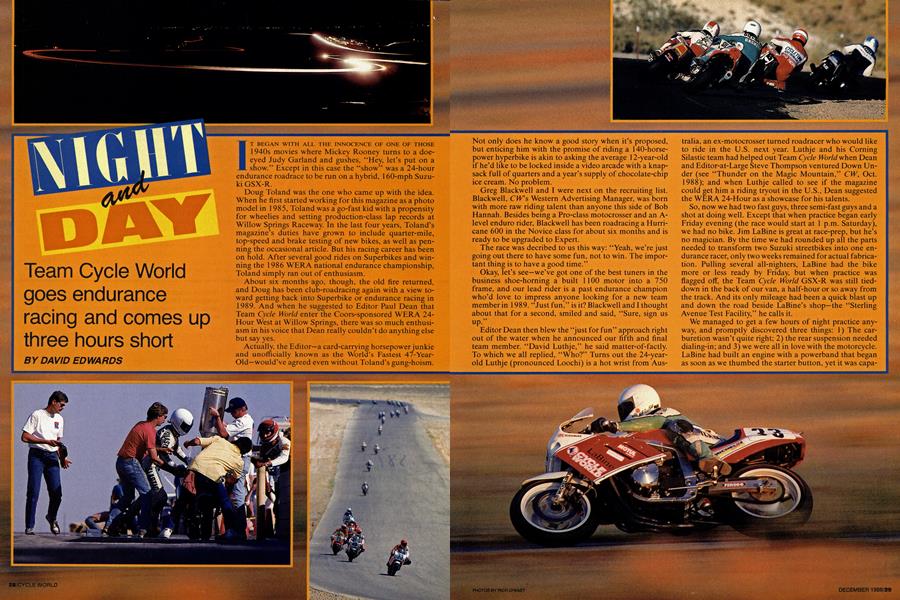

NIGHT and DAY

Team Cycle World goes endurance racing and comes up three hours short

DAVID EDWARDS

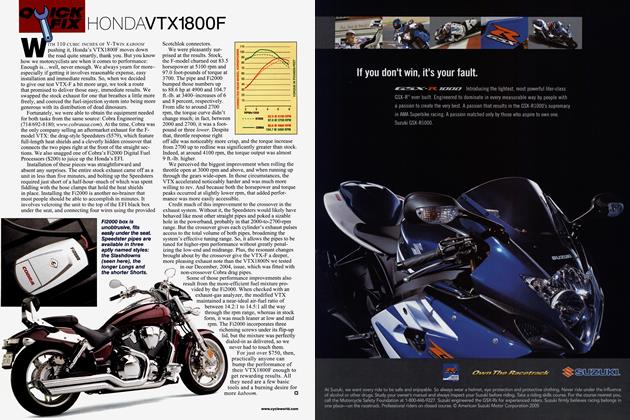

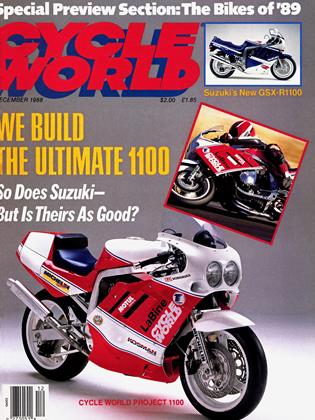

IT BEGAN WITH ALL THE INNOCENCE OF ONE OF THOSE 1940s movies where Mickey Rooney turns to a doeeyed Judy Garland and gushes, "Hey, let's put on a show." Except in this case the "show" was a 24-hour endurance roadrace to be run on a hybrid, 160-mph Suzuki GSX-R.

Doug Toland was the one who came up with the idea. When he first started working for this magazine as a photo model in 1985, Toland was a go-fast kid with a propensity for wheelies and setting production-class lap records at Willow Springs Raceway. In the last four years, Toland’s magazine’s duties have grown to include quarter-mile, top-speed and brake testing of new bikes, as well as penning the occasional article. But his racing career has been on hold. After several good rides on Superbikes and winning the 1986 WERA national endurance championship, Toland simply ran out of enthusiasm.

