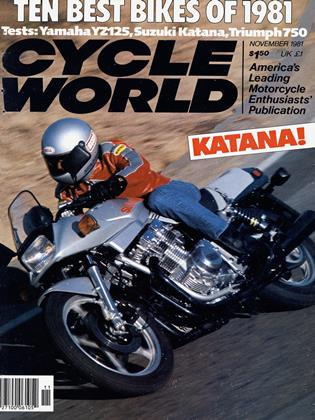

ROADCRAFT Part 3 THE ART OF CORNERING

Why All Those Road Racers Aren't Falling Off Their Motorcycles.

John Ulrich

How fast is too fast? Somewhere between unsafe at any speed and there’s no such thing as too fast is a speed that’s exciting yet safe. It’s not the same speed for all riders, even under identical conditions as evidenced by any race. Some riders can simply get around corners faster than others.

Obviously, there are limits to what can be safely done on public roadways, even deserted, little-traveled public roads. It is tempting to rush up and down twisty canyon roads or to reach top speed on a straight, lonely piece of pavement. But there are dangers. Debris, oil, even parts from four-wheelers can be hidden behind blind corners. Dogs can wander out into the road, livestock can meander into the path of a speeding cycle cresting a blind hill. Push it a little too far on public streets and too often the penalty is severe. Look at the roads themselves, lined with Armco barriers to stop spinning cars; or edged with sheer cliffs or drainage ditches or forests or houses or a million other unforgiving, hard objects.

Even the best riders, experienced professional racers, ride well inside their limits on public streets and roads. Riding as fast as you can keep your machine under control, trying as hard as you can to go fast, is called riding at 100 percent. Using that scale, racers rarely venture above 70 percent speeds on the street, keeping that extra 30 percent as a safety margin.

Beyond hazards presented by traffic and physical environment, every motorcycle has its own inherent limitations, limitations which define what that motorcycle can or cannot do under even the best of conditions and circumstance. Consider the way a motorcycle turns. At speeds above a few mph, motorcycles turn by leaning. Leaning right or left transfers weight to the inside of the turn. How much weight transfer—or lean—is available determines how fast a given motorcycle can go around a given turn.

Lean can be limited by tires or by the motorcycle itself. Tire compound, carcass and tread design, overall shape and condition are important. Parts of the motorcycle which start to drag on the ground as the machine is leaned into a turn are equally important.

Motorcycle tires are much smaller than car tires, and have a much smaller contact patch, (or area of tread gripping the pavement), than do car tires. A motorcycle has fewer tires than a car, but it makes more horsepower per pound of weight, in other words having a higher power-to-weight ratio.

The biggest single way to improve a motorcycle’s cornering ability is to buy better, tires. The tires that come on new motorcycles are functional, meeting the bike manufacturer’s requirements within a price bracket. The key is price. OEM tires mustfall within the motorcycle manufacturer’s price guidelines, and that limits the performance of the tire to being average. Then, too, a motorcycle manufacturer may decide that tread life (tire mileage) is more important than cornering traction, and so the tire is weighted toward long life. instead of sporting use.

Aftermarket tire manufacturers are not as limited by price compromises. Good motorcycle tires are expensive, and most tire manufacturers make several tire models, some weighted toward all-out performance and some toward longer life. It is important to realize that—despite what anybody says—it is impossible to have it both ways. A stickier tire with better traction will allow higher cornering speeds but will not last as long as a harder, less-sticky tire.

Tire profile is important, too. Some tires have relatively square cross sections, making it possible to run off the edge of the tread with extreme lean angles. Other tires with more rounded profiles still have plenty of tread on the road even when the bike is leaned over to its maximum.

Tires may start out with a nice rounded tread pattern that makes a motorcycle easy to turn and stable, and end up a few thousand miles later with a cupped edge on the front tire and a flat center on the rear tire. That’s the normal way motorcycle tires wear. This combination affects the handling of a motorcycle, sometimes severely. Even a good handling motorcycle can become difficult to ride on worn tires, and large, heavy motorcycles can suffer ever; more. The only solution to this is to replace worn tires when the handling begins to deteriorate, even if there’s still tread left somewhere on the tire.

