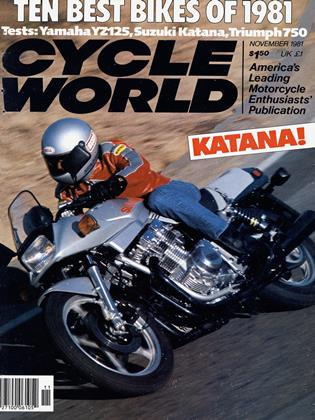

Ten Best Bikes 1981

Choosing the ten best bikes of a model year has never been easy. Fun, controversial and worthwhile, yes, but not easy. Ever since the program began six years ago we’ve had reasoned debates and shouting matches and managed somehow to have the program in order for the October issue.

Right. This is the November issue. We’re a month late and that in itself spells out the model year. New bikes began arriving at the usual time but they didn’t slow down and there were so many new models we couldn’t finish testing in the alloted time.

We think it was worth the wait. Cycle World has been testing motorcycles for nearly 20 years. One of the key elements has been testing each bike on its own. If you're thinking about the Hondaico 250 you want to know all about it, not that it’s lighter or faster than some other bike you’ve never seen.

We have group comparisons, but we can't do many of them each year and fair play means we use the space to report what and how the motorcycles perform, rather than how we feel about them and why.

Because it’s important to us to spell out what we like and what we don’t, there’s the Ten Best. For those who just sat down, the rules are medium clear and occasionally arbitrary.

Some classes are easy. Superbikes are faster than two speeding anything-elses, so the emphasis is on performance. Touring bikes are for going places and feeling as good when you get there are you did when you set out. No displacement rules but naturally big works better than small. Motocross is racing, even though not all motocross bikes appear in formal competition, so the best mxers have to be the ones most likely to win and their classes are based on displacement, just as they are at the track.

Enduro means anything from Sunday foolin’ around to giving Dick Burleson a run for his crown. Dual purpose includes every machine with off-road potential and on-road equipment. Broad, maybe too broad. The other road bikes are divided by engine size mostly because we haven’t been able to come up with a better way; to call one a beginner bike, or a lightweight, is to hint at being not as good as the larger models. Not fair.

Finally, the selections are made by the testing staff, the guys who ride and wrench and even fall off. There are no points tallies. Such devices make no distinction between miles per gallon and ease of choke operation, and even when they’re all fact, the relative importance of load capacity, say, vs. quarter-mile times, is a value judgment better made by the owner than the tester.

So we draw up lists of eligible models, all of which we’ve ridden, and we vote. We argue and explain and sometimes the votes change and sometimes they don't, but when it’s over, we name the best work of the year.

If your bike is here, congratulations. If it's not, well, most of our own bikes didn’t win either.

Superbike: SuzukiGS1100

Superbike history is a series of stages. Once there was just plain performance. Then the factories learned how to build suspensions and brakes to equal their engines, and choosing the best of the road rockets became a delicate equation; balance raw speed against precise handling against the ability of the bike to be used for whatever the rider might want.

The Suzuki GS1 100 solves all that. The GS won its class in 1980, partially because it offered more performance than anything else on wheels, and partially because it offered adjustable suspension that let the rider choose between all day comfort and carving up the canyons.

The other factories noticed and in 1981 there were some worthy rivals. They nicked a few microseconds off the GS’s drag strip times, they handled and they stopped.

The GS is still champion. By some magic of their own Suzuki engineers found a few more bhp lurking in the four-valve Twin-Swirl Four while improving cold starts and low speed throttle response. The suspension was further tuned and some of the unusual trim items, for instance the instrument pod perched above the headlight, have become familiar enough to look better

Added up, the GS1 100 took back the quartermile record for production bikes, gave away little in handling and easily retained the title of best seat in motorcycling.

That makes it Best Superbike.

Open Motocross: SuzukiRM465

Open class motocross was a surprise beneficiary of long-travel suspension. Time was the 400s and 501s were more badge of courage than ticket to the winner's circle and the prizes went to the 370s, which didn't have more power than they could use.

But strong front ends, flex-free frames, one useful foot of wheel travel and sophisticated single rear shocks changed that and you’ll need more than one hand before you’ve tallied the competitive 450-plus motocross machines.

The RM465 is the best of the crop. Why begins with the basic design. Suzuki made a 250 with the bulk of a 1 25, and followed with a 465 that’s sized like a 250. The RM is a few pounds lighter and an inch or so shorter than its rivals, so it’s less tiring to ride and easier to turn.