About six months ago, though, the old fire returned, and Doug has been club-roadracing again with a view toward getting back into Superbike or endurance racing in 1989. And when he suggested to Editor Paul Dean that Team Cycle World enter the Coors-sponsored WERA 24Hour West at Willow Springs, there was so much enthusiasm in his voice that Dean really couldn’t do anything else but say yes.

Actually, the Editor—a card-carrying horsepower junkie and unofficially known as the World’s Fastest 47-YearOld—would’ve agreed even without Toland’s gung-hoism. Not only does he know a good story when it’s proposed, but enticing him with the promise of riding a 140-horsepower hyperbike is akin to asking the average 12-year-old if he’d like to be locked inside a video arcade with a knapsack full of quarters and a year’s supply of chocolate-chip ice cream. No problem.

Greg Blackwell and I were next on the recruiting list. Blackwell, CtVs Western Advertising Manager, was born with more raw riding talent than anyone this side of Bob Hannah. Besides being a Pro-class motocrosser and an Alevel enduro rider, Blackwell has been roadracing a Hurricane 600 in the Novice class for about six months and is ready to be upgraded to Expert.

The race was decribed to us this way: “Yeah, we’re just going out there to have some fun, not to win. The important thing is to have a good time.”

Okay, let’s see—we’ve got one of the best tuners in the business shoe-horning a built 1100 motor into a 750 frame, and our lead rider is a past endurance champion who’d love to impress anyone looking for a new team member in 1989. “Just fun,” is it? Blackwell and I thought about that for a second, smiled and said, “Sure, sign us up.”

Editor Dean then blew the “just for fun” approach right out of the water when he announced our fifth and final team member. “David Luthje,” he said matter-of-factly. To which we all replied, “Who?” Turns out the 24-yearold Luthje (pronounced Loochi) is a hot wrist from Aus-

tralia, an ex-motocrosser turned roadracer who would like to ride in the U.S. next year. Luthje and his Corning Silastic team had helped out Team Cycle World when Dean and Editor-at-Large Steve Thompson ventured Down Under (see “Thunder on the Magic Mountain,” CW, Oct. 1988); and when Luthje called to see if the magazine could get him a riding tryout in the U.S., Dean suggested the WERA 24-Hour as a showcase for his talents.

So, now we had two fast guys, three semi-fast guys and a shot at doing well. Except that when practice began early Friday evening (the race would start at 1 p.m. Saturday), we had no bike. Jim LaBine is great at race-prep, but he’s no magician. By the time we had rounded up all the parts needed to transform two Suzuki streetbikes into one endurance racer, only two weeks remained for actual fabrication. Pulling several all-nighters, LaBine had the bike more or less ready by Friday, but when practice was flagged off, the Team Cycle World GSX-R was still tieddown in the back of our van, a half-hour or so away from the track. And its only mileage had been a quick blast up and down the road beside LaBine’s shop—the “Sterling Avenue Test Facility,” he calls it.

We managed to get a few hours of night practice anyway, and promptly discovered three things: 1) The carburetion wasn’t quite right; 2) the rear suspension needed dialing-in; and 3) we were all in love with the motorcycle. LaBine had built an engine with a powerband that began as soon as we thumbed the starter button, yet it was capable of running down anything else on the track. The brakes were wonderful to use and the experimental Ferodo pads showed almost no wear (LaBine later estimated that we could have gone the entire race with just one change of pads). Ground clearance was no problem whatsoever, the Michelin slicks had more stick than superglue, and the sound trailing out of the custom-built muffler was so, so sweet. Luthje pulled his helmet off after his practice stint and grinned, “She’s a beauty.”