How far a bike can be leaned is also determined by what drags and when. For example, if the rider is going around a turn and the bike’s centerstand is dragging, leaning the bike farther over than it already is, or hitting a bump in mid-turn, can cause the dragging stand to lever the rear wheel off the ground. The result is usually a crash, although sometimes it’s just a slide and dramatic save.

Typical lean-limiting, dragging parts on a stock bike are the centerstand and sidestand, exhaust pipes, engine cases and rigid, non-folding footpegs. Adding crash bars, case guards, aftermarket exhaust systems, floorboards, or non-stock footpegs can often decrease available cornering clearance because they drag sooner. Just as changing to stickier, aftermarket tires can greatly increase a machine’s ability to lean (and thus, corner), so can removing any non-stock equipment that drags, or replacing stock dragging equipment with aftermarket high-performance parts designed to increase cornering clearance.

Safe cornering speed can also be limited by suspension. If two bikes have identical available lean clearance, but one has worn-out shock absorbers, the one with shocks still in good condition will be able to corner faster. It’s easy to tell when shocks are worn out, because the back of the bike will pogo up and down over bumps, instead of making a single, damped movement to absorb the bump. If the rear end of the bike pogoes in a turn, the available cornering clearance will constantly change in the turn, and the meeting of the low point of the shock travel with a bump in the road may result in a slide or crash as a solid part of the bike grounds out.

The theory of fast riding comes from road racing, organized competition on paved, closed-circuit racetracks. The point is to make it around the racetrack in the shortest possible time, or lap time, which requires traveling at the greatest possible speed at all times.

Motorcycles can travel fastest when traveling in a straight line, and the way to get a motorcycle through a section of curves quickly is to make the curves as “straight" as possible.

Imagine a 90° right turn. A typical motorist drives up to the turn, turns right, and goes on his way. The motorist’s path looks like an upside-down “L.”

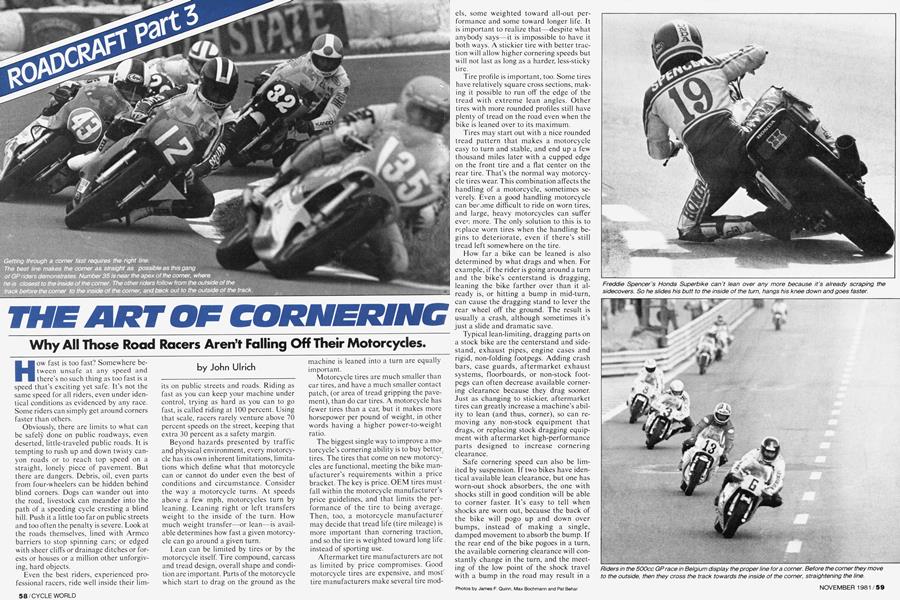

The fast way through that turn is to start at the extreme left-hand edge of the pavement, peel off in an arc headed for an apex at the inside edge of the turn, and continue past the apex to the outside edge of the pavement beyond the turn. Instead of an L, the path of the motorcycle looks like half a set of parentheses.

