Fast Freddie Spencer and the NR500

Suddenly the Idea of a Four-Stroke in Grand Prix Racing Doesn’t Seem Quite so Absurd

John Ulrich

It’s been two years since a high-ranking official from Honda RSC told a reporter visiting Japan that Honda would win the 500cc World Championship with Freddie Spencer riding an NR500. For most of those two years, the statement seemed incredible, impossible, a company man’s fantasy.

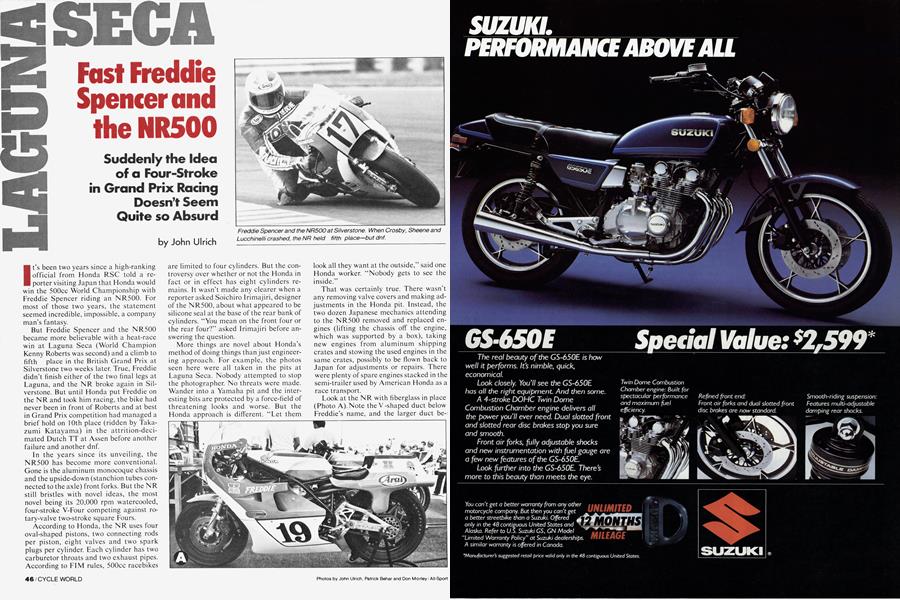

But Freddie Spencer and the NR500 became more believable with a heat-race win at Laguna Seca (World Champion Kenny Roberts was second) and a climb to fifth place in the British Grand Prix at Silverstone two weeks later. True, Freddie didn’t finish either of the two final legs at Laguna, and the NR broke again in Silverstone. But until Honda put Freddie on the NR and took him racing, the bike had never been in front of Roberts and at best in Grand Prix competition had managed a brief hold on 10th place (ridden by Takazumi Katayama) in the attrition-decimated Dutch TT at Assen before another failure and another dnf.

In the years since its unveiling, the NR500 has become more conventional. Gone is the aluminum monocoque chassis and the upside-down (stanchion tubes connected to the axle) front forks. But the NR still bristles with novel ideas, the most novel being its 20,000 rpm watercooled, four-stroke V-Four competing against rotary-valve two-stroke square Fours.

According to Honda, the NR uses four oval-shaped pistons, two connecting rods per piston, eight valves and two spark plugs per cylinder. Each cylinder has two carburetor throats and two exhaust pipes. According to FIM rules, 500cc racebikes are limited to four cylinders. But the controversy over whether or not the Honda in fact or in effect has eight cylinders remains. It wasn’t made any clearer when a reporter asked Soichiro Irimajiri, designer of the NR500, about what appeared to be silicone seal at the base of the rear bank of cylinders. “You mean on the front four or the rear four?” asked Irimajiri before answering the question.

More things are novel about Honda’s method of doing things than just engineering approach. For example, the photos seen here were all taken in the pits at Laguna Seca. Nobody attempted to stop the photographer. No threats were made. Wander into a Yamaha pit and the interesting bits are protected by a force-field of threatening looks and worse. But the Honda approach is different. “Let them look all they want at the outside,” said one Honda worker. “Nobody gets to see the inside.”

That was certainly true. There wasn’t any removing valve covers and making adjustments in the Honda pit. Instead, the two dozen Japanese mechanics attending to the NR500 removed and replaced engines (lifting the chassis off the engine, which was supported by a box), taking new engines from aluminum shipping crates and stowing the used engines in the same crates, possibly to be flown back to Japan for adjustments or repairs. There were plenty of spare engines stacked in the semi-trailer used by American Honda as a race transport.