Power isn’t so much adequate as it is different. When our test 465 arrived it burbled and then went off like a rocket. Uh oh, we said, another open class catapult. Not quite. With the right jets and the timing backed off the RM had just enough power at every engine speed.

There are good little items like straight-pull spokes and a giant eight-petal reed cage and the best brakes in motocross and beefy front forks and the rear suspension, Suzuki’s Full-Floater, is simply the best there is.

Balance is the word here. The RM465 needs some attention, but tuned right and ridden right, it can whip anything else on knobby tires.

Touring: HondaGL1100 Interstate

Touring bikes, like the other subject the Supreme Court justice had in mind, defy description but we all know them w'hen we see them.

Honda saw them years ago, and figured the longhaul public would appreciate a big, quiet engine with extras like water cooling and shaft drive. So they introduced the Gold Wing and while people scoffed about two-wheeled cars, they also bought GLs by the thousands.

And added extras like fairings and saddlebags and top boxes and radios and extra lights, all of which were made by outside suppliers.

Honda took the next step and offered the Interstate package. Fairing, saddlebags, top box, airassisted suspension, a seat that can be adjusted fore and aft, even a signal-seeking radio.

We took a fleet of factory-packaged touring bikes out for a comparison journey last year, so when Ten Best time rolled around the choice was easy. The Gold Wing did everything well, and while it wasn’t the fastest or the most nimble or the most economical, the GL was the bike most likely to be grabbed when it came time to see what was on the other side of the mountain.

Once again the competition hasn't sat still and the accessory companies have come out with different and better equipmeni.

But we haven’t seen anything better than the GL-I when it comes to rolling out of the showroom and pointing the front wheel toward the other coast.

Enduro: YamahaIT465

Enduro, as they say in Wonderland, means anything you want it to mean. For the brushbuster and mudhole set it's a bike that can win real enduros. For Sunday cowtrailers and kids in sandlots, it’s something else and the factories work hard to make sure there’s a good machine for every different usage.

II they all do most of what they’re supposed to do, how can we distinguish among the best ones in various groups?

This year it’s a mix of excellence and new.

The IT465 comes with a displacement made famous earlier by its cousin, the YZ 465. Wrhen the motocrosser hit the tracks strong men averted their eyes. Here, for the first time, was a motocrosser with more power than the open class pros could use, and it had brakes to match.

But for 1981 Yamaha arrived with a re-tuned IT version of the YZ motor, in basically the motocross frame and suddenly there was a big IT that worked, turned and handled.

If there was any loss in top end when the 465 was given tractor power on the bottom and in the middle, we never missed it. Wide open the IT465 is fast enough to ripple your Moto-lII. Ticking along the IT will slog through swamps. In between, there’s this killer hill we know. Not even the thumping four-strokes can top it.

So we got the IT465 and up she went, in 2nd.

As they say in boxing, if it’s a good big boxer against a good small boxer, bet on the big one.

651-800cc Street: KawasakiKZ750

Five years ago Kawasaki sprang a surprise.

Their performance bike was the mighty 900, which meant their 750 was a sturdy Twin. To fill the mid-range gap they brought out a 650 Four that the ads said would beat the 750s. And it would have, except the other chaps brought out quicker 750s.

Lesson learned. The 900 became the 1000 and was joined by the 1100, while the home-market 500 Four was enlarged to 550, and raised to a sporting stage of tune.

Then came the 750 Four and the claim comes true. The KZ750 is the quickest 750 on the market.

The 750 class has become a challenge, as all four of the majors offers an inline, transverse, dohc Four and each has a character and flavor more distinct than the specifications show.

We rode them all this year, in group, and liked them all, each for its own reasons. During the test and after we were asked and asked each other, which will win? and which would you buy?

The Kawasaki.

Why? Because a 750 should be smaller and lighter than a 1000. It should offer agility and ease of operation while still having room for two people and a cross-country-capacity fuel tank. If along with that it’s also the quickest and cleanest in design, why, you’ve got the 750 that best does what 750s should do.

And you’ve got the KZ750.

Dual Purpose: SuzukiSP500

Once a thriving class, dual-purpose motorcycles have lost some of their sparkle during the past few years and that’s odd. The earlier versions weren’t nearly as good as the current crop, but as the dirt bikes became better in the dirt, and road bikes better on the road, motorcycles designed to do both haven’t been popular for either.

In continuing to improve their four-stroke SP Single, Suzuki has gone against the trend. They deserve the thanks of those willing not to listen to people who say a bike can’t work in either world.

For 1981 the SP500 grew from the 400 and earlier 370, and with the increased displacement came a single overhead cam version of the fourvalve Twin-Swirl design and dual counter-balancers, plus a clever kick-start device that lets the rider ease the engine into the proper position.

