THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO FRANK COOPER

A Few Words, More Or Less, From California's "Mr.Motorcycling," Who Is An Absolute Uncut Gem Of A Man.

FRANK COOPER is a onetrack verbal railroad full of “ands.” Nothing can stop him for long. He has been dumped by some of the biggest names in motorcycle manufacturing. But the “and”, not only part of his speech, but a basic part of his life, has always managed to carry him through.

He is a bull, standing before the goading red cape of motorcycling, unable to leave the arena, helpless to do anything but follow it bravely according to his instincts.

By his own admission he is a promoter. If there were no motorcycles, he would be just as happy selling washing machines. From his crew of happy washing machine customers, and from his sponsored washers, he would glean fascinating facts about washing machine behavior to take back to the factory for improvements. He would figure a way to promote washing machine races in the desert, so he could generate more interest and sell more machines. As this would look strange to most people, it’s a good thing he deals in motorcycles.

Come to think of it, motorcycling looked strange to a lot of people back when Cooper got into it. He belongs to the California motorcycling scene, as it belongs, and owes much of its structure, to him. He helped organize one of the first scrambles—and it may even be the very first-ever held in -> the United States. It was at Crater Camp, and he still remembers the path the bulldozer took to cut the course. He haggled with P.K. Wrigley, the Avalon townspeople, and the whole membership of District 37 to get a date set for the first fabulous Catalina Grand Prix. One year, he told AMA Secretary E.C. Smith to get Walter Davidson out of bed in the middle of the night when the AMA was late to sanction the island race; this was back when Harley-Davidson REALLY dominated the AMA. The hardy group who ride the California deserts owe to him the creation of the wide, flat “Cooper bar,” which Earl Flanders still sells under that name. Name a Southern California motorcycle dealer, any dealer who’s been around awhile, and Cooper will be able to say, “Oh, yeah, he used to race for me.’’ And, of course, the name Matchless would not command the respect it does in this hemisphere, had it not been for the fact that Cooper helped develop it into his self-proclaimed, but truly worthy, “King of the Desert.’’

HOW FRANK SHUCKED THE AMA

"When they were late with the sanction, we all [the district sports committee] got on the phone together to E.C. Smith. I told him, 'If we don't get the sanction from you, we'll get it from Sears-Roebuck. Go call Walter [Davidson] and get him out of bed and get his approval. The entry forms are going out tonight. But we want to let your Harley riders know whether they can ride legally or not.' "

MORE ON THE AMA

"I went back there representing the rider, not any make of machine. And this is the trouble with the AMA. Everybody has an axe to grind back there for their motorcycle. I went there, and Aub Lebard went there and Earl Flanders went there with the idea we were going to get things for our riders. And we did. We got the rules changed."

PLEASE EXPLAIN THE DEATH OF CATALINA IN 100 WORDS OR LESS

"I used to go around after the race and soft-soap the town people. I'd give the kids around town a penny for each beer can they picked up. Then go to a Chamber of Commerce meeting and see everybody was happy, and then the church, and then have a drink with the big wheels. I'd go down to the greenhouse and pay for all the trampled flowers in little old ladies' gardens, where bikes had crashed or spectators had been. The last year nobody did that. I was having an operation."

Cooper calls himself a “Florida-California native born in Chicago.’’ He rode motorcycles throughout his youth, starting when he was 14, and owned as many as three at a time. He was kind of a junior wheeler-dealer in bikes. Buy one, try it for awhile, get rid of it. But all this time, he never thought much about making money from motorcycles. They were simply there, just fun. He went on to college, took an engineering degree, and some time later ended up in Los Angeles, wheeling and dealing as usual—in meat slicers.

Bob Bates (the original version of Bates Industries) was next door and got Frank interested in making money from the motorcycle business. Cooper started out with the Powell scooter, getting the company to redesign it so that it would handle well and be easy to drive. He also had an automobile business going.