Look at the NR with fiberglass in place (Photo A). Note the V -shaped duct below Freddie’s name, and the larger duct be-hind it. The forward duct supplies cold air to the carburetors, via an enclosed tunnel. Hot air from the radiator is ducted away from the carbs, around the cold-air-intake tunnel and out the larger, rearward duct. The incoming cold air is not rammed into the carbs,but is simply fed into the general vicinity of the velocity stacks, which are shielded from hot radiator air by plastic ducting.

The four exhaust pipes from the rear bank of cylinders wind around the single rear shock absorber and terminate in a muffler running underneath the seat/tail section

fiberglass.

Photo B shows the right side of another NR500 in the Laguna pits (there were two, nearly identical machines). The exhaust pipes from the forward bank of cylinders end in a muffler running alongside the swing arm.

Photo C is a close up of the front wheel and forks. Note the externally-routed damping circuit on the forks. Also note the pivot above the brake caliper and the spring-loaded mechanical linkage below the caliper. The NR has a mechanicallyoperated anti-dive. When the brakes are applied, the caliper grips the disc and is pulled forward, the linkage below pushing a needle valve against a seat to restrict compression damping oil flow. How much oil flow is restricted is adjustable by turning a screw in fittings (seen on the leading edge of the fork tubes) located at either end of the external oil passageway. The fittings click into different positions, with a very small range of adjustment.

The four-piston caliper uses differentsized pistons. The lower piston on each side of the caliper must be smaller to accommodate the caliper’s pivoting action. If the piston (and the pad it activates) was not smaller, it would pivot off the braking surface of the disc.

The caliper bolts together, with an external line carrying fluid from one side to the other to reduce the likelihood of leaks at the joining surface.

Photo D shows the NR’s engine and dual-throat, dual-float magnesium carburetors. The forward carbs have float bowls positioned off to the side for a more compact fit. The rear cylinder bank has silicone seal smeared at the base to plug an oil leak, while the rest of the engine is sprayed with a dry, white pow'der to pinpoint developing leaks.

The NR has a very short stroke, as seen by the tiny distance between the cylinder head and the crankcases.

Judging from the routing of the exhaust header pipes, trying to keep pipe lengths equal may be impossible, the designers perhaps having to take any routing they can get. Perhaps adjustments in individual cylinder intake ports compensate for the involved exhaust plumbing.

Photo E shows the four spark plugs used to light the forward cylinders, with an aluminum oil cooler mounted in front of the exhaust header pipes. Note head pipe routing beneath the engine, and the space between pipes and engine. The pipes leading to the radiator are giant. A close look at the lower triple clamp on the front end shows welded, built-up construction, possibly out of aluminum plate. Fork stanchion tubes are beefy, possibly 40mm, and the triple clamps have little offset. The NR500 has a very steep rake angle and lots of trail, the steep rake making the bike quick steering and the trail adding stability.

Once out of the frame (Photo F) the NR powerplant looks massive—and is, compared to the two-strokes it races against. Even the extensive use of magnesium in engine castings and titanium for fasteners and some engine parts (such as valves) can’t make the NR as light as its competitors. Viewed here, the frame is conventional, the front section resembling a KR250 Kawasaki.

Beefy NR500 aluminum swing arm (Photo G) doesn’t look likely to flex. Single Showa shock mounts at the bottom to Pro-Link linkage and at top to an aluminum plate bolted to gussets welded to the upper rear frame rails. One-piece rear disc/disc carrier on this bike is aluminum with plasma sprayed on the working surface, but during one practice session the bike was fitted with a carbon-fiber disc and carbon-fiber pads to match. Various hanger plates visible in this photo are magnesium, all hardware titanium. A look at the magnesium shift lever and the titanium rear caliper stay arm offers a study in how to make parts lighter. Wheels are magnesium ComStars with titanium fasteners. Small tank ahead of rear master cylinder remote reservoir is crankcase catch tank.

Listening to the NR500 on the track, it doesn’t really sound like a four-stroke or a two-stroke. What’s it like to ride it? “It’s not exactly either one,” said Freddie after the heat race. “It feels like a two-stroke but has the characteristics of a fourstroke, like engine braking.

“Before I rode it I thought ‘Man, this thing turns 20,000 rpm, it’s got to be really strange to ride, really hard to ride.’ But it’s not. It turns all that rpm but the only way you know it is by the tach. It doesn’t really feel like it’s turning that much rpm. You look at the tach and the powerband is pretty wide. But maximum power, where I have to keep it to use all the power it’s got, is from about 18,500 to 20,000. That’s the hardest thing about riding it, keeping it in the narrow actual maximum power band. It doesn’t really pull good before 18,500. It’s only a 500, and it is a four-stroke, and it just doesn’t have the acceleration the two-strokes have.

“It handles good. Especially compared to our bigger, lOOOcc four-strokes, it’s light and brakes so well. I’ve ridden a production Suzuki (RG500) and a production Yamaha (TZ500) and it handles better than them. I haven’t ridden another factory bike so I don’t know how it compares. It’s the best-handling bike that I’ve ridden. The NR500 really feels good and it has a 16-inch front wheel so it really turns well. The 16-inch front wheel makes it flick so much easier, like through the turns it’s a lot better than an 18-inch wheel.”

If anybody can make a four-stroke win a 500cc World Championship, it is Honda. If anybody can ride a Honda to a 500cc World Championship, it’s Freddie Spencer. We don’t know how the NR500 and Fast Freddie will fare in the 1982 Grands Prix. But we do wish them luck.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsUp Front

November 1981 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1981 -

Departments

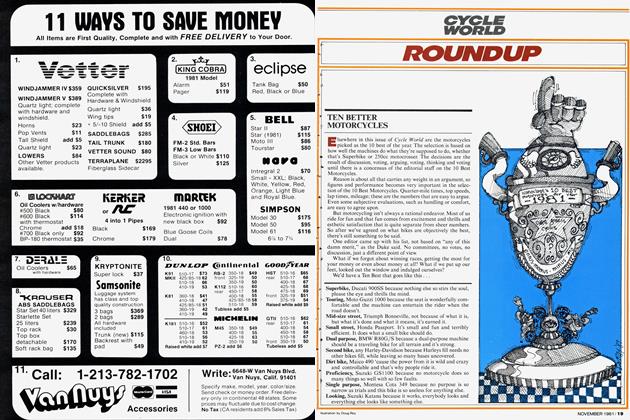

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

November 1981 -

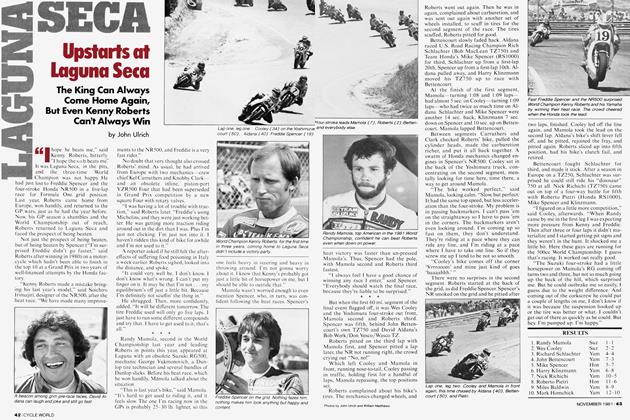

Laguna Seca

Laguna SecaUpstarts At Laguna Seca

November 1981 By John Ulrich -

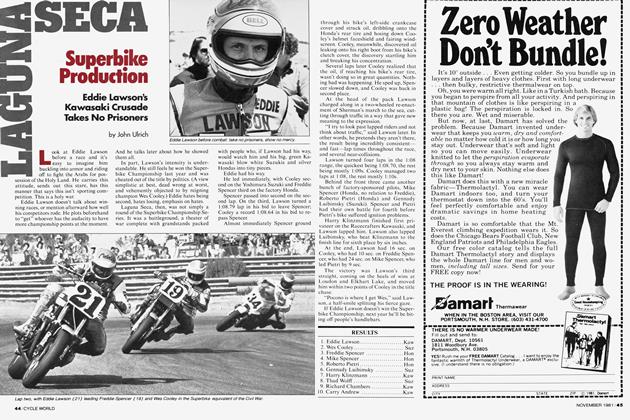

Superbike Production

November 1981 By John Ulrich -

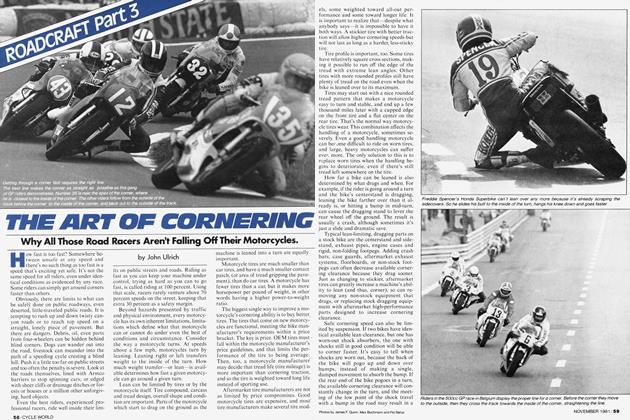

Feature

FeatureRoadcraft Part 3 the Art of Cornering

November 1981 By John Ulrich