Using this theory, a set of left-right-left turns, or S-turns, can be ridden fastest by taking an almost-straight line clipping the turn apexes. Instead of a meandering, leftright-left path through the turns, the fast way is right up the middle.

It sounds simple, and to those who do it all the time, it is simple. Learning it isn’t that simple.

Take for example the man who read a motorcycle magazine regularly, soaked up all he could about riding fast, went out on a lonely road and tried to ride fast all at once.

He crashed, and wrote to the magazine wondering how those guys in the magazine lean those bikes over so far without crashing.

The key is experience, and starting out slow and working up to it. Before a rider can safely fly down a piece of curvy pavement, he’s got to learn to recognize, interpret and deal with the warning signals that motorcycles give their pilots, warning signals that mean the bike and rider have reached their limits.

The way to find a bike’s limits is to start out at a safe speed and increase speed through the same corner increments at a time. Using the same corner eliminates other variables that may confuse the issue. Increasing speed a bit at a time gives the rider that chance to find the limits before crashing. Note anything the bike does differently on any given pass through the corner. Get off after the pass, and look for scrape marks on the footpegs, the pipes, the stands.

Footpegs often scrape first, and as long as they are non-rigid, folding-type pegs (usually spring-loaded), scraping them isn’t dangerous. But once the pegs are dragging, care must be taken as the next thing that drags is discovered. That next thing is likely to be very hard, very rigid and very non-folding, all invitations to trouble.

Depending upon where the scraping item is located, it may or may not be safe to drag consistently. For example, if part of the centerstand drags, it will usually lift the rear wheel if ignored, and as long as the wheel doesn’t get completely off the ground, the rider can feel the rear end start to slide and correct by slowing slightly and steering into the slide, then carrying on.

But on some bikes, the exhaust system drags near the front of the frame, often lifting the front wheel. It’s usually impossible to save a front-wheel slide, and the result is a very quick crash.

Often great improvements in cornering clearance can be had by removing offending, scraping items, especially centerstands.

Suspension settings can affect available cornering clearance. A bike with the rear shock springs set at maximum preload will have a higher ride height than when the shock springs are set at minimum preload. That means that the bike can be leaned over farther before hard things start to drag. The trouble is, the stiffer rear suspension may not react enough to small bumps and road irregularities, causing the rear tire to slide when it hits such bumps.

The key is to hit a happy medium between no ground clearance and sliding tires. After-market shock absorbers and better tires often help a rider reach that medium, and make a bike safer to ride around corners faster. But still, every bike has its limits, even if those limits are raised.

How does a rider detect a tire sliding? The extreme case is when the rear end of the bike swings to the side, putting the bike almost sideways in the turn. That can happen from ignoring the warning signals that the rear tire has been pushed too far or that something hard is dragging on the ground.

Experience is the key. You’ve got to experience tires sliding before you can detect a slide starting at the beginning, before it gets out of hand. Different tires have different slide characteristics. Cheap tires with hard rubber compounds may give the rider almost no warning of an imminent slide, breaking traction all at once and putting the bike sideways. Other tires give plenty of warning with a controlled, steady sideslip that is easily caught and corrected.

Getting experience is best done at a racetrack where there are no cars coming the opposite direction, where the track surface is relatively good and where you will be required to wear protective clothing. Road racing clubs around the country offer road racing schools, usually the day before race day. In these schools experienced road racers will explain how to ride on the track, they will lead new riders around the track and they will follow the new riders around, making suggestions on how to improve. These schools generally cost nothing but the cost of practicing on the track. Even riders who might not want to compete in races can benefit from the schools. One outfit, the California Superbike School, has a highly organized program of learning to ride fast. The school conducts classes at mostly California race tracks, but has held sessions at Daytona Beach during the week of the Daytona 200. Motorcycles, leathers, helmets, boots and all necessary equipment is provided.