The SP looks right, with the peaked tank, generous plastic fenders, low bars and square seat first seen in motocross, and while weight is average for type and displacement, the extras justify the pounds.

One of the staff commuted on the SP, his normal 90 mi. a day and he reported that he could keep up with the traffic when it raced along and nip through the mess when it didn’t. Gee, he said, for a dirt bike this thing is nice on the highway.

One of the desert racers spent weekends blasting up sand washes and across rocks and logs. Don’t count on a Gold Medal, he exclaimed, but for a road bike this works great in the dirt.

451-650cc Street: KawasakiGPz550

Now here’s a repeat winner with a difference. In 1980 the middleweight champion was the KZ550, the expanded home market 500cc Four that put fun back into less-than-monster Multis. Kawasaki wasn’t the only factory with this laudable aim and for 1981 another 550 Four arrived in cafe-racer clothes.

But the KZ550 had become the GPz550. The engineers fitted hotter camshafts, raised the compression ratio to 10:1 and revised the ports, exhaust, jets, etc. so the 550 kept its mid-range punch and set a new 550 record of 12.65 sec. with a trap speed of 104.16 mph. Better than the other 550s, nearly as quick as the legendary 900cc Z-l. At the same time the final drive ratio was changed to give more relaxed cruising and all this—more power, more speed, at lower revs per mile—dropped the mpg from 63 to 62.3. Amazing.

With its red paint and black stripes, the useful little fairing, semi-rearset pegs and generous, flat tank, the GPz looks the part of production racer. It should; the Kawasaki has done very well in club races.

It would have been nice if the engine was a bit less touchy about the choke setting when cold and we don’t see why the factory couldn’t have included a balance tube for the air-assisted forks, but the price is reasonable and that’s probably how they kept it so. The GPz550 has the traditional Kawasaki hot-rod feel, without the raw edges.

250cc Motocross: SuzukiRM250

One surefire recipe for success in racing is to assemble all the best pieces . . . and then add lightness.

Suzuki has been reading the book. The usual way a 250 motocrosser goes together is to share components, i.e. frame, suspension, etc., and install either a 250 engine or a 400 and beyond engine. Big engines produce more speed and stress and because the shared parts must handle the big motor, the 250 is stronger (good, maybe) and heavier (bad, always) than it could have been.

But when Suzuki designed the RM250, parts came from both directions as it were, with bits from the 125 as well as the 465. As a result the RM with half a tank of fuel weighs 225 lb., 20 lb. less than the water-cooled Honda and 8 lb. less than the Yamaha YZ250.

The RM250 engine is new for 1981 and it’s nicely compact.

The 250 (and the 465) sparkle with neat ideas. The wheel spokes are straight pull and not one worked loose during weeks of racing. The brake shoes are centered in the hub and because they’re large and the linkage ratios are right, they work even better than the dual leading shoes found on rival bikes.

It doesn’t have the most power in class. Where it wins is going through the whoops and out of turns. At the races the RM gains one length or two every corner. Power on the ground beats wheelspin and the RM250 beats the others.

Under 450cc Street: SuzukiGS450S

Beginner bike. Even the name sounds dreadful, bearing as it does visions of underpowered tiddlers struggling beneath the burden of awkward novices. We all had to begin somewhere but even so, who wants to look like a beginner and who wants a beginner bike?

The problem is part of the small street class. Other things being equal the Singles and Twins of less than 450cc are best for new riders. Because they do that well they’ve come to have the stigma of being not quite good enough for anything else, of being bikes you outgrow.

Not so the Suzuki GS450S. The “S” stands for sport and the 450S comes with low bars, small fairing and large fuel tank.

The 450S is as economical as most of its rivals, allowing for exceptions like 125 Singles, while being the quickest of the 400cc Twins and having as much speed and acceleration as more than a few 500s and even a couple of 650s.

The 450S isn’t perfect. On the track the forks lack that final degree of control. As delivered to the owner the carbs are one click too lean at low revs, something that can be easily fixed by the owner but not—by federal statute—by the dealer.

Never mind. The GS450S thrives on the open road. It’s comfortable enough and big enough to be as good when you know how to ride as it was when it helped you learn.

125cc Motocross: SuzukiRM125

Water cooling and single rear shocks are the news in the 125 motocross class this year, but because the 125s from each of the big four have solo shocks, and three come with radiators, the battle must be settled on things other than merely new.

Suzuki’s RM 125 is new, however. The watercooled engine shares almost no pieces with the earlier versions and the frame needed so many changes to work with the Full-Floating rear shock that they went ahead and redid everything there.

