Koichi Hirose -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

DECEMBER 1985 By Alan Cathcart