NIGHT and DAY

During the morning practice session, the carburetion got fixed and the rear suspension came closer to being right. But as the bike was pushed to the grid, it still wasn’t as sorted out as LaBine would have liked. “I wish we had one more week,” he said.

With another week, we might also have been able to get our support crew better organized. A 24-hour race is a logistical nightmare, calling not only for multiple riders, but five people who have to man the pits around the clock, ready to refuel the bike every hour or so, and to make emergency repairs. And then there are the scorers each team must provide for the entire race, to record each lap their bike makes. You’ve also got to have food and drink for all these people, and provide a place for them to take naps. The list goes on and on.

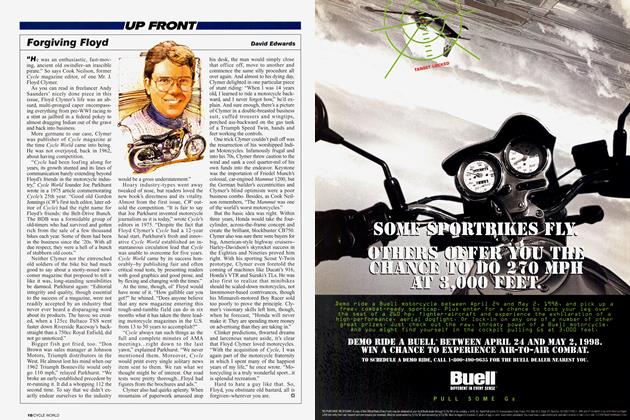

For the Willow 24-Hour, Cycle Worlds motley but enthusiastic crew of wives, girlfriends, co-workers and buddies ran to about 15 people; and while they all did yeoman service, we didn’t compare to some of the other teams. The Vance & Hines team, for example, showed up with 32 people resplendent in team uniforms, a custom-painted trailer, tents, air hoses and enough pit lights to illuminate the Statue of Liberty. We, on the other hand, worked out of a 100,000-mile box van, with pit lights jury-rigged on banged-together two-by-fours and powered by a 20-yearold Honda generator. And even that setup didn’t get built until someone noticed that the sun was going down.

Of course, one of the reasons we weren’t paying any attention to our pit lights was that—hastily built bike, rustic pits and inexperienced crew notwithstanding—we were leading the race. Toland had started for us, and by the fourth lap had simply driven around the the other teams to put the Cycle World bike up front, and was pulling away.

Our first scare came about an hour later when Luthje tried to pass a lapped rider and got into a horrific nearhighside that had him clambering all over the bike while running off the track. He got back on the asphalt with a shortness of breath, wide eyes, a bashed toe and a newfound faith in divine intervention; the bike was unscathed except for a steering damper that had come adrift. A lap later, WERA officials brought the race to a temporary halt when the Team Hammer Suzuki crashed spectacularly in the oil dropped by another bike. Fortunately, rider Jamie James came out of the 140-mph endo with only bruises and cuts, but Team Hammer, four-time WERA endurance champion, was through for the day. We used the redflag period to get Luthje’s breathing back to normal and to fix the steering damper, then sent him back into the fray on the restart.

At the six-hour mark, we were still in the lead, having a four-lap advantage at one point. But another problem soon surfaced: The bracket securing the exhaust pipe to the footpeg mount broke, allowing the pipe to flop about. A quick couple of turns of safety wire had the bike back in action again; and on the next scheduled pit stop, a hose clamp made for a more-permanent fix.

But not permanent enough; two hours later the clamp broke. So, this time, two hose clamps were used, and we had no more problems with the pipe. But we did have a problem with the rear shock—or rather, the hose for the remote hydraulic preload adjuster, which snapped off, locking the spring on its softest setting. The preload couldn’t be changed when Dean or Blackwell, both of whom weigh about 200 pounds, got on board, resulting in some wallowing while they were on the track. But the rest of the bike was holding up well, and the engine sounded just as strong as when it rolled out of LaBine’s shop. As the race droned into its 13th hour, we still had the lead, but our minor problems had allowed other teams to close up.