What’s best begins with the extras, like the power. We raced the RM at various tracks and against some good machines and never lost the race to the first turn. Sure, you have to fan the clutch some, just like any tuned 125, but there was enough power for even the big guys.

Steering is precise and the rider can put the RM where he likes, but the best part of the handling comes from the rear suspension. Single shock, as are they all. Rising rate, which is the coming thing in motocross and for the street.

The Full-Floater—so named because there are links at both ends of the shock—is the last to arrive and the time was well spent. It can be adjusted for damping and spring preload, it doesn’t sag or top or pitch the rider ... it works. None of our riders could pinpoint why, but the Full-Floater was the easiest to ride and did the best over the widest variety or terrain for the widest range of rider weight and skill.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsUp Front

November 1981 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1981 -

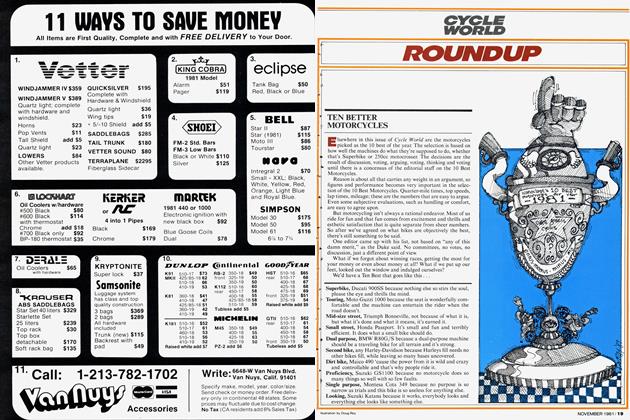

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

November 1981 -

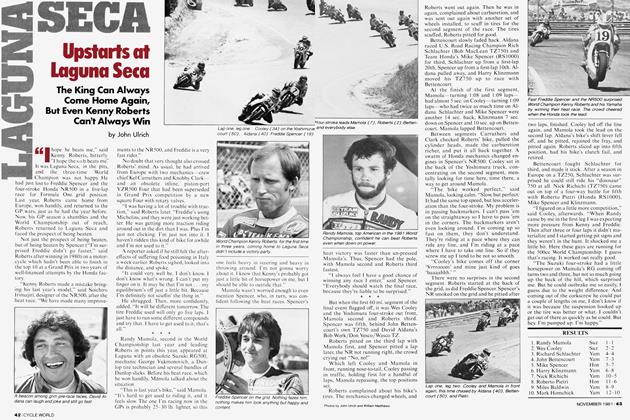

Laguna Seca

Laguna SecaUpstarts At Laguna Seca

November 1981 By John Ulrich -

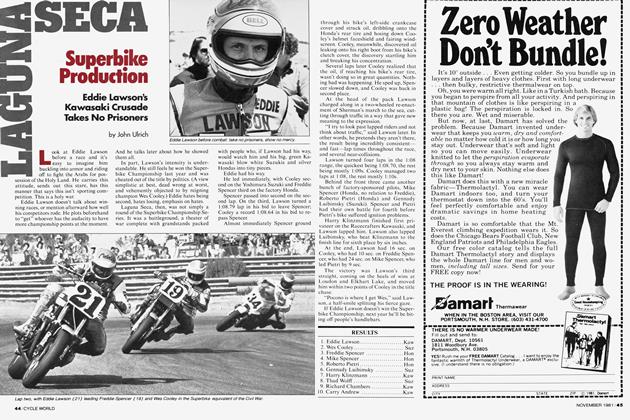

Superbike Production

November 1981 By John Ulrich -

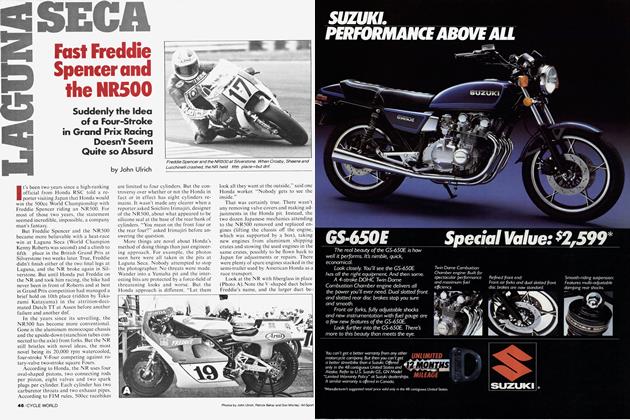

Fast Freddie Spencer And the Nr500

November 1981 By John Ulrich