While at the racetrack for a club race, look at more than just the winner and the pit tootsies. Look at the bikes. Box stock classes require the bikes to be street legal, so notice what brands of tires are used by the successful racers. And what other equipment is being used. That’s a good clue of what works at that track.

An important reminder for anybody intent on riding fast on public roads: Riding at 100 percent, racers use all the racetrack in their path through a corner. It is very important when riding on the street to not only not ride at 100 percent, but also to not use all the road. You may need an extra two feet on either side to avoid something you won’t see until you’re in mid turn. Racetracks have everyone traveling in the same direction and have turn workers watching for oil and debris or animals, and riders are signalled at turn entrances if there’s trouble ahead. Public roads have no such features, and come complete with drunken drivers, cars on your side of the road, and police.

Once you’ve learned how to detect and deal with the limits of your bike and tires, you’re ready to work around those limits. Remember, leaning is just a method of transferring weight to the inside as you hurtle through a corner. The farther you can lean, the more weight you transfer and the faster you can go through the corner.

So you’ve worked up to 50 mph through a tight turn with a perfect line and the bike skimming the exhaust system along the pavement all the way.

‘ The way to go faster through the corner is to get more weight transfer without more lean. It’s called hanging off, and it involves sliding your body off the seat toward the inside of the turn. To start with, try sticking your knee straight out toward the inside of the turn. That’s a little weight transfer. See if the additional weight transfer helps. Be sure to make your weighttransferring move while the bike is still straight up and down, before entering the turn itself. If you make a sudden move, (like sticking out your knee), when you’re already in the turn, the bike may move off line, change direction slightly, ground out as the suspension loading is altered, or otherwise upset your plans and concentration.

Once comfortable with the knee out, try sliding your butt toward the inside edge of the seat, along with sticking out your knee. Try sliding more and more of your body off in stages, and lean your head and upper body inside as well.

You’ll have reached the limits of hanging off—and of cornering speed—when your butt is completely off the inside edge of the seat and your knee— along with whatever it is on the bike that drags—is skimming the pavement around the turn. Obviously, anybody hanging off enough to drag his knee should be wearing leather pants. If the leather wears through, duct tape makes a nice patch, and several layers of duct tape over the knee can prevent the leather from wearing through in the first place. Racers who drag knees routinely often have extra pieces of leather stuck to the knees of their racing suits, held in place by Velcro fasteners and several layers of duct tape.

A race track is also the only place you should need to hang off. Going around corners in town with everything dragging and your knee scraping only proves how foolish you are, not how brave.

When peak mid-turn speed is reached, it’s time to work on getting into and out of the turn harder (or faster). It’s best to start out using the brakes while you’re still upright, before turning. As you get used to riding fast and hanging off, and after you can spot and correct tire sliding, try braking later and harder before the turn. Work up to actually braking as you turn into the apex, getting off the brakes at the apex and rolling on the throttle for a fast exit. Try it in steps and be very careful. Note how the bike feels and reacts under the brakes. Applying the brakes while turning usually makes a bike straighten up, out of the lean, so the rider must hold the bike down in the lean, and be prepared for the bike to fall inward when he releases the brakes. Releasing the brakes smoothly, evenly, progressively is the key to making the transition from brakes to throttle at the apex, just as applying the brakes smoothly, evenly and progressively is the key to a fast entrance to the turn.

Some bikes have rear brakes that lock easily at turn entrances, complicating control. The rider must try to use the rear brake just hard enough to help slow the bike without locking the rear tire, and to rely mostly on the front brake. If a bike’s rear brake is so touchy it cannot be controlled, the rider should either modify it (removing pad or shoe material in steps, using a file, until it is controllable) or not use it.

When you’ve mastered all the parts of cornering, the trick is to tie all the movements and all the corners together smoothly, evenly. A good rider on a fast lap is smooth, the transition from upright to leaned to upright again made into one graceful movement instead of three jerky movements in quick succession.