From there, things got a little foggy, both literally and figuratively, as the bikes swept around the blacknessshrouded, 2.5-mile track, pulled along by their headlight beams. Toland and Luthje did most of our night riding, spelled by Blackwell, while Paul and I decided that perhaps our night vision wasn’t quite good enough to be punching 150-mph holes through the desert night. Luthje was impressive, considering he’d seen Willow Springs for the first time just a day before and had never raced at night, but Toland was absolutely stunning during his night stints. Closing on some of the slower bikes with more than 50 mph in hand, he slashed his way around the track, passing on the inside, on the outside, wheelieing here and sliding there. One of the other teams’ members, himself an excellent night rider, wandered up to our pits after his session on the track and said, “You guys should just clone Toland and go get some sleep.”

We were out in front as the clock crept towards 6 a.m., but not for long, as the drive chain parted company with the bike in Turn 2. We never did recover the chain, so it’s impossible to pinpoint the cause, but it seems likely that the master link separated or a rock or piece of debris derailed the chain. In any case, a half-hour passed before the bike was back in the race, dropping us to fourth place.

Dean and I each rode a couple of sessions while Toland and Luthje got some sleep. Our only hope of winning now rested on the ability of those two to burn up the track and catch the Vance & Hines team, which had survived an early-race crash to steadily move up into first place.

Luthje scorched out of the pits and had just slipped into third some 10 minutes into his stint when one of a roadracer’s worst fears came true. Barrelling into Turn 1 at more than 150 miles an hour, Luthje sat up, grabbed the front brake and was rewarded with a lever that came in all the way to the handlebar. Another quick, futile pump or two was all he got before going straight off the track. Feathering the back brake, he had slowed down very little by the time a deep drainage ditch came zooming into view.

The last thing he remembers was trying to jump the ditch and then being flung off to the side as the bike self-destructed upon impact.

Semi-conscious and strapped to a backboard in the rear of an ambulance, Luthje was transported to a local hospital, where he was diagnosed as having a bad case of the bumps and bruises, and, luckily, just a minor fracture of the wrist. He was back at the track before the Vance & Hines team took the checkered flag at the 24th hour. Tough, those Aussies.

The Suzuki was in worse shape. Pruned of its fairing and front-brake master cylinder, and with a caved-in exhaust pipe and crunched tail section, the Cycle World GSX-R was parked for good with three hours left in the race. The brake failure was later traced to the left-front brake caliper’s quick-detach pin, which had fallen out and allowed the caliper to swing free.

The disappointment didn’t really set in until the next day. After all, in the space of about two weeks we’d built a bike and put together a team that almost was victorious in one of the premier events in American endurance racing.

But even without the win, we had learned a few things. One was that dropping a bigger engine into an ’88 GSXR750 frame makes for one very fast, very competent endurance racer. If Suzuki’s 1989 GSX-R 1100 is anything like our bike, fans of big sportbikes are in for a rare treat next year.

Second, Dean, Blackwell and I are pretty good riders, but the credit for our bike’s terrific showing clearly belongs on the talented shoulders of Jim LaBine, Doug Toland and David Luthje. Anyone interested in fielding an endurance team next year ought to put this trio on the payroll and then dust off a spot on the mantle for the championship trophy. These guys are that good.

And finally, while our eventual placing—21st overall, seventh in class—doesn’t compare to a victory, it’s still something to be proud of. As David Luthje said as he swigged down a beer after the race, “Well, we may not have won, but they damn sure knew that Team Cycle World was here.” ®

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Editorial

EditorialAdios, Specialization

December 1988 By Paul Dean -

At Large

At LargeEngineers

December 1988 By Steven L. Thompson -

Learnings

LearningsThe Buck-A-Day, 25-Year Habit

December 1988 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

December 1988 -

Roundup

RoundupWhither the Passenger?

December 1988 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupLetter From Europe

December 1988 By Alan Cathcart