His first step in the motorcycle business proper was gigantic. He bought more than a hundred used Harleys, managing to keep it quiet until opening day on his showroom floor, when he unveiled a room full of newly painted, chromed and customized machinery. It came off with a bang. He sold close to half his stock that month and immediately became Southern California’s biggest retail dealer. WF" ensuing years, he retailed Indian (and was the biggest dealer in the USA), and distributed Matchless, AJS, Royal-Enfield, Francis-Barnett, Yamaha, Benelli and Parilia. Indian dumped him, using the excuse that he was handling Matchless. After he built the Matchless name over more than a decade, that company dumped him, using the excuse that he had taken on Yamaha in the lightweight category. After he spent two years sorting out the mechanical ennuies of the first Yamahas, Yamaha decided they wanted to handle their own distributing, and Cooper was again swept out the back door.

"The average guy, he's gonna buy a street machine... But he can't have any fun until he goes out and rides it in the rough stuff." ....M.

"Here's a machine that's been ridden in five runs, the guy's never even tightened a bolt on it, yet he's going out and ride a 100-mile race in the desert. Sure, you can say right now this is stupid. / know it's stupid. But they've got good money. Give 'em what they want."

"Are U.S. riders destructive? You bet they are. V\/e took 15 percent of Matchless' production of motorcycles. But we took 75 percent of their parts. That's how Americans tear up equipment. "

"You can't do things yourself, sometimes. But I found you can do an awful lot by needling others.”

"If you shout loud, you're gonna get something done!"

"I've spent an awful lot of time, perhaps more than I should've— because I sacrificed my business a lot—in trying to promote all this racing back in the forties and fifties.”

"I like sailing. I've got a catamaran, I've got a cruiser, too. I used to race speedboats. You have to break away from the thing you're in business with. I've always liked something that goes fast."

"I don't mind copying. The Japanese copy, we copy. If anybody's got anything good, let's admit they've got something better than us and let's use it."

A Capsule History of Matchless

"They were cooperative while old man Collier was alive. Collier died about 1954 or 1955. Then they had a new regime. Jock West got in there and he wouldn't listen to anybody. And the problems started. I ordered motorcycles per certain specifications, and, when they would get 'em here, usually late, they weren't to specifications at all. Sometimes they would send last year's models, with the date stamped right along with the engine number. Then they decided they could make good over here without me. So they cancelled me out. They bought out Indian and in three years they went down the tubes.',*

Frank Cooper, The Engineer

"You can use all the engineering books, you can use all the theory, but in the end there's only one way. That's try and try and try. "

How "Papa" Frank Scalped The Indian

"In 1946, we were the biggest Indian dealer in the U.S. But the distributor, Hap Alzina, didn't like the fact I had Matchless. So he took Indian away from us. So I killed off Indian in L.A. by taking them in trade on Matchless for $350 and selling them for $395. Boy, you couldn't give away a new Indian!"

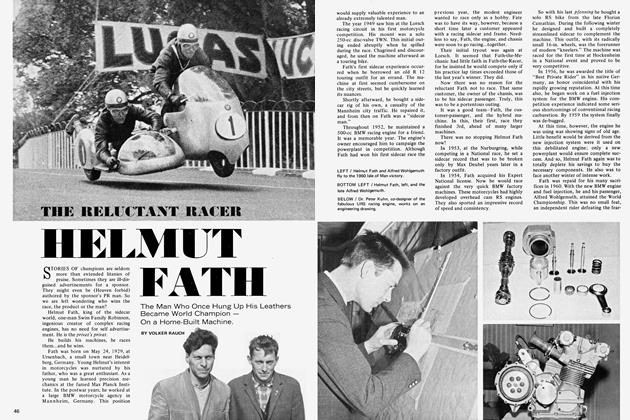

His time with Matchless is the most glittering part of his history. When he took on the distributorship, Triumph and Harley had the street bike market sewed up. “It was kind of hard to sell a big Single for the street, so I decided to concentrate on the dirt riding market.”

At the time there were only an odd half dozen big dirt events in Southern California. Obviously, if Frank was to make a living selling Matchless, he would have to go out and promote the sport. So he sponsored riders in desert races. At his peak, he had more than a score of sponsored riders on Matchless, and the bike dominated desert competition.

He first put Matchless’ name on the map with Dutch Sterner, who won the Big Bear run for him in 1946. He rarely paid his riders, who raced for fun and trophies and fondly called him “Papa.” His “wrecking crew” brought back suggestions to improve the Matchless, and he had the factory execute them.

To increase his market, he sent his boys out to the motorcycle clubs to show them how to put on races. He sent Bud Ekins and Vern Hancock to Europe to get a taste of international scrambling, and both returned much improved riders. Founding of the wellknown Rams Motorcycle Club was his doing, and they used to meet in a ramshackle school bus behind his shop. During these years, he put a great deal of energy into fostering the growth of the District 37 sports committee into an effective instrument that could put on a 12,000-spectator race on Catalina Island and demand grudging respect from the AMA in Columbus.

THE SPORT AS HE SEES IT

Flat track races: “I could care less about them. You watch the start. Then you go get a beer, sit around and talk and don’t even watch the race and come back and who’s doing what? Nobody knows. Just like Indianapolis. You’ve seen a couple of laps, you’ve seen it all.”

Road racing at Daytona: ‘‘It’s a good race for its type. But, personally, that kind of racing doesn’t interest me, because it’s just speed and speed’s only relative anyway.”

Motocross: “I think motocross is going to be THE thing in this country. It’s more interesting to the public. They see motorcycles flying into the air instead of just going around the same corner all the time. All they do in flat track is go around this corner, go around that corner. The only thing good about flat track is that you have a lot of starts.”

The proliferation of small bike classes in California Sportsman racing was largely due to his need to sell a batch of 200-cc FrancisBarnetts that had come to him from England. Nobody was interested in small bikes at the time, so Frank donated a set of gigantic trophies to be awarded winners of a new small bike category. Riders ride to win trophies, so he soon sold« his Fanny-Bees.

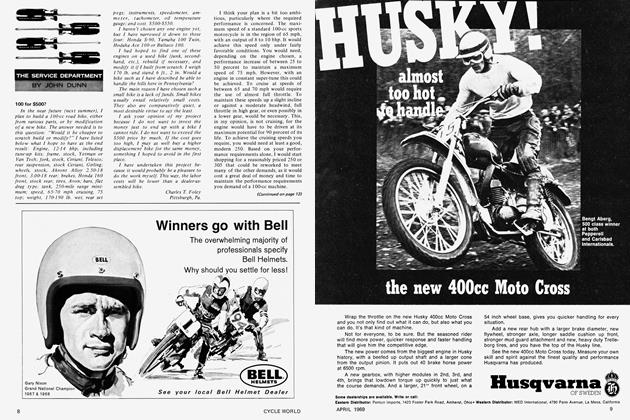

Nowadays, Cooper Motors is handling the Maico, an excellent motocross machine from West Germany. It is ideally suited to the American rider, and it got that way because he elicited full cooperation from the factory in making the necessary improvements. One of his first moves when he signed on with Maico was to bring a factory engineer to California to see the appalling conditions under which Americans race—dust, minimal maintenance, mile after mile of desert (“That’s why Maicos have a soft seat, unlike most motocross machines.”), and extremely high speeds, even on a motocross course. His latest move to publicize Maico was to bring West German champion Adolf Weil over to ride in the recent Inter-Am motocross series. It cost him more than $2500.

Naturally, Frank is doing his darndest to promote motocross, because that’s the kind of machine he’s selling now. The “Big M” used to stand for Matchless, but now those familiar wings are beginning to sprout on the M in Maico.

Cooper feels that the key to building the industry is to cater to the sportsman rider. “How is industry going to thrive, catering to the professional?” he says. “I’m interested in catering to the average rider, who wants to buy a motorcycle and have fun on it.” He looks after the participant, not the spectator. Participants want to win trophies. Donate lots of trophies, and riders will buy lots of motorcycles to go out and win them. It is a good philosophy and it works for him.

Some men could practice such a philosophy and it would be an expression of downright cynicism. In Frank Cooper’s case, it is a warm, unabashedly honest case of unbridled enthusiasm.