Smoothness is control, and control is safety at any speed.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsUp Front

November 1981 By Allan Girdler -

Letters

LettersLetters

November 1981 -

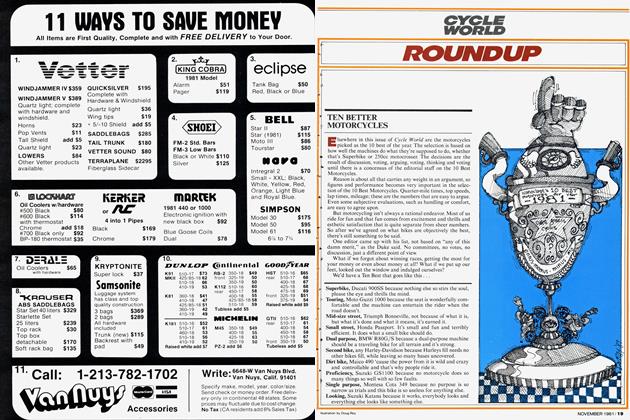

Departments

DepartmentsCycle World Roundup

November 1981 -

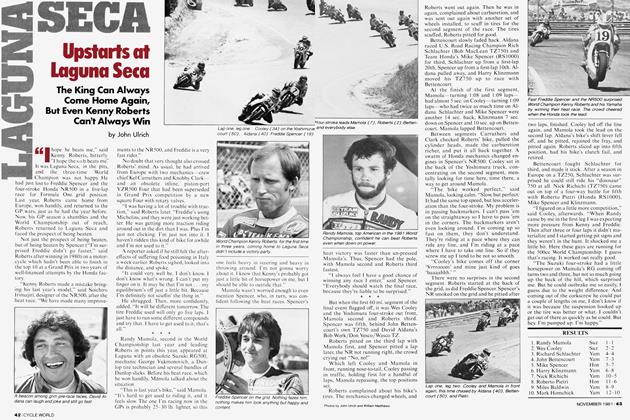

Laguna Seca

Laguna SecaUpstarts At Laguna Seca

November 1981 By John Ulrich -

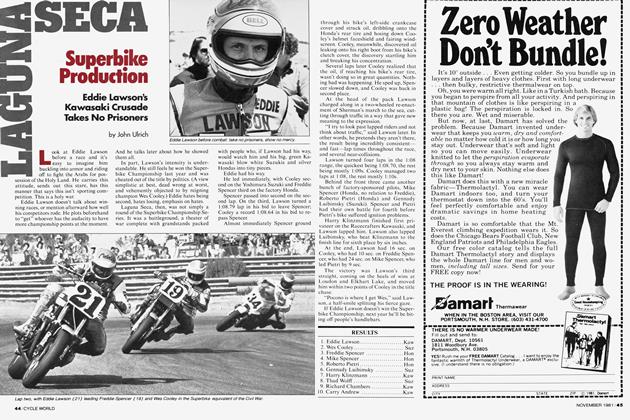

Superbike Production

November 1981 By John Ulrich -

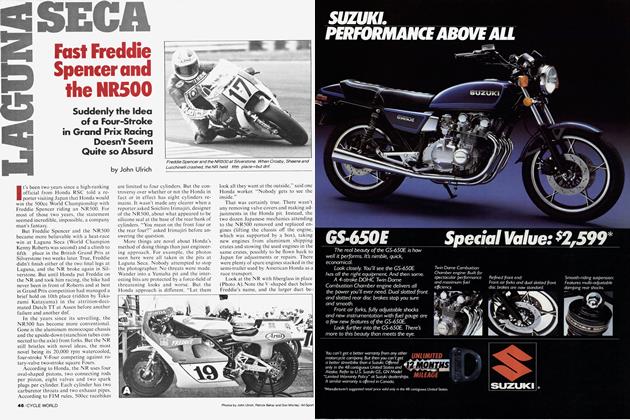

Fast Freddie Spencer And the Nr500

November 1981 By John